Growing up in L.A. in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I certainly had my fill of hippies (and then some). And I have to say, the hippies of that time weren’t all bad. Slovenly, spoiled, self-righteous, sure. But some of their rhetoric was totally on point. “Always question yer assumptions, man. Question everything, little dude,” I can still hear the flea-bitten friends of my long-haired, war-protesting cousin advising me between bong hits.

In a way, I long for the hippies of old. Because if there’s one thing today’s leftists don’t do, it’s question their assumptions. Of course, it was easy for 1969 leftists to preach the gospel of assumption-questioning. They were born into the world in which American society’s prevailing assumptions were essentially conservative. “Work hard and you can succeed.” “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” “Good grooming is essential for a successful job interview.”

Like, Squaresville, man.

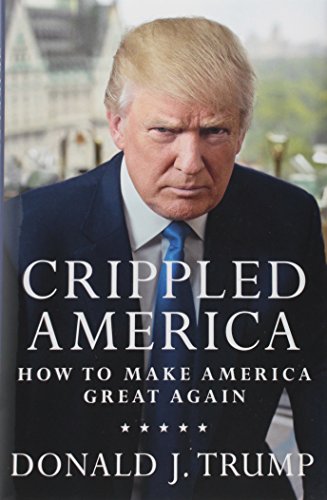

Crippled America: How ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $8.97

(as of 03:40 UTC - Details)

Crippled America: How ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $8.97

(as of 03:40 UTC - Details)

Now that the left has established its dominance over such influential institutions as academia and the press, assumption-questioning has gone the way of the 8-track. It’s truly astounding to me the extent to which the left doesn’t question its assumptions these days. One of my favorite examples is the beloved myth of “Hispanic blood.” Under current affirmative-action policies, anyone—anyone—who has Hispanic ancestry qualifies for preferential treatment. As law professor David Bernstein disapprovingly points out, affirmative-action benefits in college admissions can be given to “direct descendants of Spanish conquistadors, their indigenous victims, African slaves, immigrants from anywhere in the world, or any combination of these,” as well as a “child who has one set of grandparents descended from the Mayflower and another set of mixed-race Puerto Rican grandparents who arrived in New York City in the 1930s,” and even an “Argentinean child of German refugees from (or perpetrators of) Nazism.”

Basically, if you have any ancestry that is defined as “Hispanic,” leftists define you as handicapped and therefore in need of special help getting into college or finding a job. By the left’s definition, the blond, blue-eyed son of a Chilean millionaire needs help, but a dark-featured, dirt-poor Appalachian kid doesn’t. I used to enjoy tormenting leftists with what I call my “Brancato test.” Lillo Brancato Jr. is the actor best known for playing a Mob-connected Italian kid in the Robert De Niro film A Bronx Tale, and a Mob-connected Italian kid on The Sopranos. I would show leftists Brancato’s photo and ask if he would need special affirmative-action assistance to get into college. “Oh, no, of course not!” was always the reply. “Italians are white; that privileged kid needs no preferential treatment.” I’d then inform my mark that Brancato is actually Colombian, not Italian (he was a Colombian orphan adopted by Italian parents), and immediately the answer would change: “Oh dear God, of course, that poor young oppressed Hispanic boy needs affirmative action! Add points to his SAT score ASAP!”

Trump: The Art of the ...

Best Price: $5.63

Buy New $8.22

(as of 10:41 UTC - Details)

Trump: The Art of the ...

Best Price: $5.63

Buy New $8.22

(as of 10:41 UTC - Details)

Same kid, same face. All that changed was where leftists thought he came from. To leftists, “cryptos panics” like Brancato are just as deserving of victim-group status and just as entitled to affirmative action as Kalahari Bushmen. It’s as if leftists are saying that evil white “gatekeepers” at universities and corporations can smell the blood of a Hispanic and therefore even Hispanics who don’t look Hispanic still need aid and protection.

Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of a Mexican.

“Hispanic blood” is just one example of assumptions the left never feels the need to explain (Professor Bernstein’s masterful takedowns at SCOTUSblog and the Volokh Conspiracy deserve to be read in full). Another, a less-explored bit of leftist nonsense is what I’ve christened the “Bubbafly Effect.” The name is a play on the butterfly effect, which is understood in popular culture as the principle by which something as minor as a butterfly flapping its wings might lead to something as major as a hurricane-force wind. The butterfly effect was first codified by MIT meteorologist Edward Lorenz in a paper entitled “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” Lorenz’s goal was to explore “chaotic behavior in the mathematical modeling of weather systems.”