In our perilous, chaotic times of Black Lives Matter and George Floyd, it is essential to know the deep background story of the history of Communist apparats/fronts and African-Americans, from the beginning of the Communist Party (and other Marxist-Leninist ideological instrumentalities) attempts to capture and engage the allegiance of Black Americans from 1919 to the present. Black Lives Matter, Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA)

Here are several items below to explore:

“ANARCHY U.S.A.” –– 1966 John Birch Society Film.

This is a C-SPAN 3 re-broadcast of an anti-communism film, produced in 1966 by the John Birch Society, which uses narration and news footage to detail the methods of communist revolutionaries in China, Algeria, and Cuba, then argues that U.S. Civil Rights leaders are also Communists using the same methods. The film condemns several U.S. Presidents and the 1964 Civil Rights and 1965 Voting Rights Acts.

The Communist Position on the Negro Question (pdf)

For decades this was the official statement of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA)

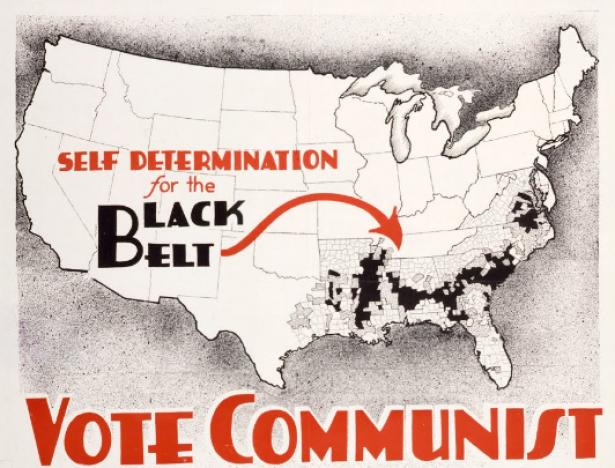

“Even as the Great Migration witnessed a major shift of African Americans from the rural South to Northern cities and urban centers, during the Depression decade the majority of blacks were still scratching out a meagre living as sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and migrant laborers tied by debt and KKK terrorism to peonage in the South. In the 1930s, the Communist Party U.S.A. dedicated itself to fighting the “defenders of white chauvinism,” educating and liberating oppressed African Americans, and advocating for “Self-Determination for the Black Belt.”

Here is the formal FBI analysis of this document.

Communist Revolution in the Streets, by Gary Allen

This seminal volume has been actively suppressed and surviving copies are extremely rare. Here are excerpts from this prophetic work — One, Two, Three, Four, Five, and Six

The Whole of Their Lives: Communism in America – A Personal History and Intimate Portrayal of Its Leaders, by Benjamin Gitlow

Gitlow was American Communist Party General Secretary, Communist International executive committee member who courageously revealed the true nature of subversion, infiltration & Stalinist control of the CPUSA.

I own a signed edition of this rare book.

The Red Decade: The Stalinist Penetration of America, by Eugene Lyons

Amazon Review:

As the author points out the “decade” of penetration by the communists in America never really ended. Those fanatical comrades wound up in places of influence and with each generation that influence has remained and become magnified. When you read this book you will recognize many tactics, ideas, and strategies that are visible today. This book should be read alongside the books by Diana West wherein she describes this country’s attack from within and how we have never really come to grips with nor denounced the communist takeover of our culture and society. That was a triumph of the reds: to operate in this country and to be able to simultaneously inoculate themselves from the blowback of condemnation. Much of what we are living with today, the political correctness and the rest of the insanity stems from the left’s desire to destroy from within.

Color, Communism And Common Sense, by Manning Johnson

This book by former Communist apparatchik Manning Johnson is a must read. As the current chaotic political environment swells, remnants of the past are ignored. This powerful book gives incredible insight into the tricks and the trade of the Communist Party, and their manipulation of minorities here in the USA. This been going on for a long period and the contemporary leaders of the BLM movement have claimed they are trained Marxists. In 1932, Johnson studied for three months under J. Peters, William Z. Foster, Jack Stachel, Alexander Bittelman, Max Bedacht, Israel Amter, Gil Green, Harry Haywood, and James S. Allen among others at the “National Training School,” part of the New Workers School, a “secret school” devoted to training “development of professional revolutionists, professional revolutionaries, or active functionaries of the Communist Party.” He served as a national organizer for the Trade Union Unity League. From 1931 to 1932, he served as a District agitation propaganda director for Buffalo, New York. From 1932 to 1934, he was district organizer for Buffalo. In 1935, Manning Johnson ran as a Communist Party candidate for New York’s 22nd Congressional District for the United States House of Representatives. From 1936 to 1939, he served on the Party’s National Committee, National Trade Union Commission, and Negro Commission. Fellow members of the Party’s National Negro Commission were: James S. Allen, Elizabeth Lawson, Robert Minor, and George Blake Charney. The infiltration of other parties started long before the Communist Control Act of 1954. Communists predominantly hide behind and operate under other party names, primarily the Democrats. They also do their work via many front organizations that indoctrinate, stir, and agitate their pawns.

In Hearings Regarding Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups: Hearings Before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-first Congress, First Session, Parts 1-3, Manning Johnson produced a list of Communist-front organizations that included: African Blood Brotherhood (headed by Richard B. Moore and Cyril Briggs), All Harlem Youth Conference, American Negro Labor Congress, Artists Committee for Protection of Negro Rights, Citizens Committee for the Appointment of a Negro to the Board of Education, Civil Rights Congress, Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service and Training, Committee for the Negro in the Arts, Committee to Abolish Peonage, Committee to Aid the Fighting South, Committee to Defend Angelo Herndon, League of Young Southerners, Council on African Affairs, Defense Committee for Claudia Jones, George Washington Carver School, Harlem Committee to End Police Brutality, Harlem Council on Education, International Committee of Negro Workers, International Committee on African Affairs, International Trade Union Committee for Negro Workers, International Workers Order, League for Protection of Minority Rights, League of Struggle for Negro Rights, National Conference of Negro Youth, National Emergency Committee to Stop Lynching, National Negro Congress, National Student Committee for Negro Problems, Negro Cultural Committee, Negro Labor Victory Committee, Negro People’s Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, Scottsboro Defense Committee, Southern Negro Youth Congress, Southern Youth Legislature, United Aid for Peoples of African Descent, United Front for Herndon, United Harlem Tenants and Consumers Organization, and United Negro and Allied Veterans of America among others.

Black and Conservative: The autobiography of George S. Schuyler, by George S. Schuyler

Don’t Believe the Hype!!: The Incredible History of Communist Subversion in America’s Black Community, by C Brian Madden

Amazon Book Description

Have you ever wondered why, today’s American culture has took a dramatic change for the worse? Have you ever wondered by our youth are no longer interested in pursuing the “American Dream” anymore? Ever wonder why, a certain culture of people, have no longer cared about whether they live or die or not, say “blank the police” and are always hostile towards those holding authority? The answer to these questions will shock you; and they are being done on purpose!! This book will show you how we got to this point in today’s society, especially when it comes to the African-American Community.

Black Revolutionaries in the United States: Communist Interventions, Volume II, by Communist Research Cluster

Blacks and Reds: Race and Class in Conflict, 1919-1990, by Earl Ofari Hutchinson

Amazon Book Description:

In this important study, Earl Ofari Hutchinson examines in detail the American Communist Party’s efforts to win the allegiance of black Americans and the various responses to this from the black community. Beginning with events of the 1920s, Hutchinson discusses at length the historical forces that encouraged alliances between African Americans and the predominately white American Communist Party. He also takes an in-depth look at why, and how, issues of class, party ideology, and racial identity stood in the way of a partnership of black leaders and communists in the United States. Blacks and Reds addresses landmark events surrounding associations between communists and black activists. Hutchinson examines, among other things, how Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois’s support of party activities affected their lives and how the Communist Party used the trial of Angela Davis to promote its own interests. His scope ranges from oft forgotten signs of misdirection, such as how communists’ efforts to express racial sympathy in the early 1950s contributed to their own near destruction during the McCarthy era, to a thorough discussion of how the Party’s effort to gain a foothold in Stokely Carmichael’s SNCC, Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, Martin Luther King’s SCLC, and Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Panthers shook up the civil rights movement by triggering the FBI’s secret war against King, Malcolm X, and others considered to be black radicals.

How Communists Became a Scapegoat for the Red Summer ‘Race Riots’ of 1919, article by Becky Little

Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Communist, by Harry Haywood

A Black Communist in the Freedom Struggle, by Harry Haywood

Amazon Book Description:

Mustering out of the U.S. army in 1919, Harry Haywood stepped into a battle that was to last the rest of his life. Within months, he found himself in the middle of one of the bloodiest race riots in U.S. history and realized that he’d been fighting the wrong war—the real enemy was right here at home. This book is Haywood’s eloquent account of coming of age as a black man in twentieth-century America and of his political awakening in the Communist Party.

For all its cultural and historical interest, Harry Haywood’s story is also noteworthy for its considerable narrative drama. The son of parents born into slavery, Haywood tells how he grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, found his first job as a shoeshine boy in Minneapolis, then went on to work as a waiter on trains and in restaurants in Chicago. After fighting in France during the war, he studied how to make revolutions in Moscow during the 1920s, led the Communist Party’s move into the Deep South in 1931, helped to organize the campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys, worked with the Sharecroppers’ Union, supported protests in Chicago against Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, fought with the International Brigades in Spain, served in the Merchant Marines during World War II, and continued to fight for the right of self-determination for the Afro-American nation in the United States until his death in 1985.

This new edition of his classic autobiography, Black Bolshevik, introduces American readers to the little-known story of a brilliant thinker, writer, and activist whose life encapsulates the struggle for freedom against all odds of the New Negro generation that came of age during and after World War I.

Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950, by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore

Amazon Review:

Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950 by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore redefines the standard chronology of the Civil Rights movement, popularly known for its post-WWII activity. Post-WWII civil rights action would culminate in achievement with Brown v. Board of Education and the 1964 and 1965 Acts of President Johnson. As the title of the book indicates, and according to Gilmore, civil rights in fact had far earlier and far more radical origins in Communism, labor, Fascism and anti-Fascism, and the Popular Front. She substantiates her thesis by tracing the activity of these movements, and by placing within them the African Americans and whites involved who both worked together and in opposition to one another to end or continue Jim Crow. The issue of black civil rights is typically isolated to the United States and is considered to be historically a distinct American problem. By highlighting the involvement of radical movements that found their roots in Europe, Gilmore places African American civil rights on an international stage and redefines it within the context of what the world was experiencing and how this weaved into American culture. Gilmore shows that in America there was an active Communist Party that was focused on illuminating how racism created class differences, and had a purpose to overcome this class inequality by organizing Southern black laborers into a force white supremacists could not reckon with. The CPUSA would become a major player in calling for an end to Jim Crow and white supremacy, and would operate at the same time of the NAACP, whom the communists considered too conservative and bourgeois. The distinction between the two is one where the Communist Party favored direct action and the NAACP preferred legal means to solve issues, and Gilmore states that when placed alongside Communism, the conservative nature of the NAACP is stark (7). In emphasizing this simplistic distinction between the two, Gilmore slights the NAACP of some of its own influence and early contribution. Though less radical in comparison to a system like Communism, the NAACP nevertheless operated within a legal system that was hostile to them. When placed within the cultural context of America in the early 20th century, the NAACP was also radical in its own way because it defied the “place” of the African American, and the organization enjoyed many successes of its own. For example, the NAACP played a major role in the 1923 Moore v. Dempsey decision that strengthened due process and African American’s Constitutional rights. It was not only the Communist Party that took an interest in labor either, though Gilmore makes it seem as if labor was a CPUSA concern only and does not mention that the NAACP was involved in the creation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first African American labor union (52). Though these successes are certainly not as radical as labor marches through the streets of Gastonia, they are still significant to early civil rights radicalism. In keeping with the international scope of civil rights and the importance of the Communist Party, Gilmore brings to light that Africa Americans even went to Russia, had audience with Stalin himself, and many even let out sighs of relief to be in a country where they could, for the first time, enjoy life without fear. African American civil rights and Communism are two movements not typically linked together. In placing them together, Gilmore effectively rewrites civil rights history to include world wide involvement. She does similarly with Fascism in the United States. Gilmore reveals that Fascist ideology was intertwined with white supremacy (106), yet Gilmore does not adequately make the connection between the ideologies of Fascism and white supremacy to explain how white supremacists co-opted Fascism into their beliefs. Additionally, Gilmore splits up the influence of Fascism into two different sections, one in which she describes how some Americans embraced it early on, and then how later Fascism became linked with Communism and Nazi policy, and was thereafter largely rejected within America. Gilmore skips from one to the other without describing the intermediate years and how white supremacists that were once Fascist came to reject the ideology. Gilmore makes it clear why they did, but does not trace how or what happened to the former Black Shirt white supremacist American Fascists. Gilmore focuses her narrative on select people and groups, which allows her to make her points without filling pages with names and events that would have made the monograph dense and less fluid. Through the experiences of her select characters, Gilmore documents the progress of movements and is then allowed to move on with her point made by their examples. As she admits in her introduction, she leaves out a significant portion of people in the South who played major roles in the Civil Rights movement (11). As reviewer Michael Dennis points out, the people ignored precisely the kind of political linkages that defined the popular front and did a good deal more grass roots organizing in the South than Fort-Whiteman. While leaving out these groups of people and their contributions does not weaken the argument Gilmore is trying to make, adding them would have strengthened her narrative by illustrating the scope of the work the Popular Front involved itself in. While she leaves out some groups and people, she includes other often overlooked players such as Truman’s committee on civil rights, adding another layer to the retelling of conventional civil rights history (409). Gilmore’s limited focus allows her to incorporate an element of familiarity that makes her story easier and more enjoyable to read. The people involved in the movements she writes about become more than just names, but people with personalities. The emotional connection forged with these people give the book a sense of intimacy. Much like in her previous book, Gender & Jim Crow, Gilmore uses this feeling of familiarity to make assumptions about people’s feelings and motivations that cannot be supported by evidence. For instance, Gilmore assumes that Louise Thompson must have been hiding something about her feelings for African American Communist Lovett Fort-Whiteman (143). She does the same when she attempts to psychoanalyze the reticence of Alain Locke and attributes it to an attraction to the charismatic Langston Hughes (137). These are things that Gilmore herself simply cannot know without personal testimony. In some cases, Gilmore is able to more successfully pull off her personal narratives. When she describes the death of Fort-Whiteman, she adds a touching reflection of his last moments that closes up the extraordinary life of this very unique man (154). It is in moments like those that Gilmore fosters a true emotional connection between her book and the reader. The combination of humanization and the personalization of events with a unique historical interpretation make Defying Dixie an essential book on the civil rights movement. Defying Dixie adds a new layer to the understanding of how the civil rights movement progressed, and what influenced the later movement. While it does not rewrite the entirety of the movement, it inserts a new level that should not be overlooked.

Red Chicago: American Communism at Its Grassroots, 1928-35, by Randi Storch

Amazon Book Description:

Red Chicago is a social history of American Communism set within the context of Chicago’s neighborhoods, industries, and radical traditions. Using local party records, oral histories, union records, party newspapers, and government documents, Randi Storch fills the gap between Leninist principles and the day-to-day activities of Chicago’s rank-and-file Communists.

Uncovering rich new evidence from Moscow’s former party archive, Storch argues that although the American Communist Party was an international organization strongly influenced by the Soviet Union, at the city level it was a more vibrant and flexible organization responsible to local needs and concerns. Thus, while working for a better welfare system, fairer unions, and racial equality, Chicago’s Communists created a movement that at times departed from international party leaders’ intentions. By focusing on the experience of Chicago’s Communists, who included a large working-class, African American, and ethnic population, this study reexamines party members’ actions as an integral part of the communities and industries in which they lived and worked.

Communists in Harlem During the Depression, by Mark Naison

Amazon Book Description:

No socialist organization has ever had a more profound effect on black life than the Communist Party did in Harlem during the Depression. Mark Naison describes how the party won the early endorsement of such people as Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and how its support of racial equality and integration impressed black intellectuals, including Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Paul Robeson.

This meticulously researched work, largely based on primary materials and interviews with leading black Communists from the 1930s, is the first to fully explore this provocative encounter between whites and blacks. It provides a detailed look at an exciting period of reform, as well as an intimate portrait of Harlem in the 1920s and 30s, at the high point of its influence and pride.

Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression, by Robin D. G. Kelley

Amazon Book Description:

A groundbreaking contribution to the history of the “long Civil Rights movement,” Hammer and Hoe tells the story of how, during the 1930s and 40s, Communists took on Alabama’s repressive, racist police state to fight for economic justice, civil and political rights, and racial equality.

The Alabama Communist Party was made up of working people without a Euro-American radical political tradition: devoutly religious and semiliterate black laborers and sharecroppers, and a handful of whites, including unemployed industrial workers, housewives, youth, and renegade liberals. In this book, Robin D. G. Kelley reveals how the experiences and identities of these people from Alabama’s farms, factories, mines, kitchens, and city streets shaped the Party’s tactics and unique political culture. The result was a remarkably resilient movement forged in a racist world that had little tolerance for radicals.

After discussing the book’s origins and impact in a new preface written for this twenty-fifth-anniversary edition, Kelley reflects on what a militantly antiracist, radical movement in the heart of Dixie might teach contemporary social movements confronting rampant inequality, police violence, mass incarceration, and neoliberalism.

How ‘Communism’ Brought Racial Equality To The South

National Public Radio (NPR Broadcast ) State-sponsored media interview:

Tell Me More continues its Black History Month series of conversations with a discussion about the role of the Communist Party. It was prominent in the fight for racial equality in the south, specifically Alabama, where segregation was most oppressive. Many courageous activists were communists. Host Michel Martin speaks with historian Robin Kelley about his book Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression about how the communist party tried to secure racial, economic, and political reforms.

Red, Black, White: The Alabama Communist Party, 1930–1950, by Mary Stanton

Amazon Book Description:

Red, Black, White is the first narrative history of the American communist movement in the South since Robin D. G. Kelley’s groundbreaking Hammer and Hoe and the first to explore its key figures and actions beyond the 1930s. Written from the perspective of the district 17 (CPUSA) Reds who worked primarily in Alabama, it acquaints a new generation with the impact of the Great Depression on postwar black and white, young and old, urban and rural Americans.

After the Scottsboro story broke on March 25, 1931, it was open season for old-fashioned lynchings, legal (courtroom) lynchings, and mob murder. In Alabama alone, twenty black men were known to have been murdered, and countless others, women included, were beaten, disabled, jailed, “disappeared,” or had their lives otherwise ruined between March 1931 and September 1935. In this collective biography, Mary Stanton―a noted chronicler of the left and of social justice movements in the South―explores the resources available to Depression-era Reds before the advent of the New Deal or the modern civil rights movement. What emerges from this narrative is a meaningful criterion by which to evaluate the Reds’ accomplishments.

Through seven cases of the CPUSA (district 17) activity in the South, Stanton covers tortured notions of loyalty and betrayal, the cult of white southern womanhood, Christianity in all its iterations, and the scapegoating of African Americans, Jews, and communists. Yet this still is a story of how these groups fought back, and fought together, for social justice and change in a fractured region.

Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, by Cedric Robinson

Amazon Book Description:

In this ambitious work, first published in 1983, Cedric Robinson demonstrates that efforts to understand Black people’s history of resistance solely through the prism of Marxist theory are incomplete and inaccurate. Marxist analyses tend to presuppose European models of history and experience that downplay the significance of Black people and Black communities as agents of change and resistance. Black radicalism, Robinson argues, must be linked to the traditions of Africa and the unique experiences of Blacks on Western continents, and any analyses of African American history need to acknowledge this.

To illustrate his argument, Robinson traces the emergence of Marxist ideology in Europe, the resistance by Blacks in historically oppressive environments, and the influence of both of these traditions on such important twentieth-century Black radical thinkers as W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, and Richard Wright. This revised and updated third edition includes a new preface by Tiffany Willoughby-Herard, and a new foreword by Robin D. G. Kelley.

Marxist-Leninist Perspectives on Black Liberation and Socialism, by Frank Chapman

Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism, by Erik S. McDuffie

Amazon Book Description:

Sojourning for Freedom portrays pioneering black women activists from the early twentieth century through the 1970s, focusing on their participation in the U.S. Communist Party (CPUSA) between 1919 and 1956. Erik S. McDuffie considers how women from diverse locales and backgrounds became radicalized, joined the CPUSA, and advocated a pathbreaking politics committed to black liberation, women’s rights, decolonization, economic justice, peace, and international solidarity. McDuffie explores the lives of black left feminists, including the bohemian world traveler Louise Thompson Patterson, who wrote about the “triple exploitation” of race, gender, and class; Esther Cooper Jackson, an Alabama-based civil rights activist who chronicled the experiences of black female domestic workers; and Claudia Jones, the Trinidad-born activist who emerged as one of the Communist Party’s leading theorists of black women’s exploitation. Drawing on more than forty oral histories collected from veteran black women radicals and their family members, McDuffie examines how these women negotiated race, gender, class, sexuality, and politics within the CPUSA. In Sojourning for Freedom, he depicts a community of radical black women activist intellectuals who helped to lay the foundation for a transnational modern black feminism.

Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones, by Carole Boyce Davies

Amazon Book Description:

In Left of Karl Marx, Carole Boyce Davies assesses the activism, writing, and legacy of Claudia Jones (1915–1964), a pioneering Afro-Caribbean radical intellectual, dedicated communist, and feminist. Jones is buried in London’s Highgate Cemetery, to the left of Karl Marx—a location that Boyce Davies finds fitting given how Jones expanded Marxism-Leninism to incorporate gender and race in her political critique and activism.

Claudia Cumberbatch Jones was born in Trinidad. In 1924, she moved to New York, where she lived for the next thirty years. She was active in the Communist Party from her early twenties onward. A talented writer and speaker, she traveled throughout the United States lecturing and organizing. In the early 1950s, she wrote a well-known column, “Half the World,” for the Daily Worker. As the U.S. government intensified its efforts to prosecute communists, Jones was arrested several times. She served nearly a year in a U.S. prison before being deported and given asylum by Great Britain in 1955. There she founded The West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News and the Caribbean Carnival, an annual London festival that continues today as the Notting Hill Carnival. Boyce Davies examines Jones’s thought and journalism, her political and community organizing, and poetry that the activist wrote while she was imprisoned. Looking at the contents of the FBI file on Jones, Boyce Davies contrasts Jones’s own narration of her life with the federal government’s. Left of Karl Marx establishes Jones as a significant figure within Caribbean intellectual traditions, black U.S. feminism, and the history of communism.

Black on Red: My 44 Years Inside the Soviet Union: An Autobiography, by Robert Robinson

John Alt Review:

Some years ago, I read Black On Red: My 44 Years Inside The Soviet Union, a book by Robert Robinson, An African-American who lived in Detroit during the Depression. I had to read it again, for it is about as gripping an autobiography as one can find. Hired in 1927 as a floor sweeper by Ford Motor Company, he became a toolmaker there. In April 1930, through Amtorg, a Soviet trade agency based in New York, a Russian delegation toured the plant. A Russian asked if he would like to work in the Soviet Union. At Ford he earned $140 a month–good wages–but was offered $250 a month, free living quarters, maid service, 30 days vacation a year and a car. All of this for a one year contract. At 23 and recently from Cuba, where he grew up, he was ready for some adventure. Like most things Soviet, the promises were eventually to mark a tragic life, his.

So in 1930 Robinson went, and thereon hangs his tale. He describes various discrimination against blacks while the Soviet government painted itself as an ethnically tolerant utopia.

Robert Robinson was a highly talented, even gifted toolmaker and mechanical engineer. (He graduated from The Moscow Evening Institute of Mechanical Engineering. Despite its clumsy name, its training was excellent.) He received numerous Soviet medals, citations, and awards. As one instance of his ability, managers didn’t think he could quickly design, develop, and fabricate 13 indicators used for checking precision gauges, but he did in three and one half months. This increased production seventy-two fold. All the time, a jealous colleague was undermining his efforts by stealing pieces or sabotaging machines.

Despite his education, training, and ability, he was repeatedly passed over. Through the years he witnessed many less able men move up the ladder to become plant director or branch manager, but he did not get a promotion or pay raise.

During the 1930s Moscow purges, he never undressed until 4 AM, nervously awaiting a Secret Police knock at his door. Next day, he and others would silently take note of fellow employees who did not show up for work. He was aware of the foreigners who disappeared from the First State Ball Bearing Factory. When he started there, he found 362 foreigners. By 1939 only he and a Hungarian were left. Because he was a foreigner, friends begged him not to visit them.

Informers lurked everywhere. If a Russian was asked to spy on neighbors he dared not refuse else he became a suspect. Informants watched a neighbor’s comings and goings from his apartment, as well as who visited him, or what he bought at the store.

Late one night in 1943, Robinson did hear a knock on his door. He thought his time had finally come, his hand shaking as he opened it. Two agents were startled to see his face, then mumbled “Excuse us. There was some mistake.”

As I read the book, I could only feel immense sadness for this man, who lost the best years of his life in a dull, dreary, police state. He learned to control his feelings, to confide in nobody. Many times he would be sounded out–perhaps innocently–over his views on this or that, and always he responded with neutrality or political correctness. He could not afford to trust anybody. That was how he survived finally to leave the Workers’ Paradise.

Born in Jamaica about 1907, he became acclimated to bitter Moscow winters. He was there when Hitler’s wermacht and luftwaffe invaded Russia, the German army 44 miles from Moscow. The Russian government recruited every able-bodied man to age 60. In 1941 he was called for his draft physical, but was not inducted because of a bad left eye. Under fierce aerial bombardment, the streets of Moscow were barricaded against the coming onslaught as he and others were told that the factory would be moved to Kuybyshev. On the train, he beheld thousands upon thousands of people fleeing Moscow–men, women, and children, young and old–shivering while trudging icy roads carrying suitcases tied with cord. In Kuybyshev whole families shared horse stalls, with over 70 people using one toilet and one wash basin.

During the war with Germany, black bread was rationed at 600 grams (21.1 oz) a day. A sack of potatoes cost 900 rubles ($180). Robert Robinson made 1100 rubles month. He ate 7 or 8 cabbage leaves soaked in lukewarm water. Others at the factory became so weak that they could not control their bladders and urinated in their pants. Some died, collapsing on the floor in front of their machines. Every passing moment the men thought of food, its smell, its taste. After months of hunger, he began losing all energy, felt listless, and went to a doctor. As he took his shirt off, she went behind a screen and cried. He at first thought she was shocked to see his skin color, but she wept because his arms were toothpicks, his stomach stretched tight against corrugated ribs. He had not looked in a mirror for months. She told him he was at death’s doorway. She invited him to her house to dine each Sunday with her, her husband, and daughter.

He never joined the communist party because of his religious faith. He could not accept atheist doctrine. He saw through a racist, repressive system, and was watchful that he not suggest even a nuance of deviant political behavior. He was made to act in a Mosfilm propaganda movie, Deep Are The Roots, then considered a classic in Russia, about racism in the United States. When asked as an “expert,” Robinson told the director that the movie was over-the-top, extremely overdone, but the director had his own career at stake and probably could not listen.

During 44 years in Soviet society, Robert Robinson found that the deepest discrimination was against blacks and orientals. In his book he notes that in the USA people may or may not condone institutional and racial discrimination but they do recognize that it exists. In the USSR, officially and socially, such discrimination did not occur. To admit the contrary would have been to violate the Soviet agenda of equality and brotherly love. He states that he “could never get used to Russian racism. They prided themselves on freedom from prejudice, so racism was especially virulent.”

During the 1930s he met and chatted on a park bench with black American poet Langston Hughes. He met and spent evenings with the hugely talented and internationally famous American Paul Robeson (athlete, actor, orator, concert singer, lawyer, social activist), and his wife Eslanda each time they visited Moscow. He asked Robeson as a fellow black man to intervene for him so he could escape Russia. Robeson avoided him on the issue. Eventually Robert Robinson learned from Eslanda that Paul did not want to do it because that would sour his relationship with the Soviet leadership.

After many years of trying, and through the extended efforts of Ugandan ambassadors Mathias Lubega, and Michael Ondoga, Robert Robinson was granted a visa for a vacation in Uganda. He was careful. He bought an Aeroflot round trip ticket although he never wanted to return. To reduce suspicion he took just a few rubles, packed few clothes.

From the airport gate to the aircraft he took a bus. Then it happened. In freezing cold, a coatless woman ran after the bus shouting his name. He dared not turn around. But the bus stopped and the driver called back for him. He got off. She told him he could not go because he had no vaccination papers. This was false; he had shown them and had been vaccinated. He trembled, wept inwardly, was totally devastated, but he repeated the process, the doctor this time simply signing the form without using a needle. Again he waited months and finally got approval.

The day came, and he climbed on the bus, praying silently as it neared the airplane. He boarded and feared that somebody would again call his name before the plane began taxiing. Or the pilot would be ordered to turn the aircraft around. It did not happen. He landed in Uganda. We are left to imagine the feelings that must have overwhelmed him as he stepped off, out of a police state and into the warm African sun.

This was 1974 and he found himself at the hotel feted as personal guest of Idi Amin, Ugandan President For Life. When Robinson visited Amin the President offered him Ugandan citizenship, but Robinson declined, fearing that it would bring violent wrath of the KGB down on him in this relatively unprotected country. For several years he taught at Uganda Technical College outside Kampala. In Uganda he met Zylpha Mapp, an African-American lecturer at the Teacher College. They married in 1976. Tensions and suppression grew in Uganda as Idi Amin became mentally unstable. Through the unrelenting efforts of an African-American US Information Service Officer, William B. Davis, in 1980 he and Zylpha were able to fly to the United States, where he was declared a legal U.S. resident, as he had to forfeit his U.S. citizenship many years before. On December 6, 1986, they became U.S. citizens. living in Washington, DC. He died in 1994 of cancer. Zylpha Mapp-Robinson died in 2001, age 87. (She was born August 25, 1914.)

Even in the United States he could not rid himself of a life lived in fear, caution, and suspicion. Robinson hoped that his book would reveal the USSR for the oppressive society it was. “Even now,” he said, “I have to be careful because so many people do not understand the Russian psychology, that once you have offended the Russians, you are never forgiven. Never forgiven.”

He did not intend that statement to detract from the countless ordinary Russians who befriended and helped him. He understood them as victims of the same system. He had fond memories of people such as the lady doctor who invited him to her house to dine during the Great Patriotic War against Germany.

He was aware of the immense suffering of his Russian friends. He tells the story of a lovely sixteen year old girl on her way to school. She was stopped by an aide of Lavrentiy Beria, head of MVD, Soviet Secret Police. The aide wanted her to climb in his car, but she refused. At the end of the school day, she looked out the window. The aide was still there. She knew she couldn’t call her parents, else they would be visited and probably sent to a labor camp. She had no choice. For two years she was raped by Beria, her parents in despair and anguish. After Beria tired of her, he forced the family to give up their belongings and move to Lithuania.

If you want to know about the Stalinist purges, and about the horrible sacrifices Russians made during WWII, read this book. Robinson was there. Spending most of his life in the Soviet Union, he suffered, struggled, silently wept, but endured. He lived through it all, an eye witness to history from the purges to Hitler’s invasion to Sputnik and the Cold War.

Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise, by Joy Gleason Carew

Amazon Book Description:

One of the most compelling, yet little known stories of race relations in the twentieth century is the account of blacks who chose to leave the United States to be involved in the Soviet Experiment in the 1920s and 1930s. Frustrated by the limitations imposed by racism in their home country, African Americans were lured by the promise of opportunity abroad. A number of them settled there, raised families, and became integrated into society. The Soviet economy likewise reaped enormous benefits from the talent and expertise that these individuals brought, and the all around success story became a platform for political leaders to boast their party goals of creating a society where all members were equal.

In Blacks, Reds, and Russians, Joy Gleason Carew offers insight into the political strategies that often underlie relationships between different peoples and countries. She draws on the autobiographies of key sojourners, including Harry Haywood and Robert Robinson, in addition to the writings of Claude McKay, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Langston Hughes. Interviews with the descendants of figures such as Paul Robeson and Oliver Golden offer rare personal insights into the story of a group of emigrants who, confronted by the daunting challenges of making a life for themselves in a racist United States, found unprecedented opportunities in communist Russia.

10:05 am on April 21, 2021