Freedom watch does freezergate After years of playing dead while the gang of outlaws running the White House routinely invaded the privacy of mere citizens without statutory authorization ("Bush's Real Motive," News and Features, February 10), Congress was finally roused by executive aggression against one of its own last week. That's nice, except the dolts in Congress let the imperial presidency get so out of hand that we are now faced with a truly nasty constitutional crisis. It's one that is far more complex than anyone in government, academia, or the press seems to realize.

Freedom watch does freezergate After years of playing dead while the gang of outlaws running the White House routinely invaded the privacy of mere citizens without statutory authorization ("Bush's Real Motive," News and Features, February 10), Congress was finally roused by executive aggression against one of its own last week. That's nice, except the dolts in Congress let the imperial presidency get so out of hand that we are now faced with a truly nasty constitutional crisis. It's one that is far more complex than anyone in government, academia, or the press seems to realize.

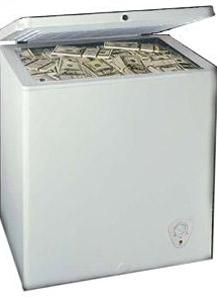

When the FBI's search of Louisiana Democratic Representative William Jefferson's Capitol Hill office ignited a firestorm led by the formerly bootlicking House Republican leadership, Bush and Co. appeared surprised. After all, they thought they had the goods on Jefferson, who had already been caught on an FBI-sting video accepting $100,000 in cash, suspected to be a bribe. And there was no love lost for the Louisiana Democrat, as House minority leader Nancy Pelosi herself made clear when she insisted publicly that Jefferson relinquish his seat on the Ways and Means Committee (Jefferson refused). The FBI had even gone to the trouble of getting the personal okay of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, in addition to a court-ordered warrant, to pursue their little fishing expedition.

What the White House didn't count on was that a red-hot Congress would invoke an obscure constitutional provision called the "speech or debate clause," found in Article 1, Section 6, that protects the legislature from intrusion by other branches of government under certain circumstances. Under its terms, it is likely that the Department of Justice was required, at the very least, to ask the House leadership for permission to execute the warrant and to allow an observer appointed by the House to monitor the intrusion on Jefferson's office. The provision is nothing less than a bulwark of the separation-of-powers doctrine, derived from ancient parliamentary restrictions on English kings. It accounts for why the executive branch has never before in the Republic's history dared to search a member of Congress's office.

A host of "scholars" have been uncritically quoted in the press arguing that the speech or debate clause does not apply here. Well, they're simply wrong – not least because they insist, incorrectly, on drawing analogies between this case and Watergate. In the Watergate case, the Supreme Court ruled that executive privilege did not protect Nixon from having to turn over White House tapes to a congressionally appointed special prosecutor, who had requested them through subpoena. However, there's a world of difference between proceeding by subpoena and conducting an FBI raid, which gives agents access to all manner of confidential legislative materials sitting in the Congress member's office. Moreover, in the Nixon-tapes case, a very careful process was set up by which the tapes were listened to. In the Jefferson case, FBI agents were there in the office alone, rummaging through the congressman's papers, the overwhelming bulk of which surely related to his constitutionally protected legislative activities rather than to any bribery scheme. Besides, the concept of "executive privilege" is not in the Constitution. Rather, it's a court-made construct of limited scope, so it offered flimsy grounds for Nixon's case – unlike Congress's reliance on the speech or debate clause that, although narrowly limited to the protection of legislative activities, would almost certainly prohibit Bush's unrestricted meddling with Jefferson's papers.

In the early 1970s, I was co-counsel for then-senator Mike Gravel (D-Alaska) in his court challenge to the Nixon administration's subpoena seeking Gravel's copy of the Pentagon Papers. Even Nixon and his thuggish attorney general, John N. Mitchell (who ended up serving a well-earned prison sentence for perjury, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy), did not have the temerity to conduct a search of Gravel's senatorial office in hopes of finding his copy of the Pentagon Papers. A search, after all, is one giant step more intrusive than a subpoena that simply demands that the congressman produce the document. Nixon and Mitchell did not even subpoena Gravel directly, fearful of transgressing the clause. Instead, they subpoenaed one of the senator's aides, but Gravel intervened to argue that the subpoena was an intrusion by the executive branch into his official work. Even the subpoena caused a firestorm, and the Senate joined the Supreme Court fight on behalf of legislative privilege. The court was unanimous in ruling that the clause protected all legislative activities, but Gravel lost his effort to overturn the subpoena by a single vote because of the manner in which he'd processed the papers. Had the FBI raided Gravel's office, it would have likely shown up in the bill of impeachment being drawn up at the time Nixon resigned the presidency.

Bush announced a 45-day cooling-off period during which the seized documents will be held but not read by the solicitor general while the Department of Justice tries to work out a plan with the House leadership. Attorney General Gonzales and FBI director Robert Mueller, who don't seem to understand the meaning and scope of the clause (any more than do most legal commentators being quoted in the press), have threatened to resign if the documents are returned. But if they really grasped the scale of the constitutional insult the administration has hurled at Congress, they might have instead suggested that House counsel share custody of the Jefferson papers with the Solicitor General. This would be in the spirit of their constitutional obligation to Congress's right to protect the people's legislative business from royalist snoops.

June 3, 2006

Harvey A. Silverglate [send him mail], co-author of The Shadow University, is an attorney with Boston's Good & Cormier. This article, from the Boston Phoenix, is reprinted with permission.