Is today’s leftish identity politics new? Actually, no. Its contemporary symptoms are just the latest spasm of a dominant ideology in Western high culture I term ‘left-modernism’, lashing out from the institutions where it is most deeply entrenched.

It isn’t hard to find commentary pointing to the novelty of today’s social-justice-warrior phenomenon. ‘Although political correctness has enjoyed a much longer sway over academia’, remarks Michael Rectenwald in Springtime for Snowflakes (2018), ‘social justice as such debuted in higher education in the fall of 2016 – when it emerged in full regalia and occupied campuses to avenge its monster-mother’s [postmodernism’s] death and wreak havoc upon its enemies’.

Some even contrast contemporary ‘snowflakes’ with the more free-speech-oriented 1960s. This is the argument of Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s Coddling of the American Mind (2018), which, while acknowledging earlier phases of political correctness, emphasises the importance of a fragile ‘i-generation’, which considers words to be a form of violence and wants adults to keep them safe from uncomfortable ideas.

It’s undeniable that a new lexicon – ‘snowflake’, ‘trigger warning’, ‘bias response team’, ‘safe space’ – has emerged since 2014. The epidemic of No Platforming of right-wing speakers has also taken off fairly recently. Diversity bureaucracies have expanded and become more proactive on American campuses, abetted by vague non-discrimination legislation like Title IX, which empowers left activists and administrators who wish to circumvent the procedural liberties of ‘privileged’ groups such as white men, or ideological opponents such as trans-exclusionary feminists.

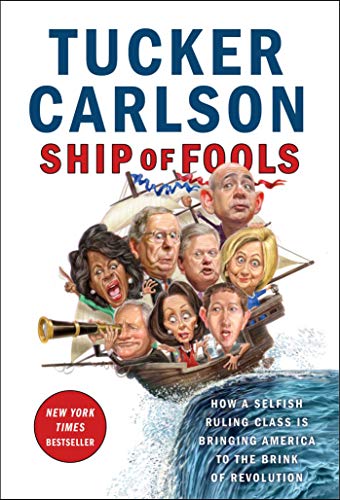

Ship of Fools: How a S...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

Ship of Fools: How a S...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

Yet, as one who first encountered political correctness in Canadian universities in the late 1980s, and vividly recalls the release of Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind in 1987, I am inclined to take a longer view. The therapeutic ethos noted by Robert Bellah in Habits of the Heart (1985) and Christopher Lasch’s Culture of Narcissism(1979) informed what Nick Haslam characterises as ‘concept creep’. That is, the broadening of the meaning of social psychology terms like bullying and prejudice, whose remit continually expanded to encompass progressively less serious behaviours. This was not conceived in an ideological vacuum, but drew strength – in part – from a progressive mission to achieve a ‘kinder, gentler’ society for the disadvantaged. There was also a non-ideological component, tied to the longstanding and commendable desire of affluent societies to reduce discomfort of all kinds and mitigate risks to children. This more materialist ‘coddling’ took place in households of all ideological stripes, be they evangelical Christian or liberal secular, whether in Japan or America.

Yet what is distinct about today’s social-justice left is its weaponisation of the idioms of safety culture. Safetyism is not the cause of SJW activism, but rather a new tool in the hands of an older left-modernist ideological tradition. Think of how preposterous the notion is that a talk happening somewhere on campus, that most students are too busy or uninterested to drag themselves to, could render them ‘unsafe’. Such events are only ‘unsafe’ for those who go out of their way to be offended, for ideological reasons. ‘Safety’ is much more of an instrumentalised social construct than a product of psychological fragility arising from a coddled upbringing. If it were, then whites, Christians or men would also be calling for safe spaces rather than undergoing reverse-coddling (having to weather attacks on their group) by developing thicker skins than their parents.

All ideologies must innovate and comment on new developments to remain fresh and vital. American Protestant fundamentalism, for example, concentrated on alcohol, trading on the Sabbath and the evils of the city in the 1920s, but changed its focus to abortion and homosexuality in the 1980s. It has experienced periodic ‘Great Awakenings’ of religious fervour. The New Left is in its third great awakening (or ‘awokening’, to quote Toby Young in the Spectator), after the two previous campus upsurges of the late 1960s and late 1980s / early 1990s. This time, it is innovating by fashioning the language of therapeutic safety culture into new slogans like ‘safe spaces’, or tactics such as bias response teams, while touting new crusades such as trans rights. Yet the older, largely admirable causes of anti-racism and anti-sexism have been revamped, while No Platforming, a strategy first used in Britain in the late 1970s, is enjoying a resurgence. The bottles carry new labels, but the ideological wine is of an older vintage.