I was born in Detroit in 1954. It was the year Detroit’s population peaked at just under 2 million and made Detroit the nation’s 4th largest city. Most Detroiters were white, gainfully employed and educated. The automobile industry was experiencing full employment and wages and benefits were among the best in the nation. Automotive success supported a myriad of other businesses from construction to retail to recreation. There was comparatively little crime. My father who survived 30 missions as a navigator on a B-24 bomber was free of Korean military service, and was busy building his practice as a certified public accountant. We had clean clothes and my mother put three square meals on the table daily. We ate real butter, whole milk, fatty beef and lots of sugar. We played in the streets all day, ventured miles from our home without a cell phone or parental oversight, and rode bikes without helmets. The Twin Pines truck would arrive in our driveway and place a delivery of cold glass milk bottles with cardboard caps into our milk chute. I laughed at Soupy Sales, Milky The Clown and the Three Stooges on one of the four channels our TV featured. Changing it required getting off the couch and turning a knob. On occasion you had to turn the rabbit ears to eliminate "snow." We never had our Halloween candy x-rayed. My parents drove exquisitely large chariots of two-toned steel with huge tail fins and no seatbelts. Life was good in my Detroit.

Black Detroiters — then referred to as Negroes, coloreds or worse — no doubt have less idyllic memories of those days in Detroit. Detroit in the 50’s was a firmly segregated city. Like the TV’s of the time Detroit was black and white. We rarely saw "negroes," except for those who took the bus to come clean neighborhood homes or work in car washes. My only direct contact was with our handyman, Jimmy Wilson. As a young boy I had no idea how or where Jimmy lived. I only knew him as a soft-spoken older guy who did great work, told great stories over a cool drink with us and always had a smile. If there was trouble brewing between the races I never knew it from Jimmy.

In the 60’s Detroit felt the same wave of change that was sweeping the nation. Still, life in my Detroit was everything a young boy could ask for even while sharing a bedroom with my two brothers. One day, I met two boys about my age while out riding bikes with my friend. They were not from my neighborhood. I knew because they were not my color. They asked if they could use our bikes to race each other. They took off swiftly and were never seen again — neither were our bikes. My father was furious with me for trusting two colored boys with my new bike. A white police officer who came to our home to take a stolen property report warned my parents, "They’ll take anything that isn’t nailed down." It was my first lesson about the Detroit I did not live in and the end of my Leave-It-To-Beaver world.

In the 60’s Detroit felt the same wave of change that was sweeping the nation. Still, life in my Detroit was everything a young boy could ask for even while sharing a bedroom with my two brothers. One day, I met two boys about my age while out riding bikes with my friend. They were not from my neighborhood. I knew because they were not my color. They asked if they could use our bikes to race each other. They took off swiftly and were never seen again — neither were our bikes. My father was furious with me for trusting two colored boys with my new bike. A white police officer who came to our home to take a stolen property report warned my parents, "They’ll take anything that isn’t nailed down." It was my first lesson about the Detroit I did not live in and the end of my Leave-It-To-Beaver world.

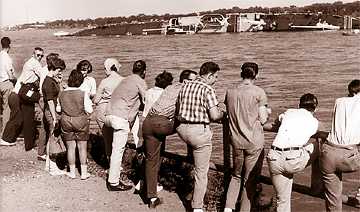

We always went into downtown Detroit for special occasions like birthday dinners, premier movies, and the Detroit Tigers or Lions games at Tiger Stadium. There were local traditions like the Thanksgiving Day parade and breakfast with Santa at J.L. Hudson’s department store. On trips downtown we would encounter "coloreds" working as vendors at the ballgames, elevator operators at JL Hudsons or cleaning up tables at the best restaurants. I never thought twice about the order of things. Downtown was where everyone went if they were lucky. It was where things were happening and where the streets were full of people busy enjoying city life. City busses travelled electrically, with huge antennae that were connected to a system of overhead wires. The Ambassador Bridge and the Windsor tunnel connected Detroit to Canada just across the Detroit River. In 1962, my father took us to the foot of the river to join the crowds gawking at the site of the British freighter Montrose which had sunk just beneath the bridge. Good or bad, it seemed that everything worth seeing happened downtown.

The nuns and teachers at my Catholic grade school were in tears and we were all sent home from school early. It was November 22, 1963. Three days later I returned from church to see a replay of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald on TV. Life was about to change.

The nuns and teachers at my Catholic grade school were in tears and we were all sent home from school early. It was November 22, 1963. Three days later I returned from church to see a replay of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald on TV. Life was about to change.

In 1965 my father convinced my mother to consider a larger home in a suburb of Detroit. My father had the house built in 1965 and we moved in on my birthday in 1966. I had my own room, but it felt strange to me. The homes were spread out and everything seemed so far away. We had no milk chute. What was this? I always wanted to return to the city to see old friends and visit familiar environs, but I was consigned to suburban life. My parents wanted to settle into their new neighborhood and I was not old enough to drive.

One year later while we were enjoying a vacation on Mackinac Island between the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan we awoke to news that a riot had broken out in Detroit. On our ride home we passed convoys of military vehicles headed into the city. From the safety of our new suburban home we watched coverage of the riot on TV. Color had come to TV and to Detroit. 43 people died, almost 1,200 were injured and 7,000 were arrested. Property damage, fires and looting were widespread. Tanks and soldiers patrolled the streets with orders to shoot to kill. City busses were converted into makeshift jails. What happened to the city I grew up in so happily? People were stunned, like victims of a natural disaster who had no idea it was coming. Many would say that Detroiters should have seen the handwriting on the wall. In 1943 another race riot took 34 lives in just 36 hours and saw 1,800 arrested. Could the riot be considered the cause of Detroit’s problems or was it simply the ultimate manifestation of them? Regardless of one’s answer the riot of ’67 would transform Detroit forever.

In 1968, the Detroit Tigers won the World Series with black players and white players working together. The entire city celebrated openly and for a moment forgot the horror that it had experienced a year and a half before, but only for a moment.

In 1968, the Detroit Tigers won the World Series with black players and white players working together. The entire city celebrated openly and for a moment forgot the horror that it had experienced a year and a half before, but only for a moment.

White flight, as it was called, continued unabated. Nobody had forgotten the riot of 1967. Block busting was a real estate practice in which Realtors would convince a white homeowner to sell their home to a black family in an otherwise all white neighborhood. When other whites learned that a colored family was moving into their neighborhood they began selling their own homes in panic and at reduced prices. "Coloreds" became Afro-Americans and "black power" became a slogan hopeful to some and feared by others. Downtown had become a ghost town after dark. Store fronts were covered with heavy steel grates and padlocked. You could fire cannons up Woodward Avenue at night and never hit anyone.

The 70’s saw Detroit’s population continue to drop. In addition, those left in the city were less skilled, less educated and less affluent. Those who could leave were leaving taking capital, investments and opportunities with them. Gasoline was 19 cents per gallon and cars were thirstier than ever. The suburbs continued to grow with malls popping up like vegetable gardens. Detroit’s police chief was a white man with a brush cut named John Nichols. Chief Nichols implemented a unit called STRESS, an acronym for stop-robberies-enjoy-safe-streets. African-Americans saw Nichols as the embodiment of racism and STRESS as more of a description of what his police department was causing them. Nationally, this was the era of the so-called black-sploitation films in which white police officers gunned down angry African-American males in city streets. In a case of life imitating art, Detroit police officers engaged in one of the largest manhunts in city history in 1973 following a string of killings of white Detroit police officers by African-American men.

It was also the era of the muscle car. Perhaps more than anything else, the muscle car came to symbolize 70’s Detroit. In a city which was divided racially and struggling economically the muscle car gave the appearance of power in stark contrast to the condition of the city which was churning them out. Yet, the hangover of the 1967 riot lingered and the city seemed mired in a malaise with no real direction forward.

In 1973 Detroit elected it first black mayor. Coleman A. Young was the pride of African-American Detroiters and the scorn of whites living just outside of the city who still considered Detroit part of their birthright. Young defeated Chief Nichols in a clear choice of white establishment versus African American political assertiveness. Brash and outspoken, Young never missed an opportunity to lock horns with white establishment figures. He had a penchant for blaming whites for every problem which had befallen Detroit. It may have been ego or idol worship, but the Detroit Zoo — actually located in suburban Royal Oak — the Detroit City County Building and a city airport would all be renamed after Coleman A. Young. Many blame Young’s twenty year legacy as Mayor of Detroit for the further polarization between black and white Detroiters and the steady decline of the city itself.

After years away from the city, I spent 1973 to 1980 attending college and law school in Detroit. It was my first prolonged exposure to the city in ten years. The University of Detroit Law School has occupied its position on Jefferson Avenue just across from the Detroit riverfront since 1927. I was in the city on a daily basis and spent my leisure time enjoying the restaurants and night life the city had to offer. As young students we were eager to see Detroit in the most positive of lights, but the sad condition of the city was always evident. We were too busy studying for exams and partying to realize that one day some of us would become major contributors to the city’s future. I took a job clerking for a downtown law firm. My situation was typical of many white Detroiters. I studied in the city, I worked in the city and I partied in the city, but I lived outside of the city. It was not just whites who were abandoning the city. Throughout the 80’s, successful black Detroiters also joined the caravan north away from the city limits. The city’s tax base continued to decline and crime was on the rise.

After years away from the city, I spent 1973 to 1980 attending college and law school in Detroit. It was my first prolonged exposure to the city in ten years. The University of Detroit Law School has occupied its position on Jefferson Avenue just across from the Detroit riverfront since 1927. I was in the city on a daily basis and spent my leisure time enjoying the restaurants and night life the city had to offer. As young students we were eager to see Detroit in the most positive of lights, but the sad condition of the city was always evident. We were too busy studying for exams and partying to realize that one day some of us would become major contributors to the city’s future. I took a job clerking for a downtown law firm. My situation was typical of many white Detroiters. I studied in the city, I worked in the city and I partied in the city, but I lived outside of the city. It was not just whites who were abandoning the city. Throughout the 80’s, successful black Detroiters also joined the caravan north away from the city limits. The city’s tax base continued to decline and crime was on the rise.

One could blame those who abandoned the city or one could support their decision. The fact was that faced with the Herculean task of turning the city around or pulling up stakes and moving into communities which were safer, more modern and with greater amenities, most people followed the latter course. Detroit has suburbs which will stand with any community in the country for quality of life. Yet, those who left Detroit were always uneasy about leaving their city behind.

In the 80’s an odd cultism sprang up. Desperate to have their city number one in something, Detroiters took pride in its bad-ass reputation. T-shirts touted, I Survived a Weekend in Detroit. and I’m So Bad I Vacation in Detroit. The 80’s championship Piston teams were nicknamed the Bad Boys and had an emblem consisting of skull and crossbones. The 1984 movie Beverly Hills Cop contrasted a violent and seedy Detroit with the wealthy and idyllic Beverly Hills, California. The 1987 film RoboCop featured a futuristic Detroit reduced to a virtual wasteland ruled by criminal gangs. Detroit reigned as Murder Capital USA, throughout the 80’s, holding the dubious title more than once.

In 1987 Detroit dedicated a sculpture to native son and heavyweight champion, Joe Louis. It sits in a plaza across from the Detroit City County Building on the riverfront. The bronze sculpture is a fist on the end of a severed arm. For whites the sculpture typified everything they despised about Mayor Young, even though Young did not design the sculpture. The fist was seen as a tasteless embodiment of the black power symbol and a disgrace to Joe Louis. To other Detroiters — black and white — it was just plain ugly. The City also debuted the unimaginatively named People Mover in 1987. The elevated public transit train was over budget, covers a small 2.9-mile loop through the central business district and operates at a loss; 85% of the operating cost is subsidized from the shrinking Detroit city budget.

Throughout the decades I have watched the parade of Detroit institutions leaving the city. The Bob-Lo Boat, Vernor’s Ginger Ale, the Stroh Brewery, Awrey Bakery, Sanders Candy, The London Chop House, Lelli’s, Chrysler Corporation, the Detroit Lions and the Detroit Pistons just to name a few.

When I was a boy growing up on Detroit’s northwest side, Devil’s Night meant soaping windows, egging houses and ringing doorbells. In the modern era Devil’s Night in Detroit has become known nationally for its orgy of arson fires, 840 of them on Devil’s Night 1984. The annual total has since been cut substantially. In 1996, 33,615 city residents answered Mayor Dennis Archer’s call for citizen volunteers to help patrol neighborhoods on Devil’s Night. Arsons were reduced to a still staggering 142, virtually the lowest they have ever been before or since. In the early 90’s while visiting a friend in Los Angeles, I was speaking with a corny lounge singer in an eclectic LA club known as The Dresden. He learned that I was on vacation and asked where I was from. When I told him Detroit, he responded: "Detroit? That town is closed!" It was funny at the time, but not too far from the truth.

When I was a boy growing up on Detroit’s northwest side, Devil’s Night meant soaping windows, egging houses and ringing doorbells. In the modern era Devil’s Night in Detroit has become known nationally for its orgy of arson fires, 840 of them on Devil’s Night 1984. The annual total has since been cut substantially. In 1996, 33,615 city residents answered Mayor Dennis Archer’s call for citizen volunteers to help patrol neighborhoods on Devil’s Night. Arsons were reduced to a still staggering 142, virtually the lowest they have ever been before or since. In the early 90’s while visiting a friend in Los Angeles, I was speaking with a corny lounge singer in an eclectic LA club known as The Dresden. He learned that I was on vacation and asked where I was from. When I told him Detroit, he responded: "Detroit? That town is closed!" It was funny at the time, but not too far from the truth.

One day while driving into the city I decided to drive by my childhood home. The neighborhood had declined, but my old house was holding its own and even had new landscaping. I decided I would ring the bell and introduce myself. The front door had security bars and for a moment I thought that I may have made the largest error in judgment of my life. A man resembling Joe Frazier answered the door, a large dog at his side. I explained that I grew up in the house, was driving by and was curious about the house. After putting his dog away the man returned. "Come on in," he invited, and I did. We introduced ourselves, shook hands, then retired to the kitchen and had a long visit over a cool drink. Mike was curious about the history of the home after learning that my father had the home built in 1947. It all seemed very familiar, although the milk chute of my youth had been welded shut in another sign of the times. We talked about life in the city. Mike let me know I was welcome back anytime.

Several attempts have been made in the last two decades to revive downtown Detroit. It began with the 12 million dollar restoration of the Fox Theatre in 1988, an architectural wonder dating back to 1928. A member of my law school class was in charge of that project. Ten years later a Detroit landmark, the 28 story JL Hudson Department Store, which had been closed since 1983, was demolished in a controlled explosion to make way for the new Campus Martius development. There was the opening of Comerica Park for the Detroit Tigers in 2000 and Ford Field as the new home of the Detroit Lions who moved back into Detroit in 2002.

I had lunch with a good friend from law school the week before opening day at Comerica Park. She had been in charge of the development and expressed concern about how it would be received by Detroiters. I advised her not to worry since there was nothing she could do about it now and pointed out that while sentimentalists would cling for some time to the nostalgic allure of Tiger Stadium new generations would grow up in Detroit with Comerica as their ballpark. Both Ford Field and Comerica are beautiful facilities, but they are both privately owned operations which were subsidized with taxpayer dollars. This was objectionable to many state residents who may never even set foot inside of these facilities and who felt that if the owners were truly committed to the projects they should have completed them without any tax concessions. In the last few years Detroit has hosted the SuperBowl, NCAA Final Four and the MLB All Star Game.

Casinos were approved for Detroit in 1996. While producing tax revenue for an irresponsible government in Lansing, they have not been the boon to downtown businesses that was predicted. Casinos are not in the business of giving away money. Moreover, Casinos make food, drink and entertainment affordable precisely to keep customers from patronizing the very businesses casinos were supposed to benefit. In 2007 MGM Grand opened its permanent casino and hotel location in Detroit at a cost of 800 million dollars. MGM boasts some of the finest restaurants, entertainment, accommodations, spas and shops in the city. MGM did not make this investment to boost its competition.

Also in 2007 the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy opened the first of several phases of a planned waterfront revival. The project has met with strong positive reviews. Another member of my law school class serves as the President and Chief Executive Officer of this project. She admonished me over breakfast recently for not having been to the River Walk and insisted upon taking me on a personal tour. We had a wide-ranging discussion about the state of the city and its future. She implored me to be an ambassador for the city. Neither of us knew thirty years ago that we would be having these discussions.

In the same year that River Walk and MGM Grand opened, I attended the funeral of a friend’s son. My friend lives in the suburbs. Her son was kidnapped, robbed and then executed in one of the hundreds of abandoned homes in Detroit. Jason was white and his assailants were black. Jason was just one of hundreds — mostly black — murdered in the city last year. Also last year another friend of mine was returning from a casino to his car which was parked on a downtown street. Once inside the car he found himself facing a young man who pointed his gun into my friend’s face and demanded that he turn over his car. Unfortunately for this young man, my friend was proficient with a handgun and licensed to carry one. As he opened the door to exit his car my friend shot and killed the criminal. The criminal’s three friends were also armed, but took flight at the sight and sound of the shooting. They were captured by police who came running in response to the sound of gunfire. Oh yes, the incident took place directly across the street from Detroit Police Headquarters in broad daylight. My friend was not charged with a crime. In this case my friend was white and lived in the suburbs and the dead man was black and a resident of Detroit.

That is the other side of the Detroit story. Despite high-profile development within the central business district much of Detroit continues to resemble a third-world country. The absence of law and order — real or perceived — continues to plague the city and keeps many away from living, working or playing in Detroit. Some argue that crime is down in all categories in the last eight years, but that ignores the commensurate drop in population. While the actual number of crimes may have fallen, crime rates have actually risen.

City schools are a disaster both fiscally and in their educational mission. Detroit high schools have the lowest graduation rate in the nation. Young couples who choose to move into new city housing and work downtown ultimately leave when their children become of school age. The city has dozens of school buildings sitting empty and abandoned, but the city school board refuses to consider leasing them to parties interested in opening them as charter schools.

The most severe aspect of city decay is the state of its residential neighborhoods. Home to more than 1,800,000 people in 1954, Detroit’s population has dwindled to less than 900,000 in 2008. An obvious impact of this population drop is that the housing inventory designed for a population of almost 2 million cannot be occupied or maintained by a population which is 53% smaller. The result has been vast tracts of abandoned and rotting housing which have become havens for drug dealers, rapists, murderers and rodents, the targets of thieves and arsonists and a drain on the city tax rolls. The city earns no tax revenue on them and has to use city funds to have them demolished. Worse yet, because those who had the means to leave have left, those who have remained in the city suffer with living in the most impoverished major city in the nation. It is not only homes which sit empty and rotting in the city. Abandoned schools, businesses and industrial sites also blight the landscape. A 1989 study by the Detroit Free Press reported more than 15,000 empty buildings in the city. There are so many vacant lots — an estimated 40,000 — and so few residents to occupy them that plans have been discussed to condense the remaining populace into a contiguous area and clear the abandoned sections. There have even been proposals to convert the empty areas to urban farming. Those who remain in Detroit are like survivors adrift in a leaky lifeboat hoping to be rescued. The issue of race has been eclipsed by the economic plight to which they have been consigned in common.

The old adage says that "you get the government you deserve," but nobody deserves the rabble that passes as Detroit City government these days. Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick has been the subject of a string of scandals and felony charges. It all began with a party held at the taxpayer’s expense in the mayor’s Manoogian Mansion. Reports of drug use and exotic dancers led to an investigation by the Detroit Police Department. The mayor denied that the party ever took place, while the chief of a neighboring police department said he was invited to the party. A dancer who is believed to have performed at the party was mysteriously gunned down in her car before she could testify. When the investigation began closing in on the role of the mayor’s executive protection unit — inexplicably the largest and most expensive of any major city in the nation — in covering up a possible extra-marital affair between Kilpatrick and his Chief of Staff, Christine Beatty, Assistant Chief Gary Brown was suddenly demoted and Officer Harold Nelthrope was deliberately exposed as the informant against the executive protection officers. A subsequent lawsuit by Brown and Nelthrope resulted in a 6 million dollar jury verdict against Kilpatrick and the city. After interest and attorney fees the city ultimately paid out 8.4 million dollars. During the trial Kilpatrick and Beatty denied under oath having had a romantic relationship. A subpoena produced records of their cellular telephone text messages which documented a long and heated relationship. Kilpatrick and Beatty are now facing felony charges, including perjury. While out on bond Kilpatrick physically assaulted two Wayne County Sheriff’s Deputies assigned to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s office when they attempted to serve a subpoena at the home of the mayor’s relative. The mayor was charged with additional felonies arising out that incident, which, if sustained would also violate the conditions of his bond in the perjury case. Apparently, violating bond does not disturb this mayor. Despite bond conditions which restricted his travel, the mayor precipitously departed to Canada in violation of his bond and then lied about and concealed the trip. This is just the mayor. City council members are under federal investigation for accepting bribes to favor a trash-hauling vendor for a city contract. The Detroit Police Department remains under the terms of a consent decree with the Department of Justice as the result of a 2003 federal lawsuit against the city and its police department for corruption. The consent decree gives the DOJ effective trusteeship over the Detroit Police Department’s operations. City services such as street lighting, rubbish removal and emergency services are brutally inefficient. Investigative journalists for local television news regularly feature drinking, theft and other abuses by city employees on the job.

The old adage says that "you get the government you deserve," but nobody deserves the rabble that passes as Detroit City government these days. Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick has been the subject of a string of scandals and felony charges. It all began with a party held at the taxpayer’s expense in the mayor’s Manoogian Mansion. Reports of drug use and exotic dancers led to an investigation by the Detroit Police Department. The mayor denied that the party ever took place, while the chief of a neighboring police department said he was invited to the party. A dancer who is believed to have performed at the party was mysteriously gunned down in her car before she could testify. When the investigation began closing in on the role of the mayor’s executive protection unit — inexplicably the largest and most expensive of any major city in the nation — in covering up a possible extra-marital affair between Kilpatrick and his Chief of Staff, Christine Beatty, Assistant Chief Gary Brown was suddenly demoted and Officer Harold Nelthrope was deliberately exposed as the informant against the executive protection officers. A subsequent lawsuit by Brown and Nelthrope resulted in a 6 million dollar jury verdict against Kilpatrick and the city. After interest and attorney fees the city ultimately paid out 8.4 million dollars. During the trial Kilpatrick and Beatty denied under oath having had a romantic relationship. A subpoena produced records of their cellular telephone text messages which documented a long and heated relationship. Kilpatrick and Beatty are now facing felony charges, including perjury. While out on bond Kilpatrick physically assaulted two Wayne County Sheriff’s Deputies assigned to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s office when they attempted to serve a subpoena at the home of the mayor’s relative. The mayor was charged with additional felonies arising out that incident, which, if sustained would also violate the conditions of his bond in the perjury case. Apparently, violating bond does not disturb this mayor. Despite bond conditions which restricted his travel, the mayor precipitously departed to Canada in violation of his bond and then lied about and concealed the trip. This is just the mayor. City council members are under federal investigation for accepting bribes to favor a trash-hauling vendor for a city contract. The Detroit Police Department remains under the terms of a consent decree with the Department of Justice as the result of a 2003 federal lawsuit against the city and its police department for corruption. The consent decree gives the DOJ effective trusteeship over the Detroit Police Department’s operations. City services such as street lighting, rubbish removal and emergency services are brutally inefficient. Investigative journalists for local television news regularly feature drinking, theft and other abuses by city employees on the job.

Every city needs a viable central business district. However, no number of new entertainment venues will bring Detroit back unless and until basic changes are made to improve education, reduce crime, restore city services and establish political accountability. Some residents criticize the central business district’s revival as being the equivalent of putting a new Easter bonnet on a homeless woman. The required changes will not take place without the commitment of those who left Detroit to live in model communities just outside of the city.

Every city needs a viable central business district. However, no number of new entertainment venues will bring Detroit back unless and until basic changes are made to improve education, reduce crime, restore city services and establish political accountability. Some residents criticize the central business district’s revival as being the equivalent of putting a new Easter bonnet on a homeless woman. The required changes will not take place without the commitment of those who left Detroit to live in model communities just outside of the city.

Those of us who left the city are like residents forced to flee their home in a fire. After getting clear of the threat, they turn to watch with angst the slow destruction of their treasured home and hope against hope that it can be saved and rebuilt. Those who fled will not re-enter or start the rebuilding process until the fire is completely out even if they were responsible for causing the fire in the first place.

Ironically, if there is a metaphor for the city it may lie in its struggling football team. Although the Tigers, Pistons and Red Wings have all captured titles and given Detroiters reason to cheer in recent years it is the Detroit Lions who arouse the strongest passions in Detroiters of all races and economic classes. A listen to Monday morning sports talk radio reveals there is no color barrier when it comes to the Lions. Blacks and whites, suburbanites and city residents are equally passionate about their football team. Detroiters curse the team and its management for their perennial failures and chronic mediocrity, but refuse the obvious urge to abandon their struggling Detroit Lions. Ford Field — where a single ticket can cost several hundred dollars — is packed every Sunday regardless of how many games the team has lost. Detroiters celebrate each victory with pride and see in each win a cause for optimism about the future of their team. In the end this is exactly how Detroiters — living in the city or outside of it — feel about their city.

August 19, 2008