The international journal Science of the Total Environment has just published a compelling study from the Republic of Korea, where autism prevalence is high. The study identifies a strong relationship between prenatal and early childhood exposure to mercury and autistic behaviors in five-year-olds.

Lead author Jia Ryu and coauthors acknowledge mercury’s potential for neurotoxicity straight away but choose to characterize previous findings on the mercury-autism relationship as “inconsistent.” They attribute the seeming lack of consistency, in part, to methodological issues, especially flagging problematic cross-sectional study designs that measure autistic behaviors and mercury levels (in either blood or hair) at a single point in time. To rectify these methodological weaknesses, Ryu and coauthors report on data from a multi-region longitudinal study in the Republic of Korea called the Mothers and Children’s Environmental Health (MOCEH) study.

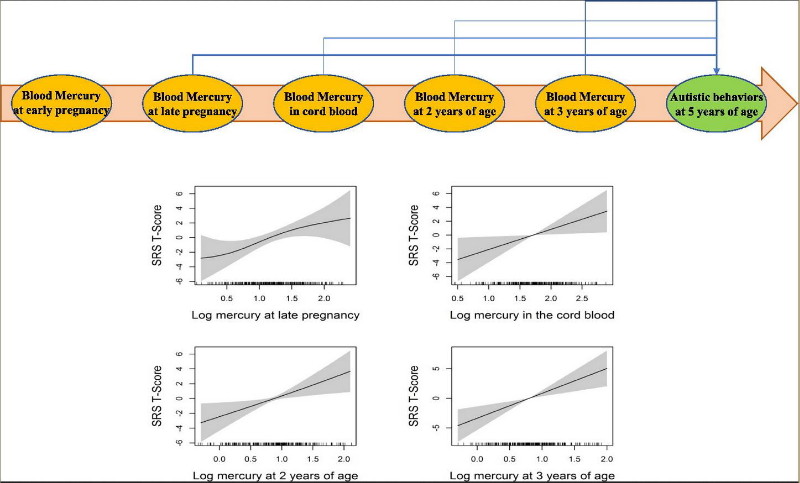

The ongoing MOCEH study examines environmental exposures during pregnancy and childhood and their effects on children’s growth and development. A unique feature is that it includes five different blood samples: maternal blood from early and late pregnancy; cord blood; and samples from children at two and three years of age. In addition, the study asks mothers to complete three follow-up surveys and—when their child reaches age five—the 65-item Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), which assesses autistic behaviors.

Key Results

Ryu and colleagues present available data for 458 (26%) of the 1,751 mother-child pairs originally recruited into the MOCEH study. What are their key findings?

–First, the researchers report a significant linear relationship between mercury exposure and autistic behaviors (as indicated by a scaled score called an SRS T-score). Strikingly, they find that with a doubling of blood mercury levels at four time points (late pregnancy, cord blood, and at two and three years of age), SRS T-scores are significantly higher.

–Ryu et al. also look specifically at SRS T-scores greater than or equal to 60. Sixty and above is the accepted threshold for detecting “mild to moderate” deficits of social behavior related to autism; scores of 76 or more are in the “severe” range. In these analyses, the same linear relationship holds for late pregnancy and birth (i.e., cord blood). With a doubling of blood mercury levels at these two time points, there is a 31% and 28% increase, respectively, in the risk of an SRS T-score of 60 or more.

–Finally, the researchers identify a stronger association between late-pregnancy mercury exposure and autistic behaviors in five-year-old boys versus five-year-old girls, perhaps due to mercury’s endocrine-disrupting properties.

Limitations

Although the Korean study has many methodological strengths, it displays some curious omissions and contradictions. For example, the authors note, almost in passing, that they measured total mercury “instead of methylmercury,” but they discount any potential relevance of ethylmercury from thimerosal-containing vaccines. In support of this dismissive stance, they cite a 2014 meta-analysis that failed to find any “material associations” between thimerosal exposure and ASD or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They do not mention that the authors of the meta-analysis actually urged readers to interpret their results with caution “since the number of epidemiological studies on this issue [is] limited and still at an early stage.”

Ryu and coauthors also repeat the canard that methylmercury is the only form of organic mercury capable of inducing neurotoxic effects because of ethylmercury’s shorter blood half-life compared to methylmercury. This statement is disingenuous in light of the well-documented fact that methylmercury and ethylmercury share numerous mechanisms of toxicity. Moreover, strong evidence from infant primates shows that injected thimerosal has a much slower half-life in the brain than in the blood, and infants exposed to injected thimerosal accumulate harmful inorganic mercury (an end product of thimerosal) in the brain to a far greater extent than infants exposed to orally ingested methylmercury. Due to these differences, blood mercury levels are not a suitable indicator of injected thimerosal’s potentially adverse effects on the brain. Finally, it is biologically plausible that simultaneous exposure to both forms of mercury (ethyl and methyl) may result in additive and synergistic neurotoxic effects.

The Korean Context

Interestingly, fully a third of Ryu’s study population (32.5%) had an SRS T-score of at least 60 (versus about 18% of U.S. children). In 2011, a South Korean study of over 23,000 seven-to-twelve-year-old children made headlines by reporting a national ASD prevalence of 2.64%—or 1 in 38 children. The Republic of Korea’s immunization rates have been steadily climbing (along with autism rates) since the 1990s, with nearly universal (98%-99%) coverage, for example, for measles and DTP3 in one-year-olds. Is it simply a coincidence that “neuro-psychiatric conditions” represent the single largest cause of “years of healthy life lost due to disability” (YLD) in the Republic of Korea? As per the nation’s crowded immunization schedule, Korean infants receive three doses of the thimerosal-containing Hepavax-Gene® hepatitis B vaccine at birth, one month, and six months. Analyses of Korean children’s mercury levels have paid insufficient attention to developmentally vulnerable infants’ exposure to ethylmercury in the form of thimerosal. Surely, identifying and lowering all sources of mercury exposure is a logical next step to improve children’s health and quality of life.

Reprinted with permission from Collective Evolution.