Here, in the pile of rubble left where such a haughty villa once stood, was dramatic illustration of how profoundly Italy had slumped from her one-time greatness into impotence and poverty.

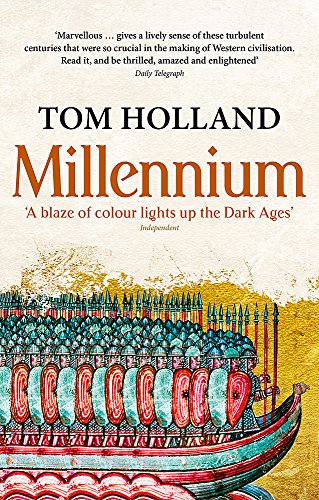

– Millennium, Tom Holland

This was ninth-century Italy, a few centuries removed from the greatness of Empire. But it wasn’t just impotence and poverty – if only it was merely these. Across vast swaths of Italian countryside, nothing of value remained – the bones picked almost clean, as Holland puts it. But Pope John VIII put it more directly at the time:

“Behold, the towns, castles, and estates perish – stripped of inhabitants.”

Millennium

Best Price: $9.12

Buy New $18.37

(as of 04:59 UTC - Details)

The Saracen slave trade was in full swing, operating on a “near-industrial scale.” Great flotillas of ships, tens-of-thousands of captives loaded for transports to the markets of Africa. The word Saracen had become synonymous with Muslim during these centuries, more specifically describing Muslim Arabs.

Millennium

Best Price: $9.12

Buy New $18.37

(as of 04:59 UTC - Details)

The Saracen slave trade was in full swing, operating on a “near-industrial scale.” Great flotillas of ships, tens-of-thousands of captives loaded for transports to the markets of Africa. The word Saracen had become synonymous with Muslim during these centuries, more specifically describing Muslim Arabs.

Something about Pope John VIII: much of his papacy was devoted to halting and reversing Muslim gains in southern Italy. Unable to gain assistance from the Franks or Byzantines, he strengthened the defenses of Rome.

He was also unable to generate meaningful support from Christians in southern Italy, these Christians having formed alliances with the Muslim invaders and slave traders. Things didn’t end well for John:

John VIII was assassinated in 882 by his own clerics; he was first poisoned, and then clubbed to death. The motives may have been his exhaustion of the papal treasury, his lack of support among the Carolingians, his gestures towards the Byzantines, and his failure to stop the Saracen raids.

Returning to Holland: this slave trading was a real business, the division of labor being quite well developed; savagery, yes, but also a system:

Persian Fire: The Firs...

Best Price: $2.68

Buy New $11.61

(as of 06:15 UTC - Details)

Persian Fire: The Firs...

Best Price: $2.68

Buy New $11.61

(as of 06:15 UTC - Details)

Some would guard the ships, others prepare the irons, others bringing in the captives. Some even specialised in the rounding up of children. The natives too – those with the determination to profit from the slavers rather than to end up as their victims – had their roles to play.

Italian Christians were hunting down their fellow Christians. The city of Amalfi was particularly noted for its role in such actions, exchanging slaves for gold dinars. Naples is also noted. Through this trade, these regions slowly pulled themselves out of the general poverty of the broader region – only at the cost of their souls.

Already in the ninth century, the markets of Naples had grown so bustling that visitors commented on how they appeared almost African in their prosperity.

Amalfi, perched on a cliff, would turn the city into a hub of international trade; merchants from this city could be found throughout the Mediterranean, flush with Saracen gold. As the trade developed, the slavers would eventually receive official backing from the rulers of Sicily. Some Christian leaders would come to believe that these depredations were driven by something more sinister than greed (and I have noted a similar possibility in our time):

Rubicon

Best Price: $3.60

Buy New $12.07

(as of 06:01 UTC - Details)

Rubicon

Best Price: $3.60

Buy New $12.07

(as of 06:01 UTC - Details)

Christendom, it appeared to them, was being systematically drained of her lifeblood: her reservoir of human souls.

And as their numbers diminished, the numbers of the enemy would increase. Erchempert, a Benedictine monk of the Abbey of Monte Cassino in Italy, would comment:

“For it is the fate of prisoners of our own race, both male and female, to end up adding to the resources of the lands beyond the sea.”

Profit was certainly the immediate motive; but with official sanction from the rulers, the entire endeavor took on the air of religiosity. The Christian captives were being spiritually disciplined, a jihad – the eternal struggle to spread the faith.

The backwardness of the Christians in southern Italy only proved the idea that God had abandoned these “infidels.” It was the natural order of things that God would send the Muslims to correct the situation.

Many Christian slaves would convert – bringing the prospect of freedom and some measure of dignity; of course, many would not. In addition, free Christians under Muslim rule were forced to pay a tax, a dhimmi. And here lies a real paradox: it was the Muslim states with the largest number of Christians that could most readily afford jihad.

By this time, Muslims would rule over North Africa, southern Europe in both Italy and Spain, and to the borders of Constantinople – all regions that were recently Christian. With the Muslims to the south and southeast, Vikings to the north and west, and Hungarians to the East, this time, perhaps, was the darkest time for Christendom since the earliest Apostolic age.

Reprinted with permission from Bionic Mosquito.