Throughout the corona “pandemic” the Holy Grail of public health officials has been vaccination: only by vaccinating enough people—first the elderly and infirm, then all adults, and now even children—can the nefarious virus be beaten. As vaccination has proven less than wholly successful in preventing the spread of coronavirus, with studies showing rapidly declining protection from the vaccines, governments have doubled down, introducing not only “booster” shots for the vaccinated but also suggesting that the unvaccinated must be pressured and, if necessary, compelled to accept the vaccine.

Rising skepticism of the efficacy of these policies, let alone their morality, is understandable. However, it is not surprising that the medical establishment of modern states is wedded to the idea of vaccination as a panacea for disease prevention. This is, in fact, something close to the founding myth of public health: mandatory vaccination is what saved the world from the great scourges of the past, and it was introduced by heroic doctors in the face of much opposition from the egoistic, the stupid, and the establishment of silly theologians who thought that diseases were the will of God and that suffering humanity simply had to accept it. The core of this myth is the case of smallpox.

The Official History of Smallpox

The legend of smallpox and its eradication as told by most textbooks and virtually the whole medical establishment goes something like this: from about the sixteenth century, Europe was ravaged by periodic epidemics of smallpox (variola major), a disease that caused pustules to erupt all over the skin and very often, in approximately a fifth of all cases, led to death. Those who survived were often scarred for life (pockmarked). Early attempts to combat it through “variolation,” i.e., inoculation of healthy adults with puss from infected individuals, proved ineffective—while those who survived this treatment were immune, the practice also served to keep the disease alive and circulating in the population.1

Then, in 1796, the heroic Dr. Edward Jenner made the crucial discovery: anecdotal evidence suggested that milkmaids did not contract smallpox and Dr. Jenner surmised that contact with cattle had exposed them to cowpox (variola vaccinia), a disease that was much milder in humans. He therefore experimented with inoculating children with cowpox, and when he later exposed the same to smallpox through variolation, they proved to be immune. The medical establishment, in the form of the Royal Society, dismissed the good Dr. Jenner, but nothing daunted, he proceeded to promote his new treatment of “vaccination” and quickly received support from enlightened doctors and statesmen, who sponsored his scheme. Thousands were vaccinated in Great Britain within a couple of years, and the treatment spread to other European countries. Childhood vaccination was made mandatory in the “enlightened” despotisms of Bavaria (1807), Prussia (1835), Denmark (1810), and Sweden (1814) in short order and promoted everywhere else if not exactly imposed. Eventually, the English too would impose mandatory vaccination in spite of early opposition from people such as the farmer, journalist, and all-round Chad2 William Cobbett:

I was always, from the very first mention of the thing, opposed to the Cow-Pox scheme…. I, therefore, as will be seen in the pages of the Register of that day, most strenuously opposed the giving of twenty thousand pounds to JENNER out of the taxes, paid in great part by the working people….

…. This nation is fond of quackery of all sorts; and this particular quackery having been sanctioned by King, Lords and Commons, it spread over the country like a pestilence borne by the winds … [I]n hundreds of instances, persons cow-poxed by JENNER HIMSELF, have taken the real small-pox afterwards, and have either died from the disorder, or narrowly escaped with their lives!2

Reactionaries like Cobbett spreading misinformation notwithstanding, vaccination was a great success: the death toll of the smallpox fell drastically across Europe in the first decades of the nineteenth century, despite a few setbacks such as epidemics in the 1860s, the 1870s, and the 1880s. These, of course, simply proved the necessity of revaccination and that the minority of vaccine resisters had to be persuaded and cajoled to take the vaccine. If anyone doubts this, the experience of the Franco-Prussian War, fought in the middle of a Europe-wide smallpox pandemic, provides conclusive proof: the Prussian army, virtually all of whose soldiers had been vaccinated, proved highly resistant to the disease, while the French recruits, often drawn from benighted Catholic families skeptical of the vaccine, fell like flies.

Finally, the campaign led by Donald Henderson to eradicate smallpox worldwide through vaccination proved a great success. In 1980 the World Health Organization declared the disease eradicated.

Realities of Smallpox

The careful reader may have concluded from some injudicious remarks in the previous section, that I do not fully accept this story. Indeed, while some of the major facts are correct—smallpox was a major killer, and it did disappear after the global campaign—the role of vaccination and especially of mandatory vaccination is greatly exaggerated. Two simple facts show this:

- The decline in mortality from smallpox across Europe began in 1800, before the vaccine was widely distributed and before it was made mandatory anywhere, and it is therefore simply impossible to credit this decline to Jenner and the vaccine.

- There were epidemics in practically every decade thereafter, but in the 1890s fatality fell through the floor—by the early 1900s, smallpox was practically indistinguishable from chicken pox. The reason was that a new strain of the virus, variola minor, developed and outcompeted the lethal strain.

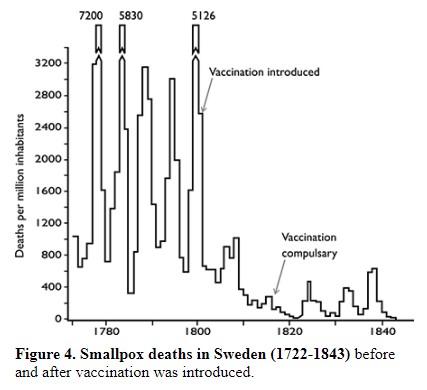

The first point is easily seen in Henderson’s own graph:3

Similar graphs could be replicated for all European countries.4 The idea that vaccination caused the decline is obviously untenable, as the practice of vaccination did not spread that widely instantly. Early compulsory vaccination (Bavaria in 1807, Denmark in 1810) also came after the decline.

If the decline in overall mortality is not due to the vaccine, did it not at least limit epidemics when they did occur? The Franco-Prussian War is the clearest indicator of this, as the unvaccinated French succumbed while the Prussians remained healthy. This was and is a main piece of evidence for the efficacy of the vaccine. The only problem with it is that it’s entirely false.

First, while the Prussian army did not experience a high mortality rate from smallpox, there was a deadly epidemic in Prussia—in fact, Prussia was the country hardest hit in Europe, with a total death toll above sixty-nine thousand. Perhaps young men did not succumb, but the other Prussians did not prove as hardy. Second, while it is true that there was no compulsory vaccination in France and that rates of vaccination were low, the French soldiers were vaccinated upon enrollment. If anything, the experience of the Franco-Prussian War proved that vaccination was powerless against the epidemic of 1870–71.5

The second point is widely admitted, although Henderson still insinuates that vaccine availability was an important factor to the eradication of smallpox in Europe. Perhaps the argument could be made, though I have nowhere seen it, that vaccination led to the development of variola minor, which eventually displaced the serious strain. However, in order to see how vaccination was unimportant to the end of European smallpox, we need to return to where it all started—England.

The English Experience

While the English were initially enthusiastic for vaccination, compulsion was quickly needed to spread the practice of infant vaccination. The Act of 1840 established payment of public vaccinators out of the rates (i.e., local taxes), and the Acts of 1853, 1867, and 1871 established a system of compulsory vaccination. Parents who refused to have their children vaccinated were punished by heavy fines and imprisonment.

While the English generally complied with vaccine requirements, the compulsory acts led to the establishment of a National Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League. One important center of this league was the large industrial town of Leicester.6 It was only after the epidemic of 1871–72 that resistance to compulsion began to spread: parents asked, not unreasonably, why they should subject their children to the risks of vaccination when they died in the epidemic anyway? The antivaccination agitation culminated with a large demonstration in Leicester in March 1885 with participants from all over the country and many expressions of sympathy from abroad.7 The demonstrators carried banners with slogans such as “Liberty Is Our Birthright, and Liberty We Demand” and “The Three Pillars of Vaccination—Fraud, Force, and Folly.”

The antivaccinationists had successfully acquired control of the Corporation of Leicester in 1882, although the Board of Guardians enforcing vaccination was independent of the town council. At the same time, noncompliance with infant vaccination spread: by the mid-1880s, less than half of all infants in Leicester were vaccinated and the trend continued. In 1886, the Board of Guardians in Leicester stopped enforcement of the Vaccination Acts. The citizens of Leicester through a campaign of nonviolent protest and noncompliance had effectively nullified the Vaccination Acts. We might expect that when the next epidemic arrived in England, in 1892–94, Leicester would be particularly hard hit, but not so: only 357 cases, or 20.5 per 10,000, occurred in Leicester as compared to 125.3 and 144.2 per 10,000 in the well-vaccinated towns of Warrington and Sheffield, respectively.8 The fatality rate in Leicester was also low, at only 21 deaths, or 5.8 percent.

That Leicester did not become a plague spot is not simply due to the inefficacy of vaccination. Rather, the town developed a system of dealing with smallpox, the Leicester Method, which subsequently spread to the rest of England from about 1900.

The Leicester Method was organized by Dr. J. W. Crane Johnston, assistant medical officer from 1877–80 and medical officer from 1880–85. Johnston’s method was simple: immediate notification when a case of smallpox was discovered, admission to the hospital of the patient, and quarantine of the closest contacts. Notification had already been established, as the Town Council Sanitary Committee in 1876 decided that 2 s. 6 d. should be paid to any case of smallpox, scarlet fever, or erysipelas, who would consent to hospital admission.9 The town council, and the antivaccinationists generally, also stressed the importance of sanitation, good hygiene, and healthy living.

So successful did the Leicester experience prove that other English towns started to copy it and notification became national law in 1899. Meanwhile, vaccination rates steadily declined, but despite epidemics in 1892–94 and 1901 nothing like the old fatality rates reoccurred. Dr. Millard, who became medical officer in Leicester in 1901, spoke frequently about both the benefits of the Leicester Method and the dangers of childhood vaccination, as modified smallpox in a vaccinated adult could be a hidden source of infection and thus place the whole community at risk.

In 1948, compulsory smallpox vaccination was officially abolished, but by then the entire English population was de facto unvaccinated—and untouched by smallpox. Taking stock of the situation in 1946, Dr. G. K. Bowes said:

Its decline in the later decades of the nineteenth century was at one time almost universally attributed to vaccination, but it is doubtful how true this is. Vaccination was never carried out with any degree of completeness, even among infants, and was maintained at a high level for a few decades only. There was therefore always a large proportion of the population unaffected by the vaccination laws. Revaccination affected only a fraction. At present the population is largely entirely unvaccinated. Members of the public health service now flatter themselves that the cessation of such outbreaks as do occur is due to their efforts. But is this so? The history of the rise, the change in age incidence, and the decline of smallpox rather lead to the conclusion that we may here have to do with a natural cycle of disease like plague, and that smallpox is no longer a natural disease for this country.10

Whatever the effects of vaccination, it is clear that it was not the cause of the disappearance of smallpox from England or Europe.11 It may have contributed to the eradication of the disease in the rest of the world, but in Europe and North America, it was clearly unnecessary.

Since the disease has been declared officially eradicated, the original cowpox vaccine no longer forms part of the childhood vaccination program in any country.

Conclusion

Public health and vaccination programs rest on one central story: that they were crucial to the elimination of one of history’s greatest killers, smallpox. As we’ve seen, this is not true: vaccination was never universal across Europe and North America,12 and the decline in mortality and the disease disappeared at the same time everywhere in the Western world, despite whatever variations in public health policies there were. Even countries such as England that had de facto given up on compulsory vaccination were rid of the disease.13 As Ludwig von Mises, and the liberal tradition before him, argued ideas rule the world. The official history of smallpox is a main support for the policies of modern health authorities. If it is exposed as largely mythical, the central ideological justification for compulsory vaccination falls by the wayside.

As well as putting the lie to the official history of smallpox, the English experience shows how local populations imbued with liberal principles14 effectively nullified public health measures dictated by the central government. For those combatting coercive public health measures today, they can in this too provide inspiration.

—

1.See Donald A. Henderson, Smallpox: The Death of a Disease (New York: Prometheus Books, 2013), EPUB.

2.a. b. One example to suggest Cobbett’s character: when in exile in Philadelphia in the 1790s for angering the British military establishment, Cobbett ran a bookshop in whose window he proudly displayed a portrait of George III and published much loyalist literature.

3.Henderson, Smallpox, figure 4.

4.See the data in W. Troesken, The Pox of Liberty: How the Constitution Left Americans Rich, Free, and Prone to Infection (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), p. 77. Professor Troesken supports the standard narrative, but his data clearly shows that it cannot be true.

5.Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th ed., vol. 24 (1888), s.v. “vaccination.”

6.Stuart M. F. Fraser, “Leicester and Smallpox: The Leicester Method,” Medical History 24 (1980): 315–32.

7.See S. Humphries and R. Bystrianyk, Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History (self-pub., 2013), chap. 6, for an account of the Great Demonstration.

8.Fraser, “Leicester and Smallpox,” 322.

9.Ibid., 317.

10.G.K. Bowes, “Epidemic Disease: Past, Present and Future,” Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute 66, no. 3 (1946): 174–79, esp. 176. According to Arthur Allen, Vaccine: The Controversial History of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), p. 69, the vaccination rate in England was 50 percent in 1914 and 18 percent in 1948.

11.As an aside, it may be mentioned that the low fatality rates touted in support of compulsory vaccination are only in evidence in Scandinavia and (from the late nineteenth century) Germany. This seems a tender reed on which to support this core measure of public health.

12.Troesken, Pox of Liberty, details the American case. He overstates the impotence of national government, however, as mandatory laws on the state and local level can be just as effective as federal legislation.

13.While I have not found numbers for vaccine compliance for other European countries, I have in fact become extremely skeptical of the idea that vaccination was universal, even in the Scandinavian countries. However, as should be clear from this essay, even accepting the record of Germany or Denmark as true, it does not prove that vaccination was necessary, or even contributed to, the end of smallpox in Europe.

14.Fraser, Leicester and Smallpox, argues that the antivaccinationists were a coalition of artisans and laborers objecting to vaccination and middle-class people objecting to compulsion. Leicester was also a center of religious nonconformism.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org are not necessarily those of the Mises Institute.