Politica: Politics Methodically Set Forth and Illustrated with Sacred and Profane Examples, by Johannes Althusius

The lingering question I have had since being introduced to and reading Althusius’ work is…what happens at the top? How is one to deal with the tyrant? We have seen in my previous post that Althusius has offered building blocks in society that are voluntary and / or offer means of secession. His building blocks recognize man as he is – starting with the family and forming relationships based on subjective values.

But now, what about at the top? What happens at the level of the commonwealth? Althusius addresses this in a chapter entitled “Tyranny and Its Remedies.” I will say up front: parts of Althusius’ construction is confusing to me in detail; however, on the important points of remedy, I believe his message is clear.

A tyrant is therefore one who, violating both word and oath, begins to shake the foundations and unloosen the bonds of the associated body of the commonwealth. A tyrant may be either a monarch or polyarch that through avarice, pride, or perfidy cruelly overthrows and destroys the most important goods of the commonwealth, such as its peace, virtue, order, law, and nobility…

Politica

Best Price: $4.91

Buy New $9.00

(as of 07:10 UTC - Details)

The tyrant is one who overthrows the fundamental laws of the realm, or acts in a manner contrary to piety and justice; he plunders in the same manner as a conquering enemy. Althusius goes on to discuss various levels and types of tyranny, and remedies short of what could be considered an ultimate remedy.

Politica

Best Price: $4.91

Buy New $9.00

(as of 07:10 UTC - Details)

The tyrant is one who overthrows the fundamental laws of the realm, or acts in a manner contrary to piety and justice; he plunders in the same manner as a conquering enemy. Althusius goes on to discuss various levels and types of tyranny, and remedies short of what could be considered an ultimate remedy.

My focus will be on the ultimate remedy / remedies, as it is here where the last and most important building block of Althusius’ theory will be weighed by those who look for a decentralized and voluntary society.

…we are now to look for the remedy by which [the tyrant] may be opportunely removed.

It is left to the ephors – let’s call them senior figures who have responsibility to support the supreme magistrate in properly fulfilling his duty and correcting and resisting him – or removing him – if the tyrant does not return to proper governance. If they cannot correct the tyrant, “they depose him and cast him out of their midst.”

These ephors can work collectively or individually to resist the tyrant “to the best of their ability.” However, “resisting” should not be assumed the same as “removing.”

Subjects and citizens who love their country and resist a tyrant, and want the commonwealth and its rights to be safe and sound, should join themselves to a resisting ephor or optimate.

Those who refuse to assist in this resistance are also to be considered enemies. Again, resistance is one thing; removal is a different issue: this can be done only by the ephors as a whole, not by one or some subset of ephors. All is not lost, however, for the subset of ephors who find the magistrate a tyrant:

However, it shall be permitted one part of the realm, or individual ephors or estates of the realm, to withdraw from subjection to the tyranny of their magistrate and to defend themselves.

So, it is in theory possible to secede from the realm of the tyrannical magistrate – and it should be recalled from my prior post that it is possible for the lower levels to secede from a province. In other words, secession or withdrawal is, in theory, possible at all levels of society under Althusius’ concept. Althusius states this plainly:

Thus also subjects can withdraw their support from a magistrate who does not defend them when he should, and can justly have recourse to another prince and submit themselves to him. Or if a magistrate refuses to administer justice, they can resist him and refuse to pay taxes.

Private persons do not have the rights of the ephors; they cannot resist directly. They can, however, submit themselves to another prince. Private persons can also resort to defense if they find themselves forced to be servants of tyranny or forced to do something contrary to God.

Althusius recognizes that those so choosing to secede – whether via the public ephors or whether as a private person – must “defend themselves.” Tyrants do not, after all, easily let others leave freely.

Althusius also raises the possibility of tyrannicide:

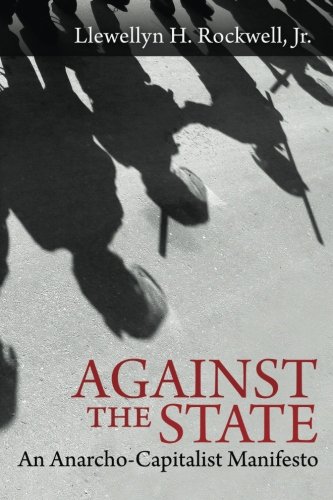

Against the State: An ...

Best Price: $5.02

Buy New $5.52

(as of 11:35 UTC - Details)

Against the State: An ...

Best Price: $5.02

Buy New $5.52

(as of 11:35 UTC - Details)

In one instance only can he justly be killed, namely, when his tyranny has been publicly acknowledged and is incurable…

Conclusion

Althusius has done a commendable job of recreating the governance model of the European Middle Ages within the reality that the universal Church no longer existed as an institution of authority. I can only return to my thought that this missing piece is the critical piece, as without such a universal authority – one that had the respect of the kings and nobles – there was no institution powerful enough to keep the tyrannical ruler in check. Excommunication mattered.

The closest we can get today? Christian leaders that start speaking as if they believe the Bible and Christ’s message. Those who do will lose many, but from what’s left perhaps an ethic can be restored.

I discovered Althusius thanks to Gerard Casey. I will conclude this examination with Casey’s assessment of Althusius’ political philosophy:

Had the Althusian and not the Bodinian conception of the locus of sovereignty prevailed, the course of political history might well have been very different.

Reprinted with permission from Bionic Mosquito.