By Dr. Mercola

When you go to the restaurant or grocery store, food fraud is probably the last thing on your mind. In his fantastic book, “Real Food/Fake Food: Why You Don’t Know What You’re Eating and What You Can Do About It,” Larry Olmsted, an investigative journalist and food critic, sheds much-needed light on this important topic.

It’s loaded with solid information revealing just how prevalent food fraud actually is — and offers helpful guidance on how to make sure you’re actually getting what you’re paying for.

“I’ve been writing about food and travel for a wide variety of newspapers and magazines around the world for over 20 years,” he says. “In my travels or whenever I go someplace, I try to eat what the locals eat, whatever the specialties are.

I came upon a few cases … where I would come back and try to replicate those foods either on my own or in restaurants in the United States, and it never really tasted right or looked right.

Particularly, in the case of Kobe beef. I did a little research into why I couldn’t get any good Kobe beef here. I learned quickly there’s no [real] Kobe beef here. All the restaurants pretending to serve Japanese Kobe beef were lying; every single one in the country.

I wrote a story about that for Forbes. It got a phenomenal response and I ended up just continuing to research this topic and it evolved into this book.”

Click HERE to watch the full interview!

Visit the Mercola Video Library

Food Fraud Is Massively Prevalent

Real Food/Fake Food: W...

Best Price: $2.00

Buy New $6.99

(as of 06:25 UTC - Details)

Real Food/Fake Food: W...

Best Price: $2.00

Buy New $6.99

(as of 06:25 UTC - Details)

There’s a general impression that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is policing and regulating food fraud, but in reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

The main focus of the FDA is the ingredient label, making sure it’s accurate. They also track food-related disease outbreaks. The agency does not, however, dedicate any significant amount of resources to the safety and integrity of the foods you eat every day.

One of the most pervasive areas of fraud is the seafood industry. It’s quite disheartening, as seafood (when fresh and free of toxins) is one of the healthiest foods on the planet that we all should be eating more of.

Yet Olmsted’s investigation reveals the likelihood of actually getting what’s stated on the menu when you eat at a restaurant is miniscule.

“You’re right, people should be eating seafood,” Olmsted says. “It’s probably the healthiest source of animal protein out there. There’s lots of seafood that is good for you. It’s just a matter of making sure you’re getting what you’re buying. That’s really the issue.

A great example is salmon. The American people have demonstrated — both in their buying habits and when polled — that they greatly prefer wild caught salmon to farmed, even if it’s more expensive.

The problem is, sometimes you buy wild-caught salmon, you pay a premium for it, and you’re still getting farmed salmon.

If your goal was to avoid the things that are used in aquaculture, which include vaccines and antibiotics, then you’re really getting doubly defrauded. You’re getting ripped off financially and you’re getting ripped off, at least from your perception, of what’s healthy and what’s not.”

Red Snapper — The Most Defrauded Fish Species of All

Swapping wild for farmed is not the only problem plaguing the seafood industry. Species substitution is also rampant, with red snapper being the most defrauded fish species of all.

It’s also one of the most expensive, in part because it tastes great, and secondly, because real red snapper is always wild caught. There’s no such thing as commercially farmed red snapper. Alas, if you order red snapper in a restaurant, chances are you’ll get a completely different fish served to you.

Almost always, it’ll be an inexpensive farmed fish like tilapia, probably imported from Southeast Asia, and probably farmed under dubious conditions.

“This is not something that happens once in a while. This is something that happens with red snapper more than 9 out of 10 times. You could go out for a week and order red snapper every day and there’s a good chance you’re never going to get it,” Olmsted warns.

How to Avoid Being Defrauded When Buying Seafood

Wild Planet Wild Sardi...

Buy New $27.69 ($0.52 / Ounce)

(as of 11:55 UTC - Details)

Wild Planet Wild Sardi...

Buy New $27.69 ($0.52 / Ounce)

(as of 11:55 UTC - Details)

Olmsted’s book provides a number of excellent tips to assure you’re not being defrauded, including the following:

•Buy your fish from a trusted local fish monger.

•When buying fish from grocery stores or generic big box retailers, look for third-party labels that verify quality.

◦The best-known one is the Marine Stewardship Council (their logo features the letters MSC and a blue check mark in the shape of a fish). MSC has auditors who certify where the fish came from and how it got to you.

◦If the fish is farm-raised, look for the Global Aquaculture Alliance Best Practices symbol.

◦Alaska does not permit aquaculture, so all Alaskan fish is wild caught. They have some of the cleanest water and some of the best maintained and most sustainable fisheries.

To verify authenticity, look for the state of Alaska’s “Wild Alaska Pure” logo. This is one of the more reliable ones, and it’s a particularly good sign to look for if you’re buying canned Alaskan salmon, which is less expensive than salmon steaks.

Why Restaurant Shrimp Are Best Avoided

My favorite seafood, bar none, is shrimp. But Olmsted’s book has now convinced me to avoid shrimp whenever I eat out. Restaurant shrimp is virtually 100 percent guaranteed to be from poorly policed farms in Southeast Asia.

“Shrimp is the single most consumed seafood in the United States. We eat more pounds of shrimp than any other fish. That’s a fairly recent phenomenon. I know when I was growing up, shrimp were … considered more of a celebratory, special event food.

You’d go out to a fancy steakhouse and you’d have a shrimp cocktail, and that would be a splurge. There was no perception that you would go to some fast food restaurant and pay 9.99 and get all-you-can-eat popcorn shrimp. As we adopted the model that shrimp should be cheap and readily available, the only way to provide that was to farm them very cheaply, mostly in Southeast Asia. There are a lot of problems with that.

One is where they locate the shrimp farms. They typically clear cut mangroves, which are nature’s filtration system and defense against tsunamis. It’s really bad for the environment. A lot of waste and chemicals dumped directly to the ocean …

[There’s] well-documented use of slave labor in production of farmed shrimp. It’s kind of a triple whammy. Bad for us, bad for the world, bad for the people involved — and the shrimp frankly doesn’t taste very good … I do like wild-caught shrimp from the Gulf of Mexico.

The problem again being that sometimes you go to the store and buy a bag that says “wild-caught shrimp” from the Gulf of Mexico, and it simply is not. There’s a lot of fraud with shrimp.”

Farmed Shrimp Is Often Toxic

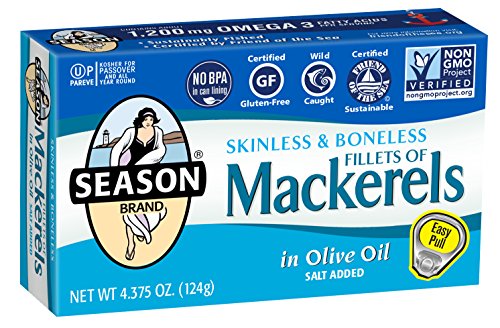

Season Fillets of Mack...

Buy New $27.99

(as of 12:30 UTC - Details)

Season Fillets of Mack...

Buy New $27.99

(as of 12:30 UTC - Details)

In 2015, the FDA had a record number of import refusals for shrimp. This is when shrimp is tested and found to contain unacceptable contaminants, such as banned antibiotics or elevated levels of toxins.

Some of the antibiotics used in shrimp farming are not allowed in American food production because they’ve been deemed carcinogenic. Olmsted recommends avoiding shrimp in restaurants unless you’re absolutely convinced the shrimp were indeed caught in the Gulf of Mexico.

But, while Olmsted will eat such shrimp, others are concerned about the challenge of potential contamination from the oil spill and subsequent use of Corexit, a chemical that is more toxic than the oil itself. So if you choose to regularly consume Gulf shrimp I would suggest getting it tested.

“If I’m in a seafood restaurant in, say, the Gulf coast in Mississippi or Alabama or the Florida Panhandle, and I’m fairly certain that when they say they’re buying their fish or shrimp locally from the fishermen, that they’re telling the truth … I’ll make that leap. Usually, again, you can tell the shrimp tastes better.

Shrimp is something that is never going to be really cheap. Even if you’re buying it at the dock, there’s a sort of a minimum price per pound (typically in excess of $18 per pound.) If you see a deal at a restaurant that seems too good to be true, it almost certainly is.

I’ll eat shrimp that I honestly believe comes from the Gulf of Mexico or off the Atlantic Coast of Florida. The Carolina State has pretty good shrimp. Up where I live in New England, the Gulf of Maine produces excellent shrimp. But for the last two years, they’ve set the quota at zero to allow the stocks to recover, so there is no shrimp from the Gulf of Maine.

It’s very difficult to find farmed shrimp that’s produced in the United States. If I saw it, I would actually buy it because the shrimp farming in the U.S. is very clean. But it’s not price competitive. It’s still sort of an experimental stage. It’s almost impossible to buy domestically farmed shrimp,” Olmsted says.

Beware of Sushi

Sushi is another seafood niche that is rife with fraud. Olmsted suggests circumventing fraud by frequenting the more expensive sushi restaurants, such as Masa in New York and Nobu in Las Vegas, that fly in freshly-caught fish. The drawback is you’ll be paying top dollar. If you want to eat at your local sushi place, opt for nigiri sushi or sashimi where you can at least see some of the fish.

Also, beware that tuna is typically best avoided due to contamination issues. It’s a large fish that tends to bioaccumulate toxins like PCBs and mercury. Anyone consuming tuna needs to be aware of that and take proactive measures — such as taking a handful of chlorella tablets with your meal — to counteract it.

Smaller Fish Are Typically a Safe Bet

Some of the healthiest seafood are the smallest fishes, such as anchovies, sardines, and mackerel, which are typically sold in cans. The good news is these are far less prone to fraud, in part because they’re less popular and therefore less expensive, and in part, because they’re packed whole. You cannot chop up another fish to make it look like a sardine, for example.

ZOE Organic Extra Virg...

Buy New $24.99 ($0.49 / Fl Oz)

(as of 07:00 UTC - Details)

ZOE Organic Extra Virg...

Buy New $24.99 ($0.49 / Fl Oz)

(as of 07:00 UTC - Details)

“There’s less fraud whenever something is inexpensive because there’s less money to be made substituting a lower quality. In fact, with seafood in general, if you go into a restaurant and you see something like a spiny dogfish on the menu, you’re probably safe.

There’s no market in faking spiny dogfish or catfish or a lot of the inexpensive fish. It’s always the pricey ones. These small fish, they’re whole. They’re inexpensive. They’re fairly plentiful, and the selection in cans and tins and jars has gotten much better in recent years.

I buy a lot of those products from Spain. Spain is really known for the quality of its canned seafood … [A]void the [fish packed in] olive oil, because when it’s used as packaging, it’s incumbent upon the producer to use the cheapest olive oil they can get.”

Olive Oil Fraud

Olive oil is a $16 billion-a-year industry fraught with fraud. Tests reveal anywhere from 60 to 90 percent of the olive oils you find in grocery stores and restaurants are adulterated with cheap, oxidized, omega-6 vegetable oils, such as sunflower oil or peanut oil, that are pernicious to health in a number of ways.

“Italy makes some delicious extra-virgin olive oil and they make some very good real extra-virgin olive oil. The problem is a lot of what is exported from Italy is not their best product,” Olmsted says. “People associate olive oil with Italy … The thing that they look for most is that the oil comes from Italy. But coming from Italy is not the same as being made in Italy.

Italy is the world’s largest exporter of olive oil, but they’re also the world’s largest importer of olive oil. They buy up oil from all over the Mediterranean basin — from Tunisia, Syria, Morocco, Spain — blend it, bottle it. Often it’s labeled “bottled in Italy,” which is technically true. It was shipped to Italy and put into bottles, but it’s not Italian olive oil. When people buy that, they’re relying on some sort of myth of Italian quality.

Italy doesn’t even produce enough extra-virgin olive oil to meet its own domestic demand. While you can get very good olive oil from Italy, it’s trickier than from some other countries … What people need to understand about olive oil is that it’s essentially closer to fresh-squeezed fruit juice than it is to most of the other oils we’re familiar with … As a result, olive oil has a fairly short shelf life compared to other oils.“

How to Identify High-Quality Olive Oil

Part of the problem is that olive oil is shipped by boat, which takes a long time. Then it’s stored and distributed to grocery stores, where the oil may sit on the shelf for another several months. Moreover, the “use by” or “sell by” date on the bottle really does not mean a whole lot, as there’s no regulation assuring that the oil will remain of high quality until that date.

The date you really want to know is the “pressed on” date or “harvest” date, which are essentially the same thing because olives go bad almost immediately after being picked. They’re pressed into olive oil basically the same day they’re harvested. High-quality olive oil is pressed within a couple of hours of picking. Poorer quality olive oils may be pressed 10 hours after the olives are picked.

Ideally, the oil, based on the “pressed” or “harvest” date, should be less than 6 months old when you use it. Unfortunately, few olive oils actually provide a harvest date.

As for olive oil in restaurants, more often than not, the olive oil served for bread dipping is typical of very poor quality and is best avoided. For more information about olive oil — how it’s made and what constitutes extra-virgin olive oil, please listen to the full interview, or read through the transcript, where Olmsted goes into more details about pressing, grading, and testing.

What I really enjoyed about Olmsted’s chapter on olive oil is that he explains how to make your own, and I just happen to have olive trees, so I will probably start making my own freshly-pressed olive oil.

Where to Find the Best Olive Oil

Surprisingly, the big box stores actually do a better job with their supply chain of most foods, including olive oil and seafood.

“People are really surprised to hear that I feel more confident buying my seafood or even olive oil at a BJ’s or Costco than my local supermarket,” Olmsted says. “I think the best way to buy olive oil is at any store that will actually let you taste it … [such as] gourmet stores or specialty retailers …

Because once you taste good olive oil, you can never go back to the bad stuff. It’s pretty clear when you taste it and smell it that it’s fresh, that it’s fruity, that it’s a whole different ball game. That’s the best way to buy it. Another thing is to look at some other countries that people don’t really associate so much with olive oil, but do a great job. I’m a big fan of Australia.

Most of the experts I talked to say, across the board, [Australia has] the best, most reliable quality. Australia also has separate legal standards from what most of the rest of the world uses for olive oil, which are considerably stricter, the testing and the grading. I like a lot of the new world olive oils: California, Chile, South Africa.”

Parmesan — One of the Most Wholesome Cheeses You Can Get

Parma, Italy, is world-famous for food. This is where Parmesan cheese and prosciutto di Parma comes from. Parmalat, the single largest Italian food company, is also based there, as is Barilla Pasta, the largest pasta maker in the world.

Parmigiano-Reggiano, “the king of cheeses,” is made today as it was 800 years ago. It’s also one of the most strictly regulated, most wholesome, purest foods you can buy, according to Olmsted. The law even dictates where the cattle are allowed to graze. They’re all grass-fed cows that are not allowed to graze in fields where fertilizer or pesticides are applied.

“You know that the milk that comes from these cows is as pure as it could be. It’s like the milk was 800 years ago. It’s not chemically altered in any way,” he says. “Rules for Parmigiano-Reggiano dictate that the cheese making process begin immediately within two hours of the cow being milked.

You got fresh, pure, wholesome milk going into the cheese. The only other ingredients that can be used to make the cheese are salt and rennet, which is a digestive enzyme that makes the cheese curdle … Then it’s aged. It’s tested, every single wheel, for quality before it’s sold. It’s just a wonderful cheese that guarantees the buyer of purity.”

Fake Parmesan Cheese Is Totally Legal in the US

Buyer beware, however, as FDA regulations make it legal to sell fake Parmesan cheese. As noted by Olmsted, there are two separate problems with the Parmesan cheese sold in the United States. One is the pre-grated cheese, which typically contains added cellulose, a plant fiber, which is added to prevent clumping.

The industry can add 2 to 4 percent cellulose to the cheese to achieve that end, but because cellulose is cheaper than cheese, and the FDA does not specify an upper limit for cellulose in cheese, most have taken to adding far more than needed in order to boost their profit margins. Lab tests done by Bloomberg and Inside Edition earlier this year revealed that some pre-grated Parmesan cheeses sold in the U.S. contained more than 20 percent cellulose! As Olmsted says:

“You’re paying for cheese and you’re getting plant fiber … The bigger problem to me — and this isn’t just Parmesan cheese, this is Gruyere and Manchego and a lot of the great European cheeses — is that we have almost no trademark protection in the United States allowed for what are known as geographically indicated foods. The best example of which would be champagne.

These are foods that people associate with coming from a particular place. In the rest of the world, Parmesan cheese legally means this one cheese that can come from Parma, made in a certain way. But in the United States, you can call anything you want Parmesan cheese and it’s legal. You can call anything you want Gruyere and it’s legal.

Very few Americans realize that we produce a lot of champagne domestically that’s labeled “champagne.” People say to me all the time, ‘I thought champagne had to come from France.’ It should, but it doesn’t in the United States. It’s the same problem that got me started with the Kobe beef. It’s legal for restaurants here to call anything they want Kobe beef. Americans see all these names and assume that they’re getting these high-quality imported foods and they’re simply not.”

More Information

Olmsted’s book, “Real Food/Fake Food: Why You Don’t Know What You’re Eating and What You Can Do About It,” offers a truly eye-opening view of our food system, giving you a solid base of information to make wise food choices. He not only exposes the fraud but also provides practical tips and recommendations for finding the real McCoy.

We covered three of the most frequently defrauded foods — seafood, olive oil and Parmesan cheese — but there are dozens of others as well. If you found this interview and discussion valuable, I would highly recommend picking up a copy of his book to learn more about the food fraud he exposes.

“Fake, fraudulent, misleading, adulterated foods are a $50 billion-a-year industry,” Olmsted says. “[It] reaches into basically every sector of the supermarket, from honey and coffee and staples like juice, to the specialty foods like Kobe beef and wild Alaskan salmon.

But I don’t want people to be scared to eat. Sometimes I do these interviews and everybody’s shocked at some of the statistics. I want people to love their food, to eat delicious food that’s also healthy for you. I devoted a lot of the book to that. That’s why I give such specific tips so that the consumer could just be better armed. Information is certainly your best resource.”