In May of 1967, a former CIA officer named Tom Braden published a confession in the Saturday Evening Post under the headline, “I’m glad the CIA is ‘immoral.’” Braden confirmed what journalists had begun to uncover over the previous year or so: The CIA had been responsible for secretly financing a large number of “civil society” groups, such as the National Student Association and many socialist European unions, in order to counter the efforts of parallel pro-Soviet organizations. “[I]n much of Europe in the 1950’s,” wrote Braden, “socialists, people who called themselves ‘left’ — the very people whom many Americans thought no better than Communists — were about the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism.”

The centerpiece of the CIA’s effort to organize the efforts of anti-Communist artists and intellectuals was the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Established in 1950 and headquartered in Paris, the CCF brought together prominent thinkers under the rubric of anti-totalitarianism. For the CIA, it was an opportunity to guarantee that anti-Communist ideas were not voiced only by reactionary speakers; most of the CCF’s members were liberals or socialists of the anti-Communist variety. With CIA personnel scattered throughout the leadership, including at the very top, the CCF ran lectures, conferences, concerts, and art galleries. It helped bring the Boston Symphony Orchestra to Europe in 1952, for example, as part of an effort to convince skeptical Europeans of American cultural sophistication and thus capacity for leadership in the bipolar world of the Cold War. By purchasing thousands of advance copies that it gave away for free, the CCF supported the publication of many of the era’s anti-Communist classics, such as Milovan Djilas’ The New Class. But its most impressive achievement was a stable of sophisticated literary and political magazines. The CCF’s flagship journal was the London-based Encounter, but it also published Preuves in France, Tempo Presente in Italy, Forum in Austria, Quadrant in Australia, Jiyu in Japan, and Cuadernos and Mundo Nuevo in Latin America, among many others.

Current Prices on popular forms of Silver Bullion

Through the CCF, as well as by more direct means, the CIA became a major player in intellectual life during the Cold War — the closest thing that the U.S. government had to a Ministry of Culture. This left a complex legacy. During the Cold War, it was commonplace to draw the distinction between “totalitarian” and “free” societies by noting that only in the free ones could groups self-organize independently of the state. But many of the groups that made that argument — including the magazines on this left — were often covertly-sponsored instruments of state power, at least in part. Whether or not art and artists would have been more “revolutionary” in the absence of the CIA’s cultural work is a vexed question; what is clear is that that possibility was not a risk they were willing to run. And the magazines remain, giving off an occasional glitter amid the murk left behind by the intersection of power and self-interest. Here are seven of the best, ranked by an opaque and arbitrary combination of quality, impact, and level of CIA involvement.

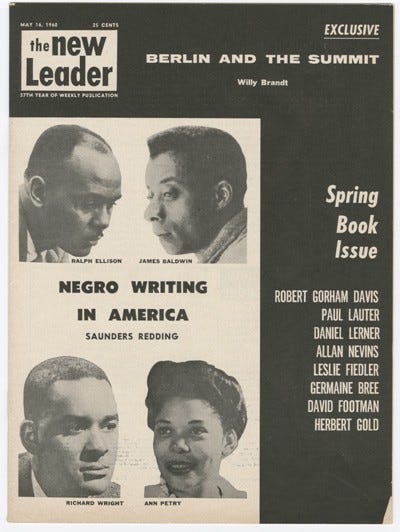

7. The New Leader

The New Leader was founded in the nineteen twenties as a voice for American socialism, but by the dawn of the Cold War, it focused incessantly on establishing the totalitarian and imperialist character of the Soviet Union. During The New Leader’s heyday in the late forties and early fifties, its editor was Sol Levitas. The New Leader’s relationship with the CIA wasn’t always easy; the CIA actually thought that Levitas’s anti-Communism was too ferocious, unrelenting, and “conservative.” The New Leader argued consistently that Soviet society was totalitarian in nature and Communism everywhere was controlled by the Kremlin, while the CIA wanted a more moderate and “sophisticated” voice that would appeal to the European left. In spite of its strident anti-Communism, The New Leader remained progressive in the context of U.S. domestic politics; it was one of the first publications to publish Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail.