For reasons that should become obvious, the essay that follows is not intended to express the smallest particle of disrespect for the two people who figure most prominently therein.

“While it’s true that God commands us ‘Thou shalt not kill,'” explained the grandmother in a gentle, solicitous tone, “you are permitted to kill in order to protect your family. Or if you’re made a soldier, and you’re ordered to kill, then you’re allowed to kill on behalf of your country.”

If you’re "made" a soldier? I mused to myself. That’s an interesting choice of verb.

The evening had been an unalloyed pleasure up until this point. We had been invited to spend some time with my parents, who own a small farm in eastern Oregon.

After a typically wonderful dinner of stir-fried vegetables taken just hours earlier from their garden, followed by deep-dish apple pie, Mom and Dad invited us to raid their strawberry and raspberry patches, and keep the fruit we plundered for our own use.

Following an hour or so spent gathering berries under a still-potent early evening Sun, we returned to the house and gathered in the living room to listen to my father expound the Ten Commandments. The discussion went well until we broached the subject of the troublesome Sixth Commandment.

My mother and father are the most honorable people I’ll ever meet, and are astonishingly unselfish. Being without guile, they are also entirely transparent when trying to make a point through means they consider subtle.

They are quite aware of the fact that Korrin and I are unalterably opposed to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the prospective war with Iran, and a return to conscription. And they are just as determined to exploit — or create — opportunities to counteract our efforts to raise children who properly revile the criminal organism called the State.

I am quite confident that the political fault-line separating Korrin and myself from our parents runs through countless other American families as well.

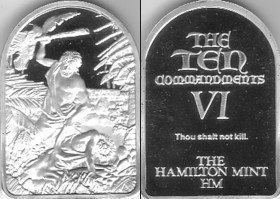

Real money, real law: The Sixth Commandment of God’s law, inscribed on a silver ingot; the State’s ethical view is illustrated on the reverse by a depiction of Cain murdering his innocent brother, Abel.

Real money, real law: The Sixth Commandment of God’s law, inscribed on a silver ingot; the State’s ethical view is illustrated on the reverse by a depiction of Cain murdering his innocent brother, Abel.

After mother had insisted that there is a secret “you may kill for your government” codicil to the Sixth Commandment, I inserted myself into the conversation as gently as I could.

“What I’ve taught the kids,” I said in a conversational tone, “is that the only time God permits us to kill would be a circumstance in which refusing to kill might result in the death of an innocent person for whom we have legitimate responsibility. In a case of that kind, I’m actually required to kill. For instance, if someone directly threatened my family, I would not only be allowed to kill the assailant, but actually would bear the bloodguilt of my family if I didn’t use lethal force to defend them.”

Mom and Dad nodded distractedly, but it was obvious that my clarification didn’t sit well with them. After all, the principle I adumbrated would mean that Iraqis are morally entitled to kill American soldiers who break into their homes and threaten their families.

We discussed the Decalogue for a few more minutes, and then the younger children peeled off in pursuit of other distractions. Only ten-year-old William and nine-year-old Isaiah were left in the room when I posed the following question: “To whom do the Ten Commandments apply?”

“They apply to everyone,” William happily replied, as my Dad nodded in guarded approval, sensing that the lesson was moving in a direction he didn’t entirely like. His unease was not relieved by my next question: “Do they apply to the government?”

A puzzled silence thrust itself on the room, occupying it for a moment or two until William and Isaiah both chimed in.

“Yes, but the government doesn’t obey them,” William said, as Isaiah eagerly over-talked his brother with essentially the same answer. By this time, my father’s frown was nearly audible.

“So — if government orders you to disobey any of the Ten Commandments, do you obey the government?” I continued.

“Yes,” Dad quickly interjected, his face radiating weary disapproval.

“No, we don’t,” replied William and Isaiah, in unison.

“If the government orders you to disobey God’s law, do you obey God or the government?” I persisted.

“You obey God,” my children answered.

“You obey your government,” Dad quietly insisted, out of duty rather than conviction. The conversation then uncomfortably trickled away, replaced by a polite silence that was drawn taut by the effort to avoid an overt argument.

It wasn’t my intention to act like a prosecutor or a garden-variety smart-ass. But my father — the greatest and most decent man I will ever know — had put me in an untenable position: I could either politely defer to my father as he offered instruction in unalloyed idolatry, or offend my parents by quietly contradicting the obvious point of the exercise — namely, that in a conflict between God’s law and the State’s commandments, we’re to obey the latter.

The point of a conversation is often the issue that thrusts itself out in sharp relief from the rest of the dialogue.

In reviewing the Ten Commandments, my Mom and Dad — who are, I hasten to observe, just like countless other decent people in this respect — saw fit to qualify only one of them, the commandment against murder.

They didn’t specifically tell my children that it is acceptable to lie, steal, covet, dishonor one’s parents, or commit adultery if the government requires such conduct of them. They did, however, take special care to emphasize that the government can order them to kill other human beings who have done them no harm, in direct contradiction of God’s unqualified commandment not to murder. Of course, if government can make a nullity of that commandment, it can revise the others to suit its purposes as well.

Indeed, government — particularly the despicable state that rules us — is little more than a perpetual organized assault on the Ten Commandments. The defining act of a government is extracting wealth from people through the threat of lethal violence, and swaddling such acts in invidious rhetoric about “social justice.” Thus at its very foundation, the State institutionalizes violations of the commandments against theft, murder, and covetousness.

The State’s fundamental function — killing, or the threat to do so — is intimately connected to a claim of ownership over its subjects. This is revealed in ways both vulgar and oblique. The best example of the former is the practice of conscription. Any government that can “make” an individual a soldier against his will is one richly deserving to be overthrown. A milder version of the same presumption can be seen every time a politician in a storm-threatened community issues a “mandatory evacuation” order to its residents, as if their lives were his, rather than theirs.

Government deprived of its power of discretionary violence, it is often said, wouldn’t be much of a government at all. This, we are told by puzzled and outraged people, would be a problem of some sort. While governments run by hypocritical people who invoke God’s law have done a great deal of harm, it wasn’t until Machiavelli and others of like mind elevated the State above that law — beginning with the commandment against murder — that it became the engine of murder and misery with which we’re so familiar.

Of course, owing to human nature we’re stuck with government of some variety, even though there’s ample reason to believe that our existing regime is quickly headed for abject bankruptcy and a Soviet-style collapse. But that doesn’t mean we are required to venerate or even respect the people who operate the organs of official extortion.

Of course, owing to human nature we’re stuck with government of some variety, even though there’s ample reason to believe that our existing regime is quickly headed for abject bankruptcy and a Soviet-style collapse. But that doesn’t mean we are required to venerate or even respect the people who operate the organs of official extortion.

Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Regime, Alexander Solzhenitsyn offered this admonition to those who wanted to bring about the end of that totalitarian state, with respect to the proper treatment to be given to agents of that state: “Don’t believe them, don’t fear them, don’t ask anything of them.”

In other words, treat them with politeness and respect, and ignore entirely the conceit that they are clothed in some peculiar sanctity that permits them to use or require the use of lethal violence to compel submission to their will. To behave otherwise is to act on premises that are essentially idolatrous.