One definition of bibliophilia is a great or excessive love of books. (A synonym for bibliophilia used by Theodore Dalrymple is Bibliomania.) I have not been diagnosed by an “expert” using the DSM-5, but I think I “suffer” from this “disorder.” (Note use of quotes to indicate sarcasm.) Nonetheless, I am almost always reading books or thinking about books and I have written about a dozen LRC posts on various books so I think I have bibliophilia.

There are at least two types of bibliophiles, one who loves and collects physical books and one who loves to read books. I am in the latter category as most of the books I have read in my life were borrowed from a library. Perhaps my favorite library was the Perkins Library at Duke University. I spent a lot of time there as a grad student looking for books and reading not associated with my thesis (in fluid mechanics). It is in the heart of the neo-gothic West Campus. In my most recent visit there a coffee shop has been added as an extension to the back of the building. It is notable for me as perhaps the best example I know of using modern steel and glass construction, but with lots of wood in the interior, that beautifully maintains architectural motifs (note the arches).

However, I do like physical books too. One book I borrowed from Perkins was Dante’s La Vita Nuova. I think I was probably the only person to have ever borrowed this volume and it appeared to be printed in the 19th century. The end paper in the front of the book included an elegant print of Beatrice with a protective sheet of tissue paper. The folded sheet construction included the printer’s marks on the bottoms of some of the pages. The font was also quite distinctive, especially the f’s and s’s that included flowery scrolls. But I apologize for my ignorance in describing the book’s construction; it does not pertain to my strain of bibliophilia.

In my intellectual development there is a special connection to this library. There was a display in the lobby that contained the favorite books of individuals who had made donations to the library. The latest book by William Buckley was in the display. A short caption mentioned that this was always the current favorite of Ruth Matthews. It also mentioned that she had worked at National Review and lived in Durham (where Duke is located). At that time I admired Buckley and NR (times have changed!) so much that I asked for her phone number from the library staff and invited her to lunch. We did have lunch on that occasion and many more times as we became great friends. I had expected to meet a retired secretary who might be able to tell me tales of Buckley, Chambers, Burnham, etc. She was much more than a secretary, being a writer and a scholar in her own right. Her late husband J. B. Matthews was well known but is now obscure. It was her donation of his papers that made her a Friend of the Library. In many ways J. B. was an archetype of the 30s socialist intellectual who turned into an anti-communism. He eventually realized that far from being a salve for the human condition, socialism is a virus that destroys people, and then had the integrity and courage to fight what he had previously been fighting for. By the 50s he was given the moniker Mr. Anti-Communist and J. B. and Ruth maintained a right-wing salon in their New York penthouse. Frequent visitors included Ayn Rand and Joseph McCarthy, among many other writers, politicians, and anti-communists from other walks of life.

Human Action: A Treati...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

Human Action: A Treati...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

During the administration of Bush senior my interest in economics began to grow primarily because the economists were so consistently wrong. Compared to engineering calculation, I thought economic calculation was disastrous. I determined to study the subject. On one occasion visiting Ruth’s apartment I noticed a book titled Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, sitting on her coffee table. I had never heard of the author, Ludwig von Mises, but Ruth told me they had been close friends. Margit von Mises mentions Ruth in her book about her life with Ludwig. I borrowed and read Human Action; thus I began to study economics and started on the road to libertarianism. As I think back now, perhaps von Mises himself had given that book to J. B. and Ruth. Wow!

I have a friend who had earned his PhD in the notorious Duke English Department during those days chaired by Stanley Fish, the noted postmodernist who gave away the bank to a motley assortment of poststructural marxists who were known around campus to drive expensive sports cars. Fish himself had an academic reputation as a friend of feminists and workers. He had quite a different reputation around campus. One late afternoon sitting at the little bar at a beer joint on campus (appropriately named the Hideaway) my friend mentioned how Fish was horrible to his female assistant. Then one after another the handful of other campus workers and grad students sitting at the bar provided their personal anecdotes of how much of a jerk he was.

My friend and I used to have many discussions about postmodernism and cultural marxism including the possible existence of a literary canon. As I was right wing and an engineer I argued for the existence of truth and at least some ranking of good versus bad literature. He graduated from Princeton and from his milieu had to argue against it. But he came from good midwest roots and his ideology began to turn, perhaps due to my influence as well. He did get a teaching post after graduation, but as a heterosexual white male he had no chance for a tenure track university job. The odds were even worse with his turn to the right (teaching Witness by Whittaker Chambers no less). He ended up going to law school to become a productive corporate lawyer with a beautiful family and living back in the midwest flyover country. That life may all sound prosaic, but he still found the time to write a nice novel.

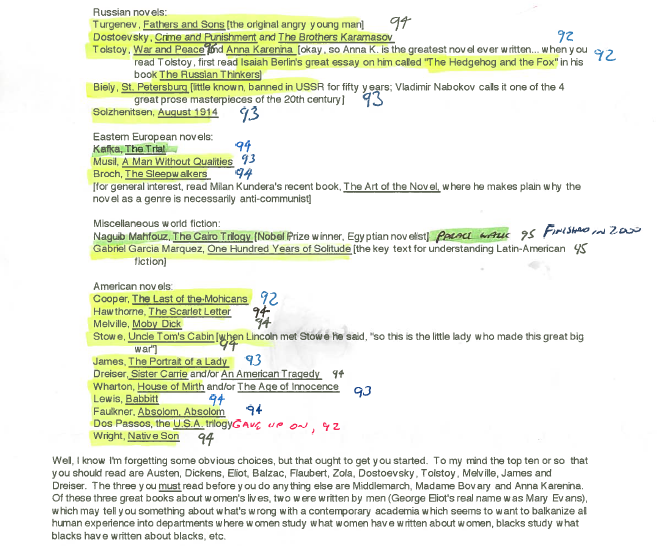

During the period of my postdoc I was reading a lot. As an engineering student I had read very little literature so I embarked upon a remedial education project to read the greatest novels ever written. I asked my friend for a canonical list (the one that we had argued about) of perhaps the greatest 30 novels (see appendix). It was a great exercise for me. According to him the three greatest were Middlemarch by Eliot, Madame Bovary by Flaubert, and Anna Karenina by Tolstoy. There is a similar focus to the plots in each of these novels. A young, beautiful, intelligent, and passionate woman marries an older, dull, and passionless man. It is interesting to note how the English, French and Russian deal with such a situation. In Middlemarch Dorthea outlives her old man and ends up marrying Will. There was never any adultery in their relationship and if everything does not turn out ‘happily ever after’ at least they are generally happy. In Madame Bovary on the other hand, Emma’s passions make her almost an evil person. In fact almost every character is nasty. The basic theme being that below the facade of bourgeois respectability lurks great evil. Thus in the end Emma kills herself and everyone is miserable. Tolstoy sort of splits the difference with Anna Karenina. The novel begins with Kitty trying to decide who she loves (Levin or Vronsky) and her sister Dolly’s marriage breaking up because of the philandering of her ne’er-do-well husband Oblonsky. Oblonsky’s sister is Anna, who arrives from St. Petersburg to patch up the rift in the marriage. On the fateful day of a ball Kitty turns down the proposal of the solid, truthful and passionate Levin because she expects a proposal from the rich, dashing Count Vronsky. At the ball Vronsky falls in love with Anna. Anna is taken with him as well and realizes what has happened as far as Kitty’s broken heart. She gets on the train back to St. Petersburg the next day. But Vronsky follows and catches her to express his love (probably one of the most romantic passages in all literature). Kitty is heartbroken and takes several months to recover. In a couple of years she ends up marrying Levin. Anna and Vronsky have an affair. She eventually leaves her husband Karenin. Thus there are two couples to follow. One couple finds a life of love and happiness while the other ends in tragedy. Anna is outcast from society and cannot see her son. Eventually the pressures on her drive her to commit suicide.

Of these I really loved Anna Karenina. There were so many passages that I copied and shared with special friends. Here is one about Dolly that is even much more poignant for me now that I have children (just one) myself.

Peace with six children was next to impossible. One would fall ill, another would threaten to fall ill, a third would be without something necessary, a fourth would show symptoms of a bad disposition, and so on, and so on. Rare indeed were the brief intervals of peace. But these cares and anxieties were for Dolly the sole happiness possible. Had it not been for them, she would have been left alone to brood over her husband who did not love her. And besides, hard though it was for the mother to bear the dread of illness, the illnesses themselves and the grief of seeing signs of evil tendencies in her children – the children themselves were even now repaying her in small joys for her sufferings. Those joys were so small that they passed unnoticed, like gold in sand, and in trying moments she could see nothing but the pain, nothing but the sand; but there were good moments, too, when she saw nothing but the joy, nothing but the gold.

I should add, for me and my family it is almost all gold.

In some ways it is great to be a bibliophile like me today, that is one who wants to read books, not collect them. A couple of years ago I took Lew Rockwell’s advice and bought a Kindle. I certainly do miss holding real books in my hands, but there are some great advantages to electronic books. To name a few, I can carry many books easily within the Kindle memory. I can read without any ambient light. I can highlight sections and take notes, which I can then download to incorporate into articles. I can search the text. I can look up the definition of a word or a Wikipedia entry at a touch. But the best modern feature of electronic books is that there is a world of books easily available online for free. Who needs a library now. The first and foremost for me has been the Mises Institute. I have found a wide range of books at the University of Adelaide ebooks online. I can add that there are not just books available, for example see the project of Ron Unz at Unz.com to compile journal literature. One can find a listing of free ebook sites here.

My friend’s novel list was broken into country categories. The French list included Eugenie Grandet (Balzac), The Red and the Black (Stendhal), Madame Bovary, and Nana (Zola). Boy do these books take a negative view of people and of life in general. Les Miserables (Hugo), that was also on the list, does have redeeming characters, but some real nasty ones too. The last French entry, In Search of Lost Time (Proust), is too different and strange to put in the same category as the others but added to my overall negative view of the French. Add those horrible French postmodern philosophers and the inherent socialism in modern France compared to practical and capitalistic England. Add language and beer and you can see why my favoritism tilted heavily for the Lions over the Bleus.

An Austrian Perspectiv...

Best Price: $1.99

Buy New $29.00

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

An Austrian Perspectiv...

Best Price: $1.99

Buy New $29.00

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

But now I live in France and I am French and my opinion of the French vis-à-vis the English has changed. But it is not only for those obvious reasons. I recently wrote about Rothbard’s Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. What I didn’t mention but what also was striking to me was Rothbard’s view of English vs French economists. That is, Smith, Ricardo and Mill received withering criticism; while Cantillon, Turgot, and Say are given extreme praise. I had a rather Whig view of English history from Books such as Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities, ancient freedoms solidified by the bloodless Glorious Revolution. On-the-other-hand, France had the revolution with the terror, regicide, and Bonaparte. But I recently read another book after browsing the University Adelaide website that has changed my understanding of English history; it is The History of England from the First Invasion by the Romans : to the Accession of King George the Fifth : Volume 8 by Hilaire Belloc. A generation before the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was the civil war, complete with terror (e.g., see the invasion and conquest of Ireland), the execution of the king, and a military dictatorship (the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell). The iconoclastic destruction of art would make the Islamic State proud. Even the nominally libertarian group called the Levelers who favored religious freedom had the exception of Catholics. Thus English history has the horrible periods like the French.

Why am I thinking about these things now? I was browsing at one site as one would at a used bookstore or a library and fell upon The George Sand-Gustave Flaubert Letters, Translated by A. L. McKenzie With an Introduction by Stuart Sherman. I have never read Sand but am now interested in part because she was an incredible character with notorious love affairs and scandalous behaviour (dressing as a man as a young rebelious writer). As for Flaubert, Madame Bovary left me cold. I also read his Salammbo. It is interesting and strange, but not what I would recommend to anyone. But this book of correspondence has changed my opinion of the these two very French people. First consider these excellent descriptions of Sand and Flaubert from the introduction:

George Sand in the mellow autumn of her life is for us at her most attractive phase. The storms and anguish and hazardous adventures that attended the defiant unfolding of her spirit are over. In her final retreat at Nohant, surrounded by her affectionate children and grandchildren, diligently writing, botanizing, bathing in her little river, visited by her friends and undistracted by the fiery lovers of the old time, she shows an unguessed wealth of maternal virtue, swift, comprehending sympathy, fortitude, sunny resignation, and a goodness of heart that has ripened into wisdom.

For Flaubert, too, though he was seventeen years her junior, the flamboyance of youth was long since past; in 1862, when the correspondence begins, he was firmly settled, a shy, proud, grumpy toiling hermit of forty, in his family seat at Croisset, beginning his seven years’ labor at L’Education Sentimentale, master of his art, hardening in his convictions, and conscious of increasing estrangement from the spirit of his age. He, with his craving for sympathy, and she, with her inexhaustible supply of it, meet; he pours out his bitterness, she her consolation; and so with equal candor of self-revelation they beautifully draw out and strengthen each the other’s characteristics, and help one another grow old.

Robert Higgs recently wrote in his blog about the concept that “The personal is political.” He explains that this “is a slogan that has been around for a long time, used especially though not exclusively by radical feminists. In practice it has served as an exhortation that people make ideology the sole dimension of their personal identity, that they set aside all other bases on which to evaluate their relations with other people and order their conduct even in their most intimate dealings with others.” That is, to live by this proposition will make life unbearable. In the Sand-Flaubert letters I find the evidence, especially from Sand, for the wisdom to base the personal on love, not politics during the trying times of the Franco-Prussian war and the revolutionary Paris Commune. One aspect that says so much to me that was positive about both is how often they corresponded about helping others professionally, monetarily (even though they were not rich), and simply being neighbourly.

Following below I provide several pearls of wisdom from Sand for your benefit.

As for me, when money comes, I say, “So much the better,” without excitement, and if it does not come, I say, “So much the worse,” without any chagrin. Money not being the aim, ought not to be the preoccupation.

And if one does not take life like that, one cannot take it in any way, and then how can one endure it? I find it amusing and interesting, and since I accept EVERYTHING, I am so much happier and more enthusiastic when I meet the beautiful and the good. If I did not have a great knowledge of the species, I should not have quickly understood you, or known you or loved you. I can have an enormous indulgence, perhaps banal, for I have had to practice it so much; but appreciation is quite another thing, and I do not think that it is entirely worn out in your old troubadour’s mind. I found my children still very good and very tender, my two little grandchildren still pretty and sweet. This morning I dreamed, and I woke up saying this strange sentence: “There is always a youthful great first part in the drama of life. First part in mine: Aurore.” The fact is that it is impossible not to idolize that little one. She is so perfect in intelligence and goodness, that she seems to me like a dream.

In the 18th century the chief business was diplomacy. “The secrecy of the cabinets” really existed. The peoples still were sufficiently amenable to be separated and to be combined. That order of things seems to me to have said its last word in 1815. Since then, one has hardly done anything except dispute about the external form that it is fitting to give the fantastic and odious being called the State.

But I don’t rage any more, I laugh; I know too much of all that to get excited about it, and I shall tell you some fine stories about it when we meet. However, as I am an optimist just the same, I look at the good side of things and people; but the truth is that everything is bad and everything is good in this world.

Yet I did not see myself as a progressivist and a humanitarian. That doesn’t matter. I had some illusions! What barbarity! What a slump! I am wrathful at my contemporaries for having given me the feelings of a brute of the twelfth century! I’M STIFLING IN GALL! These officers who break mirrors with white gloves on, who know Sanskrit and who fling themselves on the champagne, who steal your watch and then send you their visiting card, this war for money, these civilized savages give me more horror than cannibals. And all the world is going to imitate them, is going to be a soldier! Russia has now four millions of them. All Europe will wear a uniform. If we take our revenge, it will be ultra-ferocious, and observe that one is going to think only of that, of avenging oneself on Germany! The government, whatever it is, can support itself only by speculating on that passion. Wholesale murder is going to be the end of all our efforts, the ideal of France!

If today it is the people that is under foot, I shall hold out my hand to the people — if it is the oppressor and executioner, I shall tell it that it is cowardly and odious. What do I care for this or that group of men, these names which have become standards, these personalities which have become catchwords? I know only wise and foolish, innocent and guilty. I do not have to ask myself where are my friends or my enemies. They are where torment has thrown them. Those who have deserved my love, and who do not see through my eyes, are nonetheless dear to me. The thoughtless blame of those who leave me does not make me consider them as enemies. All friendship unjustly withdrawn remains intact in the heart that has not merited the outrage. That heart is above self-love, it knows how to wait for the awakening of justice and affection.

Well! the moral abasement of Germany is not the future safety of France, and if we are called upon to return to her the evil that has been done us, her collapse will not give us back our life. It is not in blood that races are re-invigorated and rejuvenated.

You must not be sick, you must not be a grumbler, my dear old troubadour. You must cough, blow your nose, get well, say that France is mad, humanity silly, and that we are crude animals; and you must love yourself, your kind, and your friends above all.

But I see that this poor friend was, like you, one who DID NOT GET OVER HIS ANGER, and at your age I should like to see you less irritated, less worried with the folly of others. For me, it is lost time, like complaining about being bored with the rain and the flies.

Can one live peaceably, you say, when the human race is so absurd? I submit, while saying to myself that perhaps I am as absurd as everyone else and that it is time to turn my mind to correcting myself.

Pray why is your poor little mother so irritable and desperate, in the very midst of an old age that when I last saw her was still so green and so gracious? Is her deafness sudden? Did she entirely lack philosophy and patience before these infirmities?

I have not mounted as high as you in my ambition. You want to write for the ages. As for me, I think that in fifty years, I shall be absolutely forgotten and perhaps unkindly ignored. Such is the law of things that are not of first rank, and I have never thought myself in the first rank. My idea has been rather to act upon my contemporaries, even if only on a few, and to share with them my ideal of sweetness and poetry. I have attained this end up to a certain point; I have at least done my best towards it, I do still, and my reward is to approach it continually a little nearer.

Appendix

==========