The emptiest, dumbest platitude of our time, uttered both by establishment stiffs like the Archbishop of Canterbury and by self-styled radical leftists, is that the 1930s have made a comeback. Treating that dark decade as if it were a sentient force, a still-extant thing, observers from both the worried bourgeoisie and the edgy left insist the Thirties have staggered back to life and have much of the West in their reanimated deathly grip. Looking at Brexit, the European turn against social democracy, the rise of populist parties, and the spread of ‘yellow vest’ revolts, the opinion-forming set sees fascism everywhere, rising zombie-like from its grave, laying to waste the progressive gains of recent decades.

This analysis is about as wrong as an analysis can be. Comparing contemporary political life to events of the past is always an imperfect way of understanding where politics is at. But if we really must search for echoes of today in the past, then it isn’t the 1930s that our era looks and feels like – it’s the 1840s. In particular 1848. That is the year when peoples across Europe revolted for radical political change, starting in France and spreading to Sweden, Denmark, the German states, the Italian states, the Habsburg Empire, and elsewhere. They were democratic revolutions, demanding the establishment or improvement of parliamentary democracy, freedom of the press, the removal of old monarchical structures and their replacement by independent nation states or republics. 1848 is often referred to as the Spring of Nations.

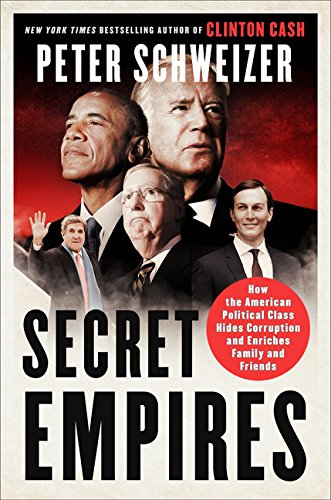

Secret Empires: How th...

Best Price: $9.41

Buy New $14.90

(as of 10:05 UTC - Details)

Sound familiar? Of course 2018 has not been as tumultuous as 1848 was. There have been ballot-box protests and street-based revolts but no attempts at actual revolutions. And yet our era also feels like a Spring of Nations. In Europe especially. There are now millions of people across Europe who want to re-establish the ideals of nationhood, of national sovereignty and popular democracy, against what we might view as the neo-monarchical structures of 21st-century technocracy. The sustained gilets jaunes revolts in France capture this well. Here we have an increasingly monarchical ruler – the aloof, self-styled Jupiterian presidency of Emmanuel Macron – being challenged week in, week out by people who want greater say and greater national independence. ‘Macron = Louis 16’, said graffiti in the gilets jaunes-ruled streets during one of their revolts. And we know what happened to him (though in 1793, of course, not 1848).

Secret Empires: How th...

Best Price: $9.41

Buy New $14.90

(as of 10:05 UTC - Details)

Sound familiar? Of course 2018 has not been as tumultuous as 1848 was. There have been ballot-box protests and street-based revolts but no attempts at actual revolutions. And yet our era also feels like a Spring of Nations. In Europe especially. There are now millions of people across Europe who want to re-establish the ideals of nationhood, of national sovereignty and popular democracy, against what we might view as the neo-monarchical structures of 21st-century technocracy. The sustained gilets jaunes revolts in France capture this well. Here we have an increasingly monarchical ruler – the aloof, self-styled Jupiterian presidency of Emmanuel Macron – being challenged week in, week out by people who want greater say and greater national independence. ‘Macron = Louis 16’, said graffiti in the gilets jaunes-ruled streets during one of their revolts. And we know what happened to him (though in 1793, of course, not 1848).

France’s February Revolution of 1848 – which brought to an end the constitutional monarchy that had been established in 1830 and led to the creation of the Second Republic – was one of the key igniters of the people’s spring that spread through Europe in 1848. Today, likewise, the gilets jaunes revolts have spread. In recent weeks yellow-vest protesters in Belgium have tried to storm the European Commission – an unprecedented event, which got strikingly little media coverage – while yellow vests in the Netherlands have called for a referendum on EU membership and in Italy they have gathered to express support for their Eurosceptic government. That election in Italy was a key event of 2018. Coming in March, it brought to power the League and the Five Star Movement, parties loathed by the EU establishment, and in the process it shattered the delusions that had gripped many European observers following the election of Macron last year – that Macron’s victory represented the fading-away of the populist moment. Italy disproved that, French revolters confirmed it, and local and national elections everywhere from Germany to Sweden added further weight to the fact that the populist revolt is not going away anytime soon.