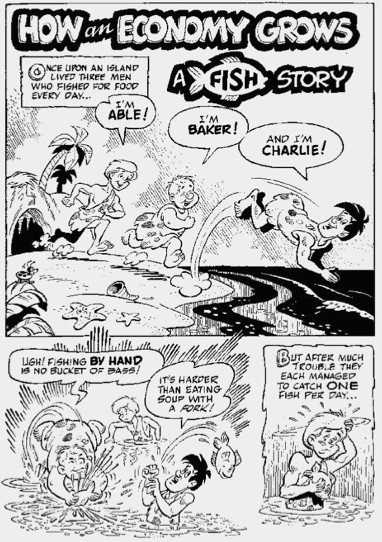

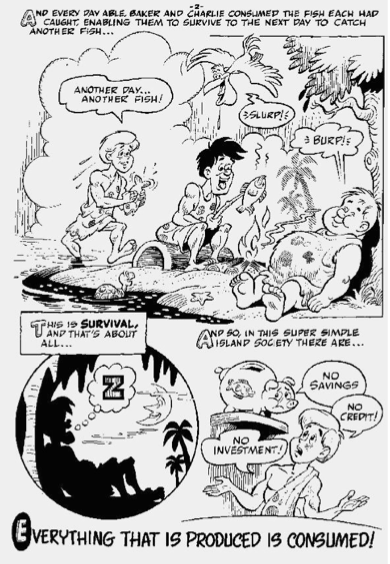

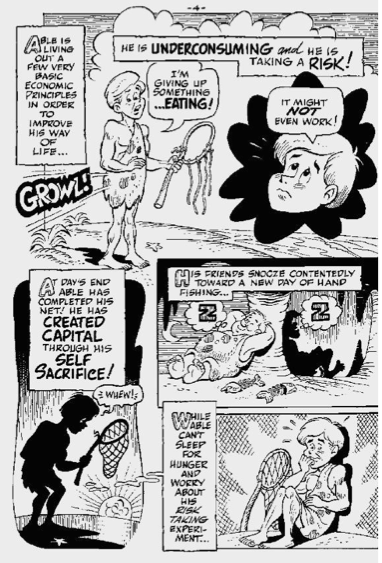

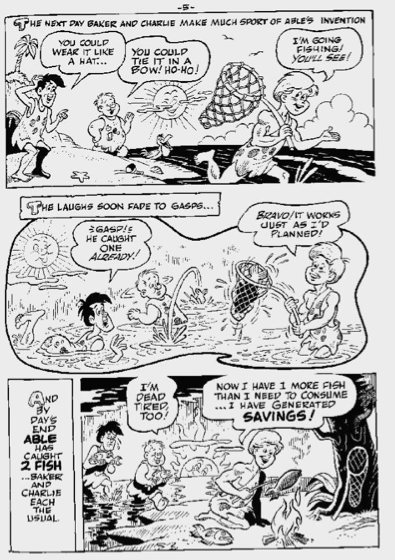

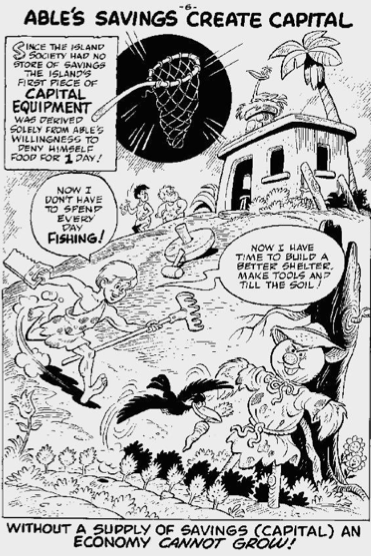

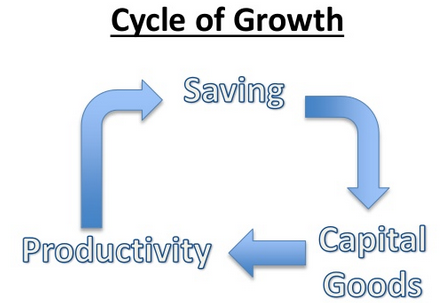

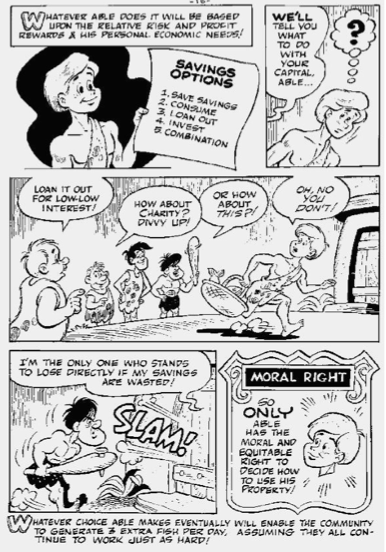

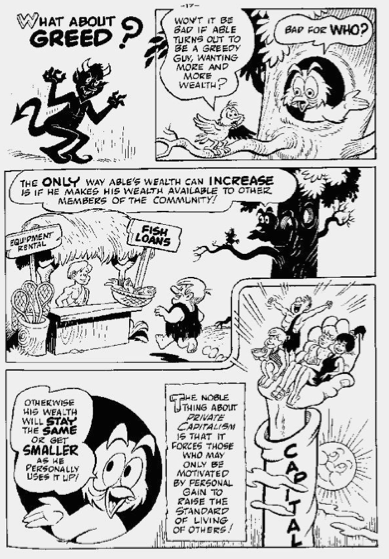

Back in the 1980s, Irwin Schiff, anti-tax activist, political prisoner, and father of free-market pundit Peter Schiff, wrote a marvelous comic book titled How an Economy Grows and Why It Doesn’t, which teaches economic principles through a light-hearted story. The comic starts with three islanders—Able, Baker, and Charlie—who live off of fish, which they catch in the sea. They have no tools to aid them, so they must fish with their bare hands. Fish, to the islanders, is a consumers’ good: something that is used to directly pursue their goals (in this case, the goals of satisfying hunger and not starving). But, fish can only be a consumers’ good when it is ready for consumption. The fish do the islanders no good while they are still swimming in the sea. So the islanders must engage in production. They must produce the product of “fish on a plate,” which is, to be exact, the true consumers’ good, and not simply “fish” per se. To produce “fish on the plate,” the islanders must use productive resources, or factors of production. One factor the islanders must use is their own labor. In this case, their labor is the act of fishing: using their eyes to spot the fish, and their hands to grab them. Another factor they must use is land, or natural resources: in this case, “fish in the sea.” “Fishing labor” + “fish in the sea” = “Fish on the plate.” Using only their bare hands, the islanders can only produce one fish per day, which is very low productivity. As Schiff writes, with such low productivity, “This is survival and that’s about all.” It is a state of extreme poverty. The islanders have little time for leisure, or to produce anything else they might want to enjoy. They are also extremely vulnerable. What if they get sick, or break their hand? A single bad week of fishing could mean starvation. Life with such low productivity, is life on the brink. Like a Disney princess, Able dreams of “something more”. He’s tired of being poor, and wants to somehow improve his living standards. He comes up with the idea of building a net to use to catch fish faster (boost his productivity). The net is a third kind of factor: a capital good, or produced factor of production. Producing a net also requires factors, including natural materials (land), like sticks and vines, and net-building labor. Building the net would take a whole day. That would be a whole day that Able wouldn’t be fishing. His labor is scarce; it cannot be dedicated to both fishing and net building at the same time, and so it must be economized: dedicated to one and not the other. And if Able doesn’t fish, he goes hungry for that day. Building the net would require sacrifice: delaying consumption. Able must decide between two different production methods. Does he stick to hand fishing, or does he switch to net fishing? He must consider the upsides and downsides of each. The upside of hand fishing is that it has a short period of production. Able starts production, and then gets to eat later that very same day. The downside is its low productivity, and Able’s resulting chronic state of poverty. The upside of net fishing is its higher productivity, which is two fish per day according to the comic; but for illustrative purposes, let us change the productivity of net fishing to three fish per day. The downside of net fishing is that it has a longer period of production at first. It takes one day to make the net, and then another day to use it. So, Able would start production, and only get to eat two days later. Able is at a crossroads. He can either stay mired in primitivism, or he can rise above it. Rising above economic primitivism is often considered simply a matter of technology. However, simply having the idea of, and the know-how for, producing a net, is not an immediate, costless benefit for Able. It would be costless if it were simply a matter of choosing between “1 fish today” and “3 fish today.” Of course greater is automatically better than less, other things being equal. But other things are not equal: a difference regarding time is an essential consideration here. It is not simply greater vs. less; it is “greater and later” vs. “less and sooner.” So the decision for Able whether to adopt the “net fishing” technology involves a trade-off: an “exchange” he deliberates over in his mind. Will he give up the “less and sooner” yield that comes with hand fishing in exchange for the “greater and later” yield that comes with net fishing? The answer to that depends on Able’s personal time preference, or the premium he places on the immediacy with which he achieves his ends: the importance of “soon”. The lower someone’s time preference is, the more willing someone will be to delay consumption. And the higher, the less. For example, as the comic later indicates, the time preferences of Baker and Charlie are too high for them to make the net. Giving up eating today is too great a sacrifice for them, even if it would mean being able to eat three times as much tomorrow. If net fishing were more productive, that might have sweetened the deal enough; i.e., if the net netted five times as much, they might have been willing to wait. Their time preferences are not infinitely high. But they are not low enough to embark on this particular capital project. But Able’s time preference is low enough, so he is willing to delay consumption, produce the capital good, and increase his productivity. Morevoer, the day after his first big net-aided catch, he has enough extra fish to not have to fish all day, because he can subsist on what he has already caught. Instead, he can spend the day creating even more capital goods to raise his productivity even higher. For example, he makes a rake to use to farm carrots. And he can use the additional yield from carrot farming to support even more capital accumulation. As he becomes ever more productive, he can also afford to devote more resources toward leisure and comfort as well. Thus, Able’s low time preference puts him in the fast track of an ascending spiral: a virtuous “Cycle of Growth.” Saving (delaying consumption) supports more capital goods, which boosts productivity, which creates more to save, and around he goes. With every lap around this loop, he becomes wealthier, as both his capital stock and living standards increase. And with every lap, he inches ever further away from the brink and toward greater security and peace-of-mind. A bad week of production becomes merely a bummer, and not a catastrophe. This Cycle of Growth, by the way, is the way living standards rise in a complex market economy as well. But then others on the island start getting their own ideas about what Able should do with his newly abundant resources. One man says, “Divvy up.” This is an example of the envy-based egalitarian ethos that has afflicted peoples throughout history and pre-history, keeping them poor and primitive. As Murray Rothbard wrote: In fact, the primitive community, far from being happy, harmonious, and idyllic, is much more likely to be ridden by mutual suspicion and envy of the more successful or better favored, an envy so pervasive as to cripple, by the fear of its presence, all personal or general economic development. The German sociologist Helmut Schoeck, in his important recent work on Envy, cites numerous studies of this pervasive crippling effect. Thus the anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn found among the Navaho the absence of any concept of “personal success” or “personal achievement”; and such success was automatically attributed to exploitation of others, and, therefore, the more prosperous Navaho Indian feels himself under constant social pressure to give his money away. Allan Holmberg found that the Siriono Indian of Bolivia eats alone at night because, if he eats by day, a crowd gathers around him to stare in envious hatred. If every time someone saves more, he is pressured to relinquish his “excess wealth,” that can only discourage savings. And knocking out savings knocks people off the Cycle of Growth. It also knocks them onto a Cycle of Impoverishment. This is because low savings can lead to capital consumption. “Consuming” capital doesn’t mean “eating the net.” It means that the net eventually wears out with use, and to maintain it requires diverting possibly consumed resources away from consumption and toward repair/replacement. Without sufficient savings, capital goods enter a state of disrepair. The net eventually tears and fish start swimming through it, at which point the fisherman must resort again to low-productivity hand-fishing, and finds himself back on the brink. Another islander waves a club at Able, and suggests, “How about this?” threatening to plunder Able’s savings. Such brigandage has also kept entire peoples poor throughout history and pre-history. Constant raids by roaming hordes will also discourage savings and break the Cycle of Growth. Sometimes the raiders settle in, and, through propaganda, transform themselves into a “state,” and their plunder into “taxation.” What is particularly devastating to the Cycle of Growth is the kind of state plunder called, “proscription.” In ancient times, when an individual managed to accumulate enough wealth, he often became a tempting one-stop shop for loot, and so the state would find some excuse to imprison or execute him so as to facilitate his total expropriation. This explains the rage for “buried treasure” in times and places where princes were particularly grasping. Of course, modern democracies plunder too, often under the cover of egalitarianism and through “progressive taxation”. The more you save, the more you’re taxed. This too is particularly inimical to the Cycle of Growth. Then a little bird asks if Able’s penchant for accumulation is “greedy” and bad. “Bad for whom?” responds a wise owl. There are only so many fish Able can eat, and only so many uses for his nets. To maximally benefit from his tremendous productivity, he must offer his products to others in the community in exchange for goods and services. And through exchanges like investments, loans, and wages, non-savers can get access to capital goods that would have otherwise been out of reach. For example, Able rents out his nets and loans out his fish at interest. This enables higher-time-preference islanders like Baker and Charlie to increase their productivity and living standards. And since all exchanges are, by definition, projected by both willing parties to be beneficial, the more exchanges the saver makes, the more he benefits the public. Savings and capital benefit everyone, not just the saver and capital accumulator. The Cycle of Growth lifts the entire community. And so when egalitarianism and plunder discourage saving, it keeps the entire community down, hurting not only the savers, but everyone who might have exchanged with the savers. There is nothing “fishy” about savings, capital accumulation, productivity, and peacefully acquired wealth. But to paraphrase an old saying, fish and plundering visitors start stinking very quickly. As Ludwig von Mises wrote: “Every single performance in this ceaseless pursuit of wealth production is based upon the saving and the preparatory work of earlier generations. We are the lucky heirs of our fathers and forefathers whose saving has accumulated the capital goods with the aid of which we are working today. We favorite children of the age of electricity still derive advantage from the original saving of the primitive fishermen who, in producing the first nets and canoes, devoted a part of their working time to provision for a remoter future. If the sons of these legendary fishermen had worn out these intermediary products–nets and canoes–without replacing them by new ones, they would have consumed capital and the process of saving and capital accumulation would have had to start afresh. We are better off than earlier generations because we are equipped with the capital goods they have accumulated for us.” This essay is adapted from the author’s lecture, “Nothing Fishy About Growth” delivered on November 8, 2013 at the Mises Institute’s “How Does an Economy Grow? A Seminar for High School and College Students.” Video embedded below and slides available here. Entire comic book How an Economy Grows and Why It Doesn’t by Irwin Schiff available in PDF and HTML.

How Saving Grows the Economy

A Comic Book Lesson in Capital Accumulation

October 6, 2014

Political Theatre

- For DOGE to Hunt Waste, It Needs Ron Paul to Sic Itt

- Defend Rudy!

- Bishop Strickland: God will punish bishops for their silence while Pope Francis destroys the Church

- Bill Gates wants to fight ‘climate change’ by vaccinating cows to stop them from emitting methane

- Christmas present

- Why Muslim Trump supporters are pushing president-elect to name Ric Grenell Secretary of State

- Michael Flynn: Remove Biden Now!

- How Tulsi Gabbard created a ‘media meltdown’ after Trump cabinet pick: Rob Finnerty

- Russia Responds

- MORE

LRC Blog

- “Argentina Stands With Israel”

- British Storm Shadows? Russian ICBMs? How Far Will Escalation Take Us?

- Even Elon Musk Cannot Make Government Bureaucracy “Efficient”

- Trump’s Immigration Plans: The Good and the Bad

- The US Just Escalated its Proxy War with Russia. Rothbard Explains Why that’s a Problem.

- Definitive Proof that Trump Made the Right Choices with Tulsi and Gaetz

- Can An Economic Catastrophe Be Prevented?

- America’s Untold Stories: The Plot to Kill President Kennedy in Chicago with Vince Palamara

- WWIII? NATO Missiles Strike Deep Inside Russia!

- BREAKING: Watch Trump Read His Deep State Enemies List And See Every Official Start Sweating

- MORE