Ireland was much on my mind these past weeks. As we watched the first stage of Britain’s divorce from the European Union, the ever-rebellious Scots and Northern Irish were getting ready for a new struggle for independence.

St Patrick’s Day arrived last week, commemorating the patron saint of Ireland, a grand and glorious day when Irish and adopted Irish whoop it up, drink too much, sing traditional songs and get into fist fights over nothing.

Then, a prominent leader of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) Martin McGuinness died, aged only 67. McGuinness had long battled for British-ruled Northern Ireland to join the Irish Republic.

Why are the most advertised Gold and Silver coins NOT the best way to invest?

The British, who suffered greatly from IRA bombings and killings, damned McGuinness a ‘terrorist’ until he renounced violence and joined the political wing of the IRA. Many of his fellow Irish hailed him as a freedom fighter and patriot in the centuries-old resistance to British rule.

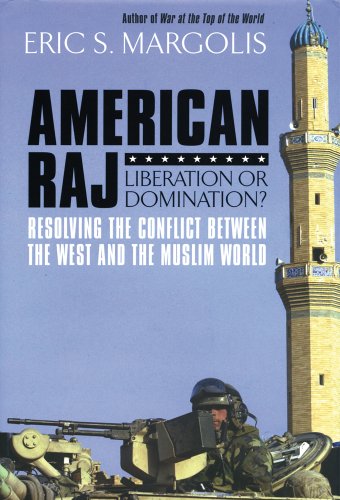

American Raj Liberatio...

Buy New $4.99

(as of 06:10 UTC - Details)

American Raj Liberatio...

Buy New $4.99

(as of 06:10 UTC - Details)

But I was also reminded of my dear, long-departed Auntie Mairead McCartney. She was a silver-haired, aristocratic Irish lady living in New York City who was very close friends with my mother. Auntie Mairead (as I called her) lived in a vast apartment on New York’s West End Avenue adorned by Tiffany lamps, Irish antiques, figurines of naughty Irish elves known as leprechauns, Victorian paintings, and rich Persian carpets.

Auntie Mairead shared the apartment with her elderly cousin, Matt Finnegan. They ran a clerical garb business catering to the New York Catholic Arch Diocese. There were boxes and boxes of nun’s and priest’s wear, rosaries, assorted crucifixes and piles of religious paraphernalia.

The apartment had a thick steel door secured by what is known in New York as a ‘police lock,’ a stout steel brace that fits into a special socket in the floor and then behind the main door lock. Once in place, it was near impossible to force the door open.

And well so. The steel door bore innumerable signs of efforts to force it. I recall lying in bed there at night, listening to would-be intruders trying to jimmy the lock or force the door frame. I was often parked at Mairead’s by my mother, an intrepid journalist who was one of the first female writers to cover the 1950’s Mideast. She interviewed Egypt’s Nasser and Sadat and Jordan’s King Hussein.

My mother discovered and reported that nearly a million Palestinians had been driven from the new state of Israel and were living in tents. This was when the official line was that Palestine, what became Israel, was ‘a land without people for a people without land.’

I recall many festive nights when Auntie Mairead, who was the queen bee of Irish society in New York City, gave parties for visiting Irish writers, poets, artists, and musicians. She would sit at her grand piano and thunder out lusty songs about Ireland’s quest for freedom and the lovely Scottish ‘Skye Boat Song.’

At the end of such evenings, our glasses would be refilled with Irish whiskey and we would cry out in unison, ‘Death to the British, Long live Ireland.’ I never admitted that I rather liked, even admired, the wicked Brits.

War at the Top of the ...

Buy New $4.99

(as of 06:10 UTC - Details)

Years later, I discovered why we lived behind a fortified door. It transpired that my beloved Auntie Mairead was a senior IRA leader in the New York City region and a scourge of the British. She was a chief IRA fundraiser who fuelled the Irish independence struggle. While American officials fulminated against so-called Mideast ‘terrorism,’ the then rampaging IRA was being chiefly funded from New York City and Boston.

War at the Top of the ...

Buy New $4.99

(as of 06:10 UTC - Details)

Years later, I discovered why we lived behind a fortified door. It transpired that my beloved Auntie Mairead was a senior IRA leader in the New York City region and a scourge of the British. She was a chief IRA fundraiser who fuelled the Irish independence struggle. While American officials fulminated against so-called Mideast ‘terrorism,’ the then rampaging IRA was being chiefly funded from New York City and Boston.

Not only that. My mother told me years later that dear Auntie was New York’s leading fence for hot rocks. In retrospect, I do recall Mairead once showing me one of the many cigar boxes she kept under her bed that was filled with lots of shiny little clear, blue and red stones. My child’s brain did not understand that this was a king’s ransom in jewels.

This was how my auntie financed the IRA. I would not be surprised, looking back, that behind the cartons of nun’s wear were boxes of Thompson .45 submachine guns and ammo. Even the holy saints sometimes used swords.

This was how my auntie financed the IRA. I would not be surprised, looking back, that behind the cartons of nun’s wear were boxes of Thompson .45 submachine guns and ammo. Even the holy saints sometimes used swords.

The Feds never caught on to Auntie, and we were never assaulted by British SAS commandos. Crooks and robbers never broke in our fortress. Auntie Mairead waged her little holy war against the British until some sort of peace finally came to Northern Ireland.

To this day – over half a century later – I still don’t know how living with my Auntie Mairead shaped me. I’ve always been a rebel by nature and resistant to authority. I feel sympathy for underdogs and the oppressed. I admire all those who fight for their freedom. Like traditional Japanese, I admire those who decide to fight even when they know the odds against them are overwhelming.

I guess I’ve become partly Irish by osmosis.