Since my time is tight and often interrupted, I will file these hit-and-run, guerrilla pieces. I’m the only one in this roadside, wall-less and dirt-floored cafe. Walking here, I paused to pet my neighbor’s cow, who’s taken an extreme liking to me. Lovingly, she licked my hand and arm with her sandpaper tongue and even bit yours truly lightly, the frisky bitch. The wind blows. It’s getting brisk in the Central Highlands.

Ea Kly has its charms, of which I’ll discuss more soon, since I’m marooned here, but today I want to talk about another hill town, Da Lat. It’s one of the cleanest and most Catholic places in Vietnam, and perhaps the most stylish and elegant. Is there some causation here?

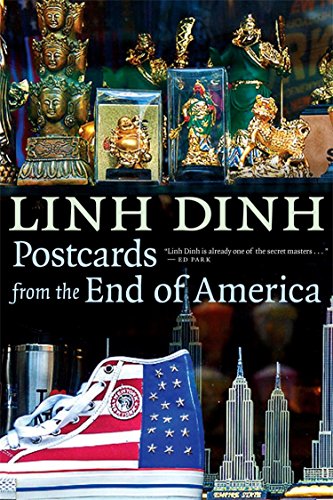

Postcards from the End...

Best Price: $7.22

Buy New $12.95

(as of 05:45 UTC - Details)

One of my uncles was a doctor in Da Lat, so I spent extended time there as a child, before 1975. This past week, I revisited this beauty. Strolling for miles up and down its hills, I was struck by the neatness of its houses, streets and alleys, and everyone, even the poorest, tended to dress more carefully and consciously than elsewhere in Vietnam. In the always hot Mekong Delta, many people have never owned a pair of shoes, socks, gloves or a jacket, but in Da Lat, several layers of clothing are often necessary before you step outside. Heat encourages nudity and a more savage state. Naked all day long, Adam and Eve must have lived in Tonga or Hawaii. The colder the weather, the more decisions you’ll have to make about your appearance, as in which scarf and knit hat should I wear this afternoon?

Postcards from the End...

Best Price: $7.22

Buy New $12.95

(as of 05:45 UTC - Details)

One of my uncles was a doctor in Da Lat, so I spent extended time there as a child, before 1975. This past week, I revisited this beauty. Strolling for miles up and down its hills, I was struck by the neatness of its houses, streets and alleys, and everyone, even the poorest, tended to dress more carefully and consciously than elsewhere in Vietnam. In the always hot Mekong Delta, many people have never owned a pair of shoes, socks, gloves or a jacket, but in Da Lat, several layers of clothing are often necessary before you step outside. Heat encourages nudity and a more savage state. Naked all day long, Adam and Eve must have lived in Tonga or Hawaii. The colder the weather, the more decisions you’ll have to make about your appearance, as in which scarf and knit hat should I wear this afternoon?

The weather, though, is but one factor in Da Lat’s stylishness. The French built this town from scratch during World War I, when colonials needed a cool place to chillax but couldn’t embark for home. Although there are only a few French villas or public buildings left, their architectural influences show up all over, and not just overtly, as in the hip roofs, balustraded balconies, flower boxes beneath double casement windows or arched trellises over gates, etc., but in the general understatedness of Da Lat’s buildings, its fine lines and angles, and nuanced proportion. In Saigon, the rich favor ostentatious gates in garish gold, but in Da Lat, you can still tell who’s loaded without being screamed at by an obnoxious entrance.

Defining the ideal existence, Vietnamese used to say, “Eat Chinese food, live in a French house, marry a Japanese wife.” Online, there’s a comment, “This saying only adds to the humiliation of the Vietnamese. We don’t achieve anything, but only favor the foreign.”

On the seven-hour car ride to Da Lat, I passed so many churches, all festive with string lights, star lanterns, flags and nativity scenes, which were also displayed at many private businesses. Gates and banners proclaimed, “Joy at God’s Birth on Earth.” Skeletal Christmas trees lined streets and Santa Clauses added cheers. It’s a bit ironic, I thought, that in Communist, supposedly Godless and traditionally Buddhist Vietnam, there is a more overt and widespread celebration of Jesus’ birth than in America.

From 1975 until 2018, I definitely witnessed not just a progressive diminution of Christmas in America, but an increasing hostility to Christianity, from the sustained deification of a slut with a holy name, Madonna, to the much ballyhooed and remunerative Piss Christ, which is a photo of a crucifix dunk in the artist’s yellowish red urine. One of Madonna’s biggest hits, Like a Prayer, features a video of her dry-humping a black saint in a church. All the other blacks are celebratory, joyous and life-affirming, while all the whites, except for Madonna, are racist, evil and violent. But hey, there’s no ideology behind any of this! It’s just a healthy and organic evolution in thinking, and what the audience can’t help but crave, if they have their heads screwed on straight.

I’m wondering if Da Lat’s relative cleanliness and orderliness can be attributed to its high number of Catholics, with their constant stress on personal responsibility and guilt, and their intimate awareness of their community, through their parish? At least once a week, Catholics pray with their immediate neighbors. By contrast, most Vietnamese who identify as Buddhists have an extremely nebulous, if not chaotic, religious life, for they study no sacred text and receive no religious instructions. In their homes, there is usually not even a statue of the Buddha, but only of a standing goddess, Kuan Yin, who is almost always referred to, most generically, as Mrs.

A typical Vietnamese Buddhist’s theology is a jumble of folk beliefs and superstitions, and I’ll cite a familial example: when my mother-in-law got sick recently after a trip, she didn’t blame it on something she ate, the long ride, the weather or her aging constitution, but the fact that she had gotten into a black car, “I knew something was wrong when I saw that black car.” I’ve also seen her pray at a Cao Dai temple and a Hindu one. Granted, many Catholics also believe in heathen magic, as in a fear of the evil eye, but they’re grounded, in theory at least, by the New Testament.

In early April of 1975, my uncle’s family showed up in our Saigon home, for Da Lat had fallen. A few days later, a rogue South Vietnamese pilot bombed the Presidential Palace, just a quarter mile from my school, La San Taberd. Like all Catholic schools, it would soon be confiscated by the new regime.

My uncle’s family managed to get out as Saigon fell, and in the US, they were sponsored by a black family in Mobile, Alabama. These kind folks took in six complete strangers, from an entirely different culture, with no common language, and this amazing generosity occurred all over America, for there were 125,000 Vietnamese refugees that needed to be resettled, in 1975 alone. Whenever I brought up this fact years later, no American knew what I was talking about.

Love Like Hate: A Novel

Best Price: $5.10

Buy New $11.14

(as of 10:10 UTC - Details)

Love Like Hate: A Novel

Best Price: $5.10

Buy New $11.14

(as of 10:10 UTC - Details)

Gaining his bearings, my uncle ran U Totem, a convenience store in Houston, then became a doctor again in Angola Prison. Another uncle practiced medicine in rural Texas. Visiting him in 1980 or so, I remember being amused by his Texan accent, but that’s what a refugee must do. Forced by violent history, he must reinvent himself overnight. Becoming American, some of my relatives are already buried there. Spat out by the beast, I’m back home, so must watch Nineveh burn from afar. The Jewish God doesn’t toy.

If a border wall is ever built, it will be to keep Americans in, turn their mental prison, already air tight, into an actual steel cage. Travel hubs have lomg become police checkpoints. Since they didn’t even dare to name their enemy, much less put up a fight, they can only wish they were refugees.

Da Lat may have some French touches, but it’s still definitely Vietnamese, so people are constantly eating and drinking on many sidewalks, and not in elegant cafes, but sitting on low stools, all wrapped up because of the cold. Being outside, Vietnamese can huddle together to observe the foot and vehicle traffic. They enjoy being in the flow. Small men with tiny, forgettable lives, we are tugged and swirled this way and that by the sweet or brutal currents. Cupping a glass of hot soymilk, I sip and belong.

Reprinted with the author’s permission.