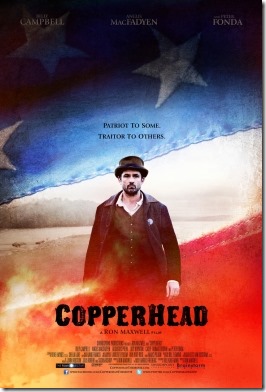

Finding a movie about war with no actual battle scenes is pretty rare. A rarer find is a war movie that depicts the effects of war upon communities at home. Even rarer is a war movie that makes this point about the American Civil War. Copperhead, I am pleased to say, is that movie, and it is a long overdue story that must be told. I had the opportunity to view a pre-release of the film courtesy of Swordspoint Productions and director Ron Maxwell, who also directed Gettysburg and Gods and Generals.

Copperhead is a historical drama, but is in many respects a parable that speaks to the modern world. The movie takes place in upper New York within a community called “The Corners.” The year is 1862, and the War Between the States is in full swing. It primarily revolves around two families: the Hagadorns and the Beeches. Both families are integral parts of the Corners community, and both are very much against slavery. Jehoiada Hagadorn, however, supports the Civil War, whereas Abner Beech opposes it on moral and Constitutional grounds.

The Corners is a tight-knit community, shown through the various aspects of community life. The people clearly care for each other. However, the community is becoming divided between the majority who support the war and the minority who do not. Those who dissented from the Civil War were called “Copperheads,” and Abner Beech is the most outspoken Copperhead in the Corners.

But why not support this war? Should it not be fought to “preserve the union” or to free slaves? Abner Beech says these reasons do not justify mass killing. He is not a slaver, not an expansionist – he simply does not want to support death. Abner says to one of his war-supporting friends, “You mean more to me than any Union” despite disagreeing with him. Abner abhors slavery, but he abhors war as a solution.

Though it is clear in the film that the North and the South have come into conflict over slavery, to Abner war is “a cure worse than the disease” and he believes that promoting peace is the only way to truly resolve conflicts. Unfortunately, even the local church fails to live up to such a standard. During a sermon when the minister is preaching about the war, Abner leaves the service in protest. As he departs, he asks the congregation, “Blessed are the peacemakers – is that still in the Bible?” The only answer is Hagadorn slamming the door behind the Beech family.

Abner recognizes how politics is destructive to the community. In his words, “This community is broken.” Indeed, his statement is representative of the entirety of the United States at the time. Those who have no substantial reason to be at odds with friends and brothers now are, because they are supporting a war where friends and brothers kill other friends and brothers in the name of preserving a “brotherhood” of “states.” The irony should not be lost upon the viewer.

The conflict between the film’s fathers (Abner and Hagadorn) with their respective sons further emphasizes how war is destructive to families. This unusual “dichotomy of sons” shows how deeply this community’s wounds go with respect to war. Abner’s son Jeff does not fully embrace his father’s anti-war views. His love for Hagadorn’s daughter, noble as that love might be, causes him to seek acceptance from her and her father by supporting the war and even joining the army to fight for the union.

While Jeff supports the war, Hagadorn’s son Benaiah – also Jeff’s best friend – is not nearly so positive. Benaiah may not be an outright Copperhead, but he is clearly skeptical about the usefulness of war. When Jeff, however, is listed among the missing after the Battle of Antietam, Benaiah is driven to go south and find Jeff despite the danger. Benaiah says that Jeff “would have done the same for me,” alluding to that Golden Rule that the Corners seems to have forgotten: “Treat others the way you would want to be treated.”

Besides opposing the Civil War in principle, Abner understands what war does to participants and to their communities. Politics has evolved much since 1862, but violence has not and Abner’s words speak to all Americans, and especially Christians, today: “War is a fever… you do things out of your right mind you wouldn’t do if you weren’t sick… You lose sight of who you really are.”

Besides opposing the Civil War in principle, Abner understands what war does to participants and to their communities. Politics has evolved much since 1862, but violence has not and Abner’s words speak to all Americans, and especially Christians, today: “War is a fever… you do things out of your right mind you wouldn’t do if you weren’t sick… You lose sight of who you really are.”

Finally, for the Christian this film has an additional message about the Christian faith, a special word that clearly has Ron Maxwell’s Christian worldview written all over it. Both Hagadorn and Abner are deeply religious, but they practice their faith in two very different ways. Hagadorn is like a firebrand preacher who always talks a good game, always quoting Scripture and displaying great “spiritual” knowledge. Yet he is the main source of conflict in the Corners, and he even repeatedly demeans his children using Scripture like a bludgeon. Abner, in contrast, does not need to flaunt Scripture to show how “Christian” he is. Instead, he stands by his principles and has built his faith upon a steady foundation. Incidentally, a symbol of his “foundation” is still standing at the end of the film – but I will let you watch the movie to see what I mean. The question for the viewer is simple, what kind of Christian are you going to be?

In conclusion, there is nothing in film history like Copperhead, in which war is seen to chip away at the foundation of a community and drive wedges of enmity between those who should have been at peace. It is a great lesson about what the fever of war can do to anyone. For Christians, especially Christian libertarians, it is a moving parable about how faith should affect ones ethics in the political arena. I highly recommend this film and encourage every reader to “demand the movie” at their local independent theater.

Norman invites you to comment on this article at LibertarianChristians.com