The “Marines’ Hymn” as it is known, extols the exploits of the Marines, and among these, is the invasion of Mexico in 1846, referred to in the first line of the Hymn with the phrase “From the Halls of Montezuma.”

The “Marines’ Hymn” as it is known, extols the exploits of the Marines, and among these, is the invasion of Mexico in 1846, referred to in the first line of the Hymn with the phrase “From the Halls of Montezuma.”

Forgotten, of course, are all the tales of rape, murder, and desecration of churches perpetrated by the Americans during their occupation of Mexico. These are not limited to the Marines, of course, but included both the regular army and the Texas Rangers, who have a long history of brutality toward Mexican Americans in Texas during and after the Mexican War.

But, just perusing the Army’s own web site on the history of the Mexican War, we find:

…Lane’s unit became most infamous for a brief engagement that followed an incident at Huamantla, a few miles from the town of Puebla, on 9 October 1847. When Captain Walker of the Texas Rangers fell mortally wounded in the skirmish, Lane ordered his men to “avenge the death of the gallant Walker.” Lt. William D. Wilkins reported that, in response, the troops pillaged liquor stores and quickly became drunk. “Old women and young girls were stripped of their clothes and many others suffered still greater outrages.” Lane’s troops murdered dozens of Mexicans, raped scores of women, and burned many homes…

…As the boredom of garrison duty began to set in, plundering, personal assaults, rape, and other crimes against Mexicans quickly multiplied. During the first month after the volunteers arrived, some twenty murders occurred.

Initially, Taylor seemed uninterested in devising diversions to occupy his men and failed to stop the attacks. As thefts, assaults, rapes, murders, and other crimes perpetrated by the volunteers mounted and Taylor failed to discipline his men, ordinary Mexican citizens began to have serious reservations about the American invasion. Taylor’s lackadaisical approach to discipline produced an effect utterly unanticipated by the Polk administration, many of whose members, particularly pro-expansionists such as Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker, believed that Mexicans would welcome the Americans as liberators. Instead, public opinion turned against the Americans and began to create a climate for guerrilla bands to form in the area. Mexicans from all social backgrounds took up arms. Some of them were trained soldiers; others were average citizens bent upon retaliating against the Americans because of attacks against family members.

Of course, there were instances of military infraction under Scott’s mandate. No violation under Scott’s orders, however, could be likened to the atrocious crimes committed under Zachary Taylor’s northern command. To be fair, it must be noted that there was no martial law in the regions of Mexico under Taylor’s earlier command. Commenting on Taylor’s initial occupation, Scott wrote to Secretary of War, William Marcy:

“Sir, our militia and volunteers [under Taylor], if a tenth of what is said be true, have committed atrocities – horrors – in Mexico, sufficient to make Heaven weep, and every American, of Christian morals, blush for his country. Murder, robbery – rape on mothers and daughters, in the presence of the tied up males of the families, have been common all along the Rio Grande. I was agonized with what I heard – not from Mexicans and regulars alone; but from respectable individual volunteers – from the masters and hands of our steamers.”

Much of the behavior was motivated by the crazed anti-Catholicism endemic among most American troops, and of course, by long-standing bigotry toward Mexicans in general. The disdain for civilian Mexicans was so great, in fact, that such behavior was a major motivating factor for the members of the famous San Patricio Battalion of Irish and German Catholics which went over the Mexican side at least partially in response to the American treatment of Mexican civilians. From a history of the San Patricios:

11:33 am on November 11, 2014Serving in the disputed Mexican territory, the Irish couldn’t believe the actions of the US military. In trying to initiate hostility, churches were desecrated, religious processions disrupted, and drunken soldiers who raped, pillaged, and burned Mexican villages and churches were only sent home. Riley and his fellow Irish emigrants began to question their decision to fight for men like these – especially in view of the anti-Catholic statements being made in the American Press to justify a war with Mexico. Mexican leaders knew that a large number of Catholic immigrants were in the U.S. Army and they sent flyers to them explaining the injustice of the cause they’d been duped into supporting. They asked for help to defend the simple Catholic farmers who were being attacked for their land. The story was familiar to the Irish; it was the Penal times all over again. The Irish, who were driven from their land under the same conditions, felt a solidarity with the Mexicans. The Mexican government promised Mexican citizenship and land to all who helped. Riley and his comrades didn’t have to think long. They stole across the river and joined the Mexicans to fight for what they believed was the right cause. Riley and his men were sent to help defend Monterey.

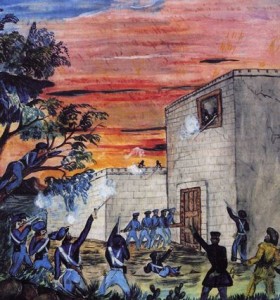

They demonstrated enormous courage at Buena Vista before the American Army, under General Stonewall Jackson, forced them back. The San Patricios were acclaimed as one of Mexico’s most fearless units. Fortified by more Irish and Germans who had left the American side, they were assigned to defend the Catholic convent of Churubusco against the onslaught of Gen Winfield Scott. During the battle, the Mexican’s [sic] tried to surrender, but each time Riley and his men pulled the white flag down. They would not surrender a convent to the men whom they had seen rape and plunder Mexican villages and churches.