Wagner's Ring on the Lust for Power

September 2, 2013

I can’t listen to that much Wagner. I start getting the urge to conquer Poland. Woody Allen

The opera world is celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of Richard Wagner (born May 22, 1813) with 15 productions of his four-opera music drama Des Ring der Nibelungen (Ring of the Nibelung) in 2013—10 in Europe, 2 in the UK, 2 in the U.S., and 1 in Australia. Putting on this many productions of The Ring in one year testifies to the growing appreciation of the artistic genius of its composer.

The Ring was first done in 1876 in Bayreuth. Since then 212 Ring cycles have been performed there. The first Ring in the U.S. was performed in 1889 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The Met has now done 113 complete Ring cycles in its 130-ye

ar history. Third in the world is Seattle Opera, with 41 Ring cycles in its 50-year history under two general directors, Glynn Ross (18, beginning in 1975) and, for the last 30 years, Speight Jenkins. He has put on 23 cycles, performed first in a postmodern production and now a naturalistic “green” Ring. (People from all 50 states and 22 countries attended the three Seattle Opera cycles this year.)

Wagner’s Ring is a story about gods, dwarfs, and giants; a dragon; and several humans, including a young Siegfried, billed as the hero of the piece. It has murders and incest and magic, where a dwarf turns himself into a giant snake and then into a tiny toad. One need not know anything about The Ring to become absorbed in the story and moved by it when attending a good production that has captions of the libretto displayed above the stage (supertitles). As Stephen Wadsworth, director of the Seattle Opera Ring points out, “It’s a fantastic story, a story that resembles a complex modern novel more than a dusty old Norse epic.”

The Ring’s tale comes from Norse mythology, in large part from 13th century Icelandic texts (Poetic and Prose Eddas and Völsunga Saga). Myths reveal the basic truths about human nature. They are a symbolic distillation of human experience, and The Ring is especially important to us today for what it tells us about the pursuit of power.

The two principal components of power in The Ring are an all-powerful ring made of gold and a magical metallic veil the ring’s possessor is empowered to make called the tarnhelm. The tarnhelm can render its wearer invisible and able to watch unobserved everything that is happening. The tarnhelm in myth presages what we now must confront living in the U.S. Surveillance State with its all-seeing National Security Agency (NSA). Apropos the allegorical tarnhelm, power brokers like to call the NSA “No Such Agency.”

The four operas that make up the Ring, which Wagner calls music dramas, are Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold), Die Walküre (The Valkyries), Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods). They are performed on successive nights, usually over a six-day period.[amazon asin=B008ER9QLK&template=*lrc ad (right)]

(Without breaks The Ring is 14 to 17 hours long, depending on the conductor—Karl Böhm conducts the four operas in 13 hours, 42 minutes [1967, Bayreuth]; Daniel Barenboim, 14 hr 42 min [2013, BBC Proms concert performance]; Wilhelm Furtwängler, 15 hr 02 min [1953, live studio recording for RAI]; James Levine, 15 hr 41 min [1989-90, Met]; and Reginald Goodall, 16 hr 52 min [1973-1977, English National Opera]. The score is written for 120 instruments, including 6 harps, some of them newly invented, like the Wagner tuba and contrabass trombone, and for 33 solo voices, including a large chorus of vassals and handmaidens in one of the acts. It has 800 pages of dialogue and stage instructions.)

Das Rheingold focuses on acquiring power. It starts with Alberich, a dwarf, flirting with mermaids (Rhinemaidens) in the Rhine River (in the river). He spots gold and learns that one can make an all-powerful ring from it by forswearing love. Unable to score with the mermaids, Alberich takes the gold, renounces love, and forges the ring. Relishing the power it gives him, Alberich enslaves his fellow dwarfs, the Nibelungs and forces them to keep digging for more gold—until Wotan (with help) tricks Alberich and seizes the ring. Wotan, the supreme god, uses the ring to pay for his new palace (Valhalla), giving it reluctantly to the two construction workers who built it, the giants Fasolt and Fafner. Alberich places a curse on the ring, swearing death to all who possess it. Right away, as per the curse, Fafner kills his brother Fasolt, keeping the ring (and the tarnhelm and the gold) for himself.

(in the river). He spots gold and learns that one can make an all-powerful ring from it by forswearing love. Unable to score with the mermaids, Alberich takes the gold, renounces love, and forges the ring. Relishing the power it gives him, Alberich enslaves his fellow dwarfs, the Nibelungs and forces them to keep digging for more gold—until Wotan (with help) tricks Alberich and seizes the ring. Wotan, the supreme god, uses the ring to pay for his new palace (Valhalla), giving it reluctantly to the two construction workers who built it, the giants Fasolt and Fafner. Alberich places a curse on the ring, swearing death to all who possess it. Right away, as per the curse, Fafner kills his brother Fasolt, keeping the ring (and the tarnhelm and the gold) for himself.

Die Walküre is about incestual love and a sword. With the tarnhelm Fafner has turned himself into a dragon, to better protect him and the gold. Forming a plan to recoup the ring, Wotan leaves a sword named Nothung embedded in a tree for his human son Siegmund. Since he is an independent person and not bound by any agreement with the giants, Wotan figures Siegmund can legitimately kill Fafner and get the ring back for him. But Wotan’s wife Fricka convinces him that he must squash this plan and let Siegmund be killed as punishment for sleeping with his sister, Sieglinde. Wotan gives instructions to his warrior goddess daughter Brünnhilde not to protect Siegmund, but she comes to his defense, to no avail. Wotan shatters Siegmund’s sword, and Sieglinde’s husband kills him. When Wotan is not looking Brünnhilde whisks Sieglinde away to safety knowing that she carries Siegmund’s child. Punishing her, Wotan strips away Brünnhilde’s immortality and places her in a lasting sleep on a high mountain rock ringed by fire—to be awakened only by the bravest of men.[amazon asin=B000YD7S12&template=*lrc ad (right)]

Siegfried, in the opera Siegfried, is the one who does that. He also accomplishes what his father Siegmund had failed to do and kills Fafner the dragon. Left an orphan when his mother dies in childbirth, Mime, Alberich’s brother, rears Siegfried in the forest without any human contact. Mime sees Siegfried as the means to acquire the ring and its power for himself. Goaded by Mime to learn fear, Siegfried reforges the sword (Nothung) required to kill Fafner. Deed done, he happens to taste the dragon’s blood on his finger, which allows him to understand the language of songbirds. Clueless about the ring, the bird tells Siegfried to retrieve it and the tarnhelm. The bird (sung by a coloratura soprano—The Ring’s only one) then directs him to the rock where Brünnhilde sleeps. Still fearless, Siegfried braves the encircling fire, finds Brünnhilde, and removes her Valkyrie’s shield, discovering to his surprise that she is a woman, the first one he has ever seen. Now feeling fear, he awakens her; and Brünnhilde becomes his bride. (The saying “The opera isn’t over until the fat lady sings” comes from Siegfried, where Brünnhilde awakens and starts singing with 29 minutes left to go in this 5-hour opera, including intermissions—except that most Brünnhildes today are, fortunately, trimmer.)[amazon asin=B000056JST&template=*lrc ad (right)]

Götterdämmerung begins with Siegfried giving the ring to Brünnhilde before he sets out on new adventures. Traveling down the Rhine he meets the Gibichung family: Gunther, head of the clan; Gutrune, his sister; and Hagen, their half-brother, who happens to be Alberich’s son. Gunther and Hagen slyly place Siegfried under the spell of a drug-induced memory loss. Forgetting Brünnhilde, he falls for Gutrune and becomes betrothed to her. He goes back to Brünnhilde on the rock wearing the tarnhelm disguised as Gunther, forcibly takes the ring, and claims her for his new “blood brother” Gunther. Siegfried’s unwitting betrayal of Brünnhilde leads to his death. Hagen, knowing the ring’s power and told by Brünnhilde how to do it, fatally stabs an unsuspecting Siegfried in the back, the only vulnerable part of his body. After a stirring funeral march Siegfried’s dead arm rises up ominously when Hagen attempts to take the ring. He shrinks back and Brünnhilde steps in and removes the ring. Then, with Alberich watching, she hands the ring over to the Rhinemaidens as Siegfried’s body and the world burn, ending the reign of the gods.[amazon asin=B00006L9ZW&template=*lrc ad (right)]

Richard Wagner was born in a Germany that was then a confederation of sovereign states, in an age when Fredrick the Great, King of Prussia would say, “I speak French to my courtiers, Latin to my confessor, and German to my horse.” At age 26, Wagner went to Paris, the operatic capital of the world, to make his name. He failed and 2½ years later returned to Germany bitter. He started writing the libretto for Des Ring der Nibelungen back in Dresden in 1848, shortly before he was forced to flee to avoid arrest and possible execution for participating in the Dresden uprising of 1849. Wagner finished the libretto living in exile in Zurich and worked on the music for The Ring over a 20-year period, also composing Tristan and Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg during that time. He completed The Ring in 1874.

(Like many of his contemporaries Wagner was an anti-Semite. But he was a notorious one, publishing a 20-page article, later republished as a pamphlet, Judaism in Music, where he attacked the Jewish composers Mendelssohn, by name, and Meyerbeer, unnamed, who he identified as the world’s leading opera composer living in Paris. He branded Jews in general as “repellent.” Wagner nevertheless had Jewish friends and had the son of a rabbi, Hermann Levi, conduct the world premiere of his dearest work Parsifal. As[amazon asin=B00006L9ZY&template=*lrc ad (right)] a result, writes his biographer Martin Gregor-Dellin, “[Wagner] alienated friendly critics, forfeited the trust of his friends, and incurred the implacable resentment of posterity.” Nevertheless, a true work of art stands separate from the artist who created it, on its own. As D. H. Lawrence puts it, “Never trust the artist. Trust the tale. The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.”)

One of the most striking cases of the pursuit of power in human history is Adolf Hitler (1889-1945). Hitler loved Wagner’s operas and considered him to be the cultural hero of the fascist Third Reich. The first opera he saw at age 12 was Lohengrin; and Frederic Spotts, in his Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics, figures that Hitler attended close to 100 performances of Die Meistersinger. But he didn’t particularly like Götterdämmerung, with how it ends, and Parsifal. (The last musical event Hitler attended, in 1940, was a performance of Götterdämmerung, and after Stalingrad all he wanted to hear were the light operas of Franz Lehär. He told Goebbles that after the war he would see to it either that religion was banished from Parsifal or that Parsifal was banished from the stage.)

David Bowie calls Hitler “the first modern rock star.” Like Fafner turning himself into a dragon, at staged events Hitler (with practice)[amazon asin=1590201787&template=*lrc ad (right)] would don a demonic persona, employing as Frederic Spotts describes it, a “hypnotic sort of theatrical fanaticism.” He would captivate people, leaving them spellbound. And like Alberich controlling his Nibelung horde, his carefully choreographed mass rallies, as Spotts puts it, “were a microcosm of Hitler’s ideal world: a people reduced to unthinking automatons subject to the control not of the state, not even the party but to him personally and that unto death.” Not heeding the mythic message of The Ring, like Wotan brooding in Valhalla as the world burns Hitler hid in his bunker as his 1,000-year Reich collapsed in flames around him. (One room of the bunker, explored after his suicide, was found to be filled with illustrated books on opera house architecture.)

Wagner started out as a socialist and in his thirties in Dresden was a left-wing revolutionist. From this perspective The Ring has been interpreted as a political allegory critiquing capitalism, George Bernard Shaw espoused this view (in 1898) in The Perfect Wagnerite: A Commentary on the Niblung’s Ring—where Wotan and the gods are the aristocracy; Alberich, a capitalist; the Nibelungs, under Alberich’s thumb, the proletariat; the giants are peasants; and Siegfried is a model for the free socialist “New Man.”

For the 2013 Bayreuth Ring celebrating Wagner’s bicentennial, directed by Frank Castorf, the set for Siegfried sports Mount  Rushmore-like sculpted heads of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao, with scaffolds around them. Its designer, Aleksandar Denic, explains: “These men changed the world. Each person can decide whether it was for better or for worse. The scaffolds could mean that the heads are being destroyed or repaired. Most of all, they show that someone is still working on the project.” One may be sure that a carved head of Hitler will never be displayed on the Bayreuth stage. Instead, this production features two communist pursuers of power, Stalin and Mao, who each killed and starved to death millions more people than even Hitler did.

Rushmore-like sculpted heads of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao, with scaffolds around them. Its designer, Aleksandar Denic, explains: “These men changed the world. Each person can decide whether it was for better or for worse. The scaffolds could mean that the heads are being destroyed or repaired. Most of all, they show that someone is still working on the project.” One may be sure that a carved head of Hitler will never be displayed on the Bayreuth stage. Instead, this production features two communist pursuers of power, Stalin and Mao, who each killed and starved to death millions more people than even Hitler did.

The Ring is not a fascist, or a socialist, or a communist work—understanding that fascism, socialism, and communism are three strains of the same species of collectivist political animal. These breeds are motivated foremost by their desire for power, acquired by whatever means necessary. For such people the end—to obtain measureless power to control others and rule one’s country and ultimately the world—justifies the means employed—murder, enslavement, gulags, and forced psychiatric hospitalization of dissidents. The Ring warns against seeking power. It teaches instead that the pursuit of power is incompatible with a life of true feeling, that wielding power destroys the capacity for love and poisons people who seek it.

Wotan comes to realize that the price of pursuing and maintaining power is too high. This message is as important today in the 21st century as ever. Political power corrupts both a person’s morals and judgment. As James Madison observed, “It will not be denied that power is of an encroaching nature.” And Eric Hoffer (in 1954) writes, “Our sense of power is more vivid when we break a man’s spirit than when we win his heart.”

Wagner was 41 years old when a friend suggested that he read a book by the (German) philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860). The book was The World as Will and Representation. Wagner read it, over and over, initially four times, and it changed his life.[amazon asin=B00700YVIU&template=*lrc ad (right)]

Wagner’s discovery of Schopenhauer inspired him to compose the operas Tristan and Isolde and Parsifal, which address the philosopher’s intuitive insight into the innermost nature of things—Tristan on human sexuality and Parsifal on compassion. Schopenhauer was the first philosopher to posit a philosophical significance to sex and the orgasmic sense of oneness sexual partners can experience. He accorded a similar significance to the sense of oneness that can engulf a person feeling compassion. He injected Hindu and Buddhist beliefs into Western philosophy, the first philosopher to do this. And as Schopenhauer sees it, music reigns supreme. It speaks to the inner nature of things. Along with sex, compassion, and mystical experiences, music especially enables us to sense intuitively the striving, pulsating, undifferentiated nature of the rock-bottom reality of things as they are in themselves, a reality that lies outside the content of experience and is inaccessible to human knowledge. (Following Kant, Schopenhauer termed the world that we perceive and measure the vorstellung and the real world of things as they are in themselves that underlies the perceived world, the Ville, or Will in English, which Kant termed the Noumenon.)

Schopenhauer freed Wagner from his stated adherence to the equality of text and music, as espoused in his 1850-51 treatise Opera and Drama. Leaving the libretto for The Ring unchanged (except for the ending, which he kept revising), Wagner instead focused on the music, freeing it from a one-to-one correspondence with the text. What started out as a political allegory became what he intended it to be, a total work of art—a Gesamtkunstwerk. In his autobiography Mein Leben (My Life), Wagner says this about Schopenhauer: “He has come to me in my solitude like a gift from heaven.”

Socialists don’t like Schopenhauer. He had a low opinion of G.W.F. Hegel, the godfather of socialism, and dialectical change—a process of historical evolution where the group has primacy over the individual and the state over the group. Following Hegel, Karl Marx formulated his concept of dialectical materialism with its labor theory of value. The state is the highest order of humanity, closest to the “Absolute Spirit/Idea” in the dialectical process; and individuals owe their obedience and subservience to it. But as history has shown, this is a recipe for political absolutism and ultimate power. Schopenhauer takes this view of the matter: “It is easy to see the ignorance and triviality of those philosophers who, in pompous phrases, represent the state as the supreme goal and greatest achievement of mankind, thereby achieving the apotheosis of philistinism.”

Schopenhauer is the antidote to Hegel and his collectivist offspring. (See my article “The Philosophical Basis of the Conflict between Liberty and Statism,” available online HERE.)

Wagner read Schopenhauer’s last published work, Parerga and Paralipomena (Greek for “Appendices and Omissions”), a collection of[amazon asin=0199242208&template=*lrc ad (right)] philosophical reflections that contain his essay “Wisdom of Life” (available online HERE). Steeped in this philosopher’s writings, Wagner’s political views changed. As the philosopher and Wagner scholar Bryan Magee sees it: “His significant movement was not from left to right but from politics to metaphysics.” If anything, Wagner became, an anti-state anarchist—a philosophic one, not the bomb-throwing kind. (Some critics, like Wagner specialist Barry Millington, downplay Schopenhauer’s influence on Wagner, marginalizing him as a pessimist and a misogynist. A better appraisal of Schopenhauer, however, would be to portray him as a realist, rather than a pessimist, as his “Wisdom of Life” attests.)

Wagner’s Ring lends itself to a classical liberal interpretation better than a socialist one. Wotan encroaches on Alberich and steals his property, the ring and tarnhelm—and the gold from the Rhine that the nymphs had been guarding. But Wotan does honor his agreement with Fasolt and Fafner and gives them the ring (and tarnhelm and gold hoard) in payment for their building his palace. As Richard Maybury so clearly explains, two fundamental laws govern human affairs, which makes civilization possible: 1) Do all you have agreed to do; and 2) Do not encroach on other persons or their property. There are three basic political conditions: liberty, tyranny, and chaos. All political systems are a variation or combination of these three states. Citizens in a society that follows these laws possess liberty; and with liberty come privacy, private property, free markets, entrepreneurs, and general prosperity. Tyranny and/or chaos occur in societies that flout these two rules. They end up like the mythical one in The Ring. (See Maybury’s 9-minute talk “Why Does Power Corrupt?” on YouTube, his book Whatever Happened to Justice? and website www.chaostan.com.)

The first law, Do all you have agreed to do is carved (in so many words) in runes on Wotan’s spear. He regrets having to obey that law and hand over the all-powerful ring to the giants. Wotan wants it back. Nevertheless, he finally decides to renounce the will to power and let Alberich have his ring (after all he was the one that made it).

Some individuals, like Wotan, Alberich, Mime, and Hagen in The Ring, are driven to gain the power to control others and rule their lives. Most such people, we now know, are sociopaths. Siegfried and Brünnhilde do not covet the ring, except as a token of their love, and eschew its power. In examining the choices and decisions people make, Schopenhauer found that human behavior is directed by three principal motives: self-interest, the most common one; compassion; and malice. Self-interest drives all living things. Malice appears to be confined to our conscious species and fortunately is not common. Compassion has two cardinal virtues: loving kindness and natural justice. And from a philosophical and moral standpoint, compassion is the key motive. Brünnhilde is the true hero of the work with the forgiveness and compassion she shows for Siegfried and the world’s state of things.

On a metaphysical level The Ring tells us that the unloving and corrupting pursuit of power is antithetical to the innermost essence of things. Wagner embraces a Schopenhauerian and Buddhist view of the matter, where the ultimate reality is that there are no separate souls, for in the end we are all one. In The Ring the power-driven world of gods, giants, and dwarfs comes to a fiery finish, ignited by Siegfried’s funeral pyre. Brünnhilde impounds the ring that gives its bearer measureless power to rule the world and places it in safe-keeping with the nymphs of the Rhine, out of reach from the grasp of individuals who seek such power. As people stand by watching and watch the corrupt one burn, the world is reborn. The Ring ends musically, without words, in a major key (D-flat major) expressing Brünnhilde’s compassion and suggesting that perhaps the next time it will be better.

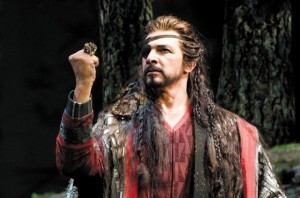

Photos above:

1—In the Seattle Ring, Wotan pondering the prize he has just seized.

2—In the first scene of Seattlle’s Rheingold, Alberich, while unsuccessfully cavorting with Rhinemaidens in the river, notices the gold.

3—The 2013 Bayreuth Ring sporting the Mount Rushmore-like carved heads of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao.

Ring-Related Recommendations:

Videos:

The 1991-92 Kupfer/Barenboim Bayreuth Der Ring Des Nibelungen. A 4-disc Blue-ray version of this (complete) Ring is now available[amazon asin=B008VNIA32&template=*lrc ad (right)] for $57.44! (An 11-disc DVD version of it is also available for $58.25.) Of the three classic Ring videos, the 1979-80 “sociopolitical” Chéreau/Boulez Bayreuth Ring ($120 on Amazon, DVD only), the 1989-90 “traditional” Schenk/Levine Met Ring ($80, DVD only), and the Kupfer/Barenboim Ring, Kupfer’s “psychological” Ring with Daniel Barenboim conducting is the best of the three—and the cheapest. Barenboim is a fine conductor (and Furtwängler disciple). He is arguably the best modern-day conductor for this work.

Triumph of the Will by Leni Riefenstahl. This film on Hitler’s 1934 rally at Nuremberg is the ultimate visual depiction of power, in a remastered, high-resolution edition.

CDs:

Magic Fire, Broken Vows, and Passionate Love: Speight Jenkins’ Guide to Wagner’s Ring. An engaging introduction to this work by the General Director of Seattle Opera, with musical excerpts from the 1952 Keilberth Bayreuth Ring. A 4-CD set. This is a great way to start with The Ring.

Furtwängler’s 1950 La Scala Ring Cycle – Box Set – by Pristine Classical. Andrew Rose’s XR remastering of the cycle for Pristine Audio, in 2013 (€162.00 – $215.90). Many Wagnerians, myself included, say that this is the best Ring Cycle ever recorded, despite its less-than-perfect sound. Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954) gets into the fabric of this work in deeper and more revelatory way than any other conductor. And Kirsten Flagstad as Brünnhilde is a force of nature. Surprisingly, the Fonit Cetra LP recording of this cycle is more muddy and indistinct and (a striking admission for an analogue person like me) pales in comparison to this Pristine Classical CD set of the cycle. This is the only 1950 Furtwängler La Scala Ring to get, on the www.pristineclassical.com website (it is not available on Amazon).

One hopes that at some point BBC will release CDs and/or a FLAC download of Barenboim’s widely heralded concert performance of the Wagner Ring at the 2013 BBC Proms Classical Music Festival. (It might be possible to obtain now a RAR-file download of the broadcast of this Ring as a member of the Google group SymphonyShare.)

Books:

Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century by Martin Gregor-Dellin. The best one-volume biography of Wagner published on the hundredth anniversary of his death (1983).[amazon asin=0151771510&template=*lrc ad (right)]

Wagner: His Life and Music by Stephen Johnson (2007, 256 pages with 2 CDs). This former Chief Music Critic for The Scotsman and commentator for BBC Radio 3 has written an engaging, concise biography of Wagner with musical examples on 2 CDs that come with the book. Highly recommended.

Wagner’s Ring: Turning the Sky Round by M. Owen Lee (1989, 120 pages). Five relatively short essays on The Ring presented by Father Owen Lee at intermissions of performances of the cycle. You will find yourself captivated by this beautifully phrased and insightful account of The Ring operas.

English National Opera Guides on the Wagner Ring: ENO Guide 35—Das Rheingold/The Rhinegold; Guide 21—The Valkyrie (Die Walküre); 28—Siegfried; and ENO Guide 31—Twilight of the Gods (Die Götterdämmerung). Each Guide contains the text of the opera translated by Andrew Porter, musical notations of the key musical motifs—also known as leitmotifs (short melodic phrases associated with specific characters, emotions, situations, and elements)—in the work, and interesting articles on the various operas. These guides are useful to have when listening to CDs of The Ring.[amazon asin=0714544361&template=*lrc ad (right)]

The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy by Bryan Magee and published in the UK as Wagner and Philosophy (2001, 416 pages). A “lucid, clear summary of Wagner’s philosophical views,” as one customer reviewer on Amazon.com aptly puts it. A great read.

Heart in Hand — My book on the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (and his influence on Wagner), the films of Woody Allen, and on my life as a heart surgeon. See especially Chapter 5, “The Metaphysics of Music,” available online HERE (28 pages); Chapter 3, “The Philosophical, Moral, and Medical Importance of Compassion,” HERE (24 pages); and Chapter 2, “The Significance of Sex,” available HERE (25 pages). Living in Seattle for the last 40 years and attending many of the Seattle Opera Ring cycles fueled my interest in Wagner and Schopenhauer.

Benjamin’s Ring: The Story of Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung for Young Readers by Roz Goldfarb (104 pages with[amazon asin=1466497246&template=*lrc ad (right)] illustrations, $11.65 on Amazon). I bought this book for my 10-year-old grandson and found it to be a fun read for old readers (like me) as well. It begins: “Once upon a time and a long time ago, high up in the clouds lived a family of gods. At that time the world was divided into three separate parts: the gods, who lived above; the mortals who lived on the earth; and those who lived under the ground were called the Nibelung.”

Websites:

www.wagneropera.net A nice site on Richard Wagner and his operas, with information on the Bayreuth Festival, Wagner performers, and among other things, recommendations on Wagner DVDs and CDs and books about him and his operas.

www.wagnerheim.com A more than 1000-page, scene-by-scene analysis of Wagner’s Ring, where 178 musical motifs are identified by musical notation and audibly (with MP3 files) and pinpointed where they appear throughout the libretto—the fruit of a life-time’s study of The Ring by Wagnerian Paul Heise.

The Best of Donald W. Miller, Jr., MD