Although Plan B includes a wide spectrum of options, these three basic categories define three different purposes for having an alternative residence lined up.

We all have a Plan A–continue living just like we’re living now.

Some of us have a Plan B in case Plan A doesn’t work out, and the reasons for a Plan B break out into three general categories:

1. Preppers who foresee the potential for a breakdown in Plan A due to a systemic “perfect storm” of events that could overwhelm the status quo’s ability to supply healthcare, food and transportation fuels for the nation’s heavily urbanized populace.

Instant Access to Current Spot Prices & Interactive Charts

2. People who understand their employment is precarious and contingent, and they might have to move to another locale if they lose their job and can’t find another equivalent one quickly.

3. Those who tire of the stresses of maintaining Plan A and who long for a less stressful, less complex, cheaper and more fulfilling way of living.

The Fragility and Vulnerability of Highly Optimized Supply Chains

When Trucks Stop Runni...

Best Price: $51.13

Buy New $52.27

(as of 08:30 UTC - Details)

Many people are unaware of the fragility of the supply chains that truck in food, fuel and all the other commodities of industrialized comfort to cities. As a general rule, there are only a few days of food and fuel in a typical city, and any disruption quickly empties existing stocks. (Those interested in learning more might start with the book When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation.)

When Trucks Stop Runni...

Best Price: $51.13

Buy New $52.27

(as of 08:30 UTC - Details)

Many people are unaware of the fragility of the supply chains that truck in food, fuel and all the other commodities of industrialized comfort to cities. As a general rule, there are only a few days of food and fuel in a typical city, and any disruption quickly empties existing stocks. (Those interested in learning more might start with the book When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation.)

Most residents may not realize that the government’s emergency services are actually quite limited and that a relatively small number of casualties/injured people (for example, a few thousand) in an urban area would overwhelm services designed to handle a relative handful of the millions of residents.

Authorities can call up the National Guard to maintain order, but the government isn’t set up to provide food and fuel to millions of people stranded by a natural disaster or a “Black Swan” (unexpected disruption).

To reduce costs, supply chains and other essential systems have been stripped of redundancies–any break in the optimized flow has the potential to cripple the entire system. Since these highly optimized systems work so well most of the time, we don’t really understand the vulnerabilities that lurk just below the surface of “just in time” deliveries and other efficiencies.

This inherent fragility has long fueled interest in rural “bug-out” retreats, a topic I recently addressed in Having A ‘Retreat’ Property Comes With Real Challenges.

Where Do We Go When the Economy Falters?

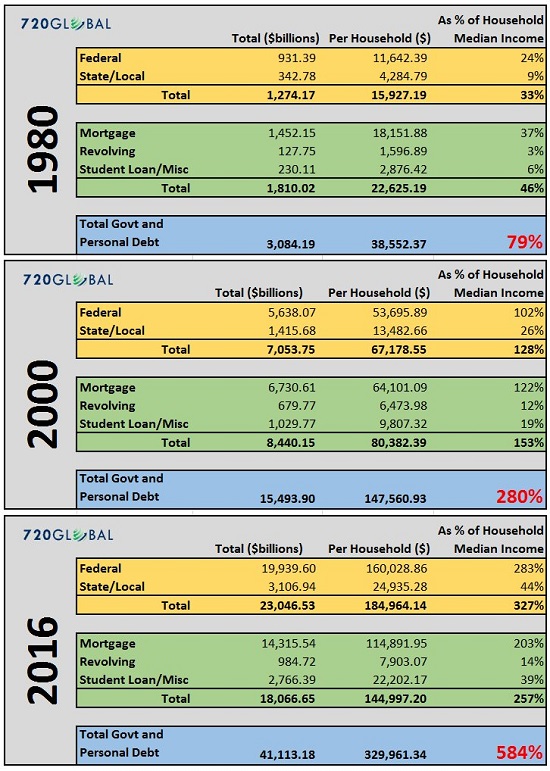

For the past eight years, US politicians and Federal Reserve authorities have attempted to repeal the classic business cycle of growth, stagnation, recession and renewed growth. It may appear they’ve succeeded, but the era’s slow growth has been sustained by unprecedented expansions of debt in the government, corporate and private sectors.

This extraordinary expansion of debt has been enabled by a decline in interest rates. Most observers with a sense of history view these extremes of debt expansion and near-zero interest rates as unsustainable and destabilizing:

(Source)

In other words, extending the expansion cycle by extreme policy measures cannot actually repeal the business cycle; rather, these policy extremes increase the likelihood that the eventual recession will be deeper and/or longer than it would have been absent the policy extremes.

Thus we can anticipate a recession of some sort, in which mal-investments and unpayable debts are liquidated and written off, and credit expansion (and the consumption that depends on it) slows or even reverses, as it did in the 2008-09 recession.

Employers must lay off employees when sales and profits fall, and as incomes fall, sales fall further, creating a feedback loop of mutually reinforcing declines in household income and spending.

When the music finally stops, many laid-off employees won’t be able to find a chair (i.e. another job). Without a job, most people can’t afford to remain in high-cost urban centers for long.

When the 2000 recession gutted employment in the San Francisco Bay Area, 100,000 people moved away.

Recent immigrants to wealthy metro areas have the option of returning home to the village or town they’d left to seek work in the city. Many immigrants from south of the border have invested their earnings in building new homes in their villages of origin. When the economy north of the Rio Grande falters, they can return to the home they built when their incomes were high.

In China, many of the urban workers laid off in slow periods return to their villages, where there is a source of food (farms) and a roof over their head (the family home).

Today’s “rootless Cosmopolitans” (urban-dwelling Americans) typically lack a village they can return to in hard times. So a common Plan B is to seek an equivalent low-cost place to retreat to in recessions.