The public memory of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement has been shaped by iconic images of state-licensed violence – peaceful protesters being beaten and otherwise abused by police for exercising the right to seek redress of grievances. The civil rights movement began as an effort to remove government impediments to individual liberty. By 1964 it had become a concerted effort to subject all private functions to government scrutiny and regimentation.

According to the custodians of acceptable opinion, the campaign to compel acceptance of same-sex marriage is the legitimate heir to the Civil Rights movement. The symbolic image of the contemporary movement could be a photograph of a shell-shocked Crystal O’Connor, manager of the family owned Memories Pizza restaurant in Walkerton, Indiana, after the business became the focal point of an orchestrated campaign of mass vilification.

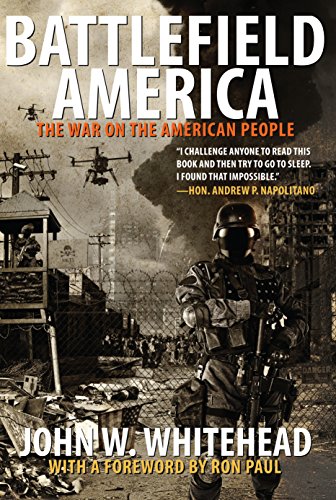

Battlefield America: T...

Best Price: $10.95

Buy New $18.80

(as of 10:15 UTC - Details)

Battlefield America: T...

Best Price: $10.95

Buy New $18.80

(as of 10:15 UTC - Details)

Her offense was to speak favorably of Indiana’s recently enacted – and hastily modified – religious freedom act. The advertised purpose of that measure was to protect the rights of business owners to decline commercial opportunities that would require them to compromise their values.

In response to a contrived question by a TV reporter seeking to engineer a controversy, O’Connor said that her company would decline an invitation to cater a same-sex wedding. She also made a point of saying that the store would accept paying customers of all varieties – but this distinction is too subtle for people in the throes of collectivist pseudo-outrage.

O’Connor and her family, who had never injured a living soul or expressed any intention to do so, underwent a baptism in bile and were ritually execrated as proponents of “hate.”

Thankfully, a counter-movement quickly coalesced to raise funds for the besieged – and thoroughly befuddled – Christian business owners, who had no agenda apart from tending to their customers. They hadn’t gotten the message that their business, as a “public accommodation,” was not theirs to operate as they see fit.

Many businesses still display a sign asserting their right to discriminate, which is an indispensable element of property rights: “We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.” Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which deals with “public accommodations,” was designed to nullify that right.

In announcing his opposition to the Act, Senator Barry Goldwater emphasized the latent totalitarianism of that provision:

“To give genuine effect to the prohibitions of this bill will require the creation of a Federal police force of mammoth proportions. It also bids fair to result in the development of an ‘informer’ psychology in great areas of our national life – neighbors spying on neighbors, workers spying on workers, businessmen spying on businessmen, where those who would harass their fellow citizens for selfish and narrow purposes will have ample inducement to do so.”

“These, the Federal police force and an ‘informer’ psychology, are the hallmarks of the police state and landmarks in the destruction of a free society,” concluded Goldwater, whose peroration proved to be prophetic.

The nation-wide convulsion of collectivist rage triggered by enactment of the Indiana religious freedom act illustrated that “civil rights,” as currently defined, requires the immediate punishment of any business owner who exercises the right to refrain from commerce. Yes, self-styled proponents of “tolerance” can succumb to the temptations of punitive populism, just like their counterparts on the Right.

An even more compelling illustration of the totalitarian mindset that typifies what is now called “civil rights” was offered by Idaho’s HB 2, more commonly known as the “Add the Words” bill. If it had been enacted by the state legislature, HB 2 would have added “sexual orientation” of various kinds to the state’s Human Rights Act as a protected category with regard to discrimination in employment and “public accommodations.” It also would have explicitly criminalized – perhaps for the first time anywhere in the Soyuz – the act of reserving one’s right to refuse service.

Section 67-5909 (5) (b) of the legislation would have made it a “prohibited act” for “a person” to “print, circulate, post, or mail or otherwise cause to be published a statement, advertisement, or sign which indicates that the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages of a place of public accommodation will be refused, withheld from, or denied an individual or that an individual’s patronage of or presence at a place of public accommodation is objectionable, unwelcome, unacceptable, or undesirable.”

If HB 2 or a future measure employing the same language were to be enacted, a business owner who posted the “right to refuse” sign could not only be sued, but dragged away from his property in handcuffs. A critic of the measure could likewise find himself being prosecuted for publishing a letter to the editor, a Facebook post, or a blog comment urging business owners to exercise the right of refusal.

Punishing the peaceful expression of such opinions would be justified, according to the civil rights commissariat, because government has a “compelling interest” in preventing discrimination – even at the expense of individual liberty.

The incantation “compelling government interest” is a useful illustration of the fact that the lexicon of federal law enforcement is an inexhaustible, self-replenishing reservoir of deceit.

Most people exposed to this masterpiece of semantic engineering hear what its designers intended – a claim that the government is compelled to do something – rather than what it actually means – that the government is claiming the authority to compel individuals to do something.

This term of art litters court orders and bureaucratic edicts through which our rulers impose economic and cultural alterations that are intended to remold society nearer to their hearts’ desire.

As an abstract fiction without body, parts, or passions, the state cannot have a legitimate “interest” in anything. Indulging, for a moment, the contrary view, the state’s interest in self-preservation would always dictate the expansion of power, and the corresponding curtailment of liberty. This shouldn’t be considered surprising once it’s understood that the “compelling state interest” doctrine had its origins in the Supreme Court’s 1944 decision Korematsu v. United States – which upheld the mass internment, in military custody, of Japanese-Americans who had broken no law.

Fred Korematsu had committed no crime apart from defying an edict that expropriated him – through race-specific banishment from a “military exclusion zone” that encompassed his property.

Clothing the sentiment of “sucks to be you” in the rarefied language of jurisprudence, the Supreme Court upheld Korematsu’s federal conviction as an exercise of vital wartime powers by “properly constituted military authorities” with a congressional mandate. The Warren Court would later redeploy that wartime doctrine to facilitate the federal government’s domestic war against “discrimination.”

The Japanese relocation camps were filled with people whose homes, farms, personal effects, businesses, and individual liberty had been taken from them by people acting in the name of what would later be called a “compelling government interest.”

The Japanese relocation camps were filled with people whose homes, farms, personal effects, businesses, and individual liberty had been taken from them by people acting in the name of what would later be called a “compelling government interest.”

Among the innocent people who suffered this inexcusable mistreatment was the family of a young Japanese-American named George Takei, who would later become universally beloved for his portrayal of the heroic helmsman Hikaru Sulu of the Starship Enterprise.

More recently, Mr. Takei has become one of the most prominent supporters of the ongoing effort to compel acceptance of gay marriage through both social pressure and government coercion. Last January 30, Mr. Takei delivered the keynote address during the 5th Annual Fred T. Korematsu Day observance, most likely ignorant of the fact that he’s promoting the same evil doctrine that led to his childhood dispossession.