This week saw the mysterious death of yet another journalist in Moscow. This time it was Kommersant columnist Ivan Safronov, a former colonel who wrote about Russia’s ever-murky military affairs, as the Moscow Times reports. Safronov, who occasionally ran afoul of the "security organs" when digging up dirt on Russia’s military-industrial complex (much akin to its American counterpart centered in the north Virginia badlands formerly known as Hell’s Bottom but now called the Pentagon), apparently committed suicide by jumping out of a fifth-floor window, head first, with his hat and coat on. And if you believe that "official" explanation, we have some beachfront property in Nizhny Novgorod we’d like to sell you.

This week saw the mysterious death of yet another journalist in Moscow. This time it was Kommersant columnist Ivan Safronov, a former colonel who wrote about Russia’s ever-murky military affairs, as the Moscow Times reports. Safronov, who occasionally ran afoul of the "security organs" when digging up dirt on Russia’s military-industrial complex (much akin to its American counterpart centered in the north Virginia badlands formerly known as Hell’s Bottom but now called the Pentagon), apparently committed suicide by jumping out of a fifth-floor window, head first, with his hat and coat on. And if you believe that "official" explanation, we have some beachfront property in Nizhny Novgorod we’d like to sell you.

The Western media is emphasizing the fact that Safronov joins a list of some dozen other Russian journalists who have died under mysterious circumstances during the presidency of Vladimir Putin (including real journalists like Anna Politkovskaya and shadowland operatives like Alexander Litvinenko). Although this number is but a fraction of the death toll of journalists in George W. Bush’s satrapy of Iraq, it is of course a disturbing figure.

But let’s not pretend that this kind of thing began under Putin’s reign, with its Bush-like concern for stifling dissent and concentrating power in the name of national security. Scribal life was also cheap during the merry misrule of that unquenchable favorite of Western governments, Boris Yeltsin. (In fact, everyone’s life was pretty cheap in those glorious, gangterish days of yore. And as for anti-democratic draconia, Putin has yet to do anything remotely as radically authoritarian as shelling the democratically elected Duma with tanks and muscling through a dubious (and probably bogus) referendum granting himself and future presidents the wide-ranging powers that Putin now employs with considerably greater skill than his drunken mentor.)

During my first stint at the Moscow Times in 1994, another reporter who made a specialty of investigating the rampant corruption in Yeltsin’s armed forces was blown up in his office at Moskovsky Komsomolets, just across the street from our building. Dmitry Kholodov was killed when he opened a package that an informant had told him contained evidence of military malfeasance. There followed a great outpouring of crocodile tears from Yeltsin and the top military brass implicated in many of Kholodov’s stories. His killing was officially upgraded from ordinary murder to a case of "terrorism," to be given the highest attention by every investigative tool at the state’s command. Years later, in 2004, six army officers were finally tried for the murder — and acquitted. Kholodov’s killing remains officially unsolved. But at least they didn’t say he blew himself up on purpose.

Kholodov was just one of the several journalists who met their final deadline with Uncle Borya in the Kremlin. This is a particular hazard of those who delve into military matters, like Safronov. The Russian military, like its American counterpart, is a vast, amorphous, many-headed hydra, with numerous secret units, criminal enterprises and rogue operators, all of them well-armed and many of them trained in the blackest covert arts. One needn’t automatically assume that presidential orders (or knowledge) are required to instigate the murder of a reporter disturbing some well-feathered military nest somewhere.

On the other hand, the window -drop "suicide" does have a well-established official pedigree — and not just in Russia. When I first read of Safronov’s death, I immediately thought of a similar case involving the death of an American scientist who had uncovered Nazi-style medical experiments on prisoners and tests of LSD and other mind-altering drugs on unsuspecting targets. He too "committed suicide" by somehow hurtling himself through a glass window from a hotel room, while in the company of a CIA handler. The government cover-up of his death continued for decades, and was assisted, years after the death, by the knowing deception of two top presidential aides: Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfeld.

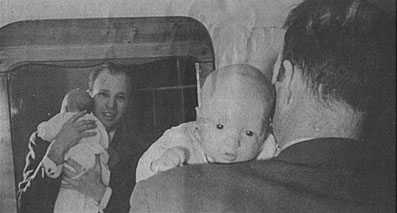

I wrote about the case of Frank Olson for CounterPunch in 2002. The story traces "the thin red cord that weaves in and out of the shifting facades of reason and respectability that mask the brutal machinery of power. At certain rare moments the thread flashes into sight, emerging from the chaotic jumble of unbearable truth and life-giving illusion that makes up human reality." One emergence was the Frank Olson case, which had been kept alive by his son, Eric [shown in a childhood photo with Frank below], who for half a century tried to find out what happened to his father on that fatal night in 1953. As I wrote then:

Frank’s son, Eric, believes he knows the answer now: his father was murdered to keep the thread from sight, to "protect" the American people from the knowledge that their own government had taken up and extended Nazi experiments on mind control, psychological torture and chemical warfare — and that it was conducting these experiments as the Nazis did, on unwilling subjects, on captives and "expendables," even to the point of "termination."

Frank’s son, Eric, believes he knows the answer now: his father was murdered to keep the thread from sight, to "protect" the American people from the knowledge that their own government had taken up and extended Nazi experiments on mind control, psychological torture and chemical warfare — and that it was conducting these experiments as the Nazis did, on unwilling subjects, on captives and "expendables," even to the point of "termination."

Frank Olson was a CIA scientist at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the Army’s biological weapons research center. Ostensibly he was a civilian employee of the Army; his family didn’t know his true employer. Olson worked on methods of spreading anthrax and other toxins; some of his colleagues were involved in mind control drugs and torture techniques. But his life within the charmed circle of the American intelligence elite would unravel with dizzying speed in just a few months in 1953.

It began in the summer of that year, when Olson made several trips to Europe, to investigate secret American-British research centers in Germany. There he found the CIA was testing "truth serums" and other torture drugs on "expendables," including captured Russian agents. He told a British colleague that he had witnessed "horrors" there — horrors which called into starkest question his own work on biochemical weapons. He came home a changed man, troubled, morose. He told his wife he wanted to leave government service.

But it was too late: the brutal machinery was already grinding. His British colleague told his own superiors about Olson’s concerns; they in turn informed the CIA that Olson was now a "security risk." Not long after his return, Olson given LSD by one of his colleagues — slipped into his drink as part of a covert "field experiment." A few days later, he was flown to New York, ostensibly for psychiatric treatment at the hands of a CIA doctor — who prescribed whiskey and pills. Then he was taken to a CIA magician — yes, a magician — who apparently tried to hypnotize him for interrogation.

Finally he checked into a cheap hotel — with a CIA handler, Robert Lashbrook, in tow. Olson called his wife, told her he was feeling better and would be home the next day. But that night, he was found dead on the street, 10 floors below. The handler said that Olson had apparently thrown himself through the closed window in a suicidal fit. The government told the family it was simply a tragic suicide. They didn’t mention the LSD — or the fact that Olson worked for the CIA.

It would take Eric Olson 49 years to piece together as much of the truth as we are ever likely to know about what happened that night. But first would come a false dawn, a cruel trick played on the family by cynical operators in Ford Administration, who used a screen of half-truth and deliberate falsehood to divert the Olsons — and the nation — from the darkest tangles of the thread. Two of those operators would work the thread — play upon it, thrive on it, hold hard to its damp crimson stain — to rise from the obscurity of White House functionaries to positions of colossal, world-shaking power:

Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld.

(The complete story, with annotations, can be found here: The Secret Sharers: The CIA, the Bush Gang, and the Killing of Frank Olson.)

So let us lay not that flattering unction to our souls, that such mysterious deaths and defenestrations occur only in the mephitic air of Putin’s Moscow. Inconvenient people — especially those persistent enough to be a bother but not powerful or connected enough to protect themselves from reprisal — are removed from the scene, one way or another, all the time. Gangsters do it; terrorists do it; and so do agents of the state, "rogue" or otherwise.