In the Vietnam era, the subject of war crimes was the last to arrive and the first to depart. When, in 1971 in Detroit, Vietnam Veterans Against the War convened its Winter Soldier Investigation into U.S. war crimes in Southeast Asia, it was roundly ignored by the media. Over 100 veterans gave firsthand testimony to war crimes they either committed or witnessed. Beyond the unbearable nature of their testimony, the hearings were startling for the fact that here were men who yearned to take some responsibility for what they had done. But while it was, by then, possible for Americans to accept the GI as a victim in Vietnam, it proved impossible for most Americans to accept him as a human being taking responsibility for a crime against humanity. There was no place for this in the American imagination, it seemed, no less for the thought that the planning and prosecution of the war were potential crimes committed by our leaders. Evidently there still is none, which is why it’s important to follow Noam Chomsky back into the Iraq of recent years to consider the American occupation of that country in the context of war crimes.

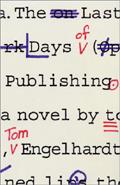

The piece that follows is an excerpt from Chomsky’s new book, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy, which is officially published on this very day. It is Chomsky at his best, a superb tour (de force) of a world in which the Bush administration has regularly asserted its right to launch “preventive” military interventions against “failed” and “rogue” states, while increasingly taking on the characteristics of those failed and rogue states itself. It will be an indispensable volume for any library. (You can check out a Chomsky discussion of it at Democracy Now!) ~ Tom

Returning to the Scene of the Crime

By Noam Chomsky

This piece is adapted from Chapter 2 of Noam Chomsky’s newest book, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

This piece is adapted from Chapter 2 of Noam Chomsky’s newest book, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

In 2002, White House counsel Alberto Gonzales passed on to Bush a memorandum on torture by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC). As noted by constitutional scholar Sanford Levinson: “According to the OLC, u2018acts must be of an extreme nature to rise to the level of torture… Physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.'” Levinson goes on to say that in the view of Jay Bybee, then head of the OLC, “The infliction of anything less intense than such extreme pain would not, technically speaking, be torture at all. It would merely be inhuman and degrading treatment, a subject of little apparent concern to the Bush administration’s lawyers.”

Gonzales further advised President Bush to effectively rescind the Geneva Conventions, which, despite being “the supreme law of the land” and the foundation of contemporary international law, contained provisions Gonzales determined to be “quaint” and “obsolete.” Rescinding the conventions, he informed Bush, “substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal prosecution under the War Crimes Act.” Passed in 1996, the act carries severe penalties for “grave breaches” of the conventions: the death penalty, “if death results to the victim” of the breach. Gonzales was later appointed to be attorney general and would probably have been a Supreme Court nominee if Bush’s constituency did not regard him as “too liberal.”

How to Destroy a City to Save It

Gonzales’s legal advice about protecting Bush from the threat of prosecution under the War Crimes Act was proven sound not long after he gave it, in a case far more severe even than the torture scandals. In November 2004, U.S. occupation forces launched their second major attack on the city of Falluja. The press reported major war crimes instantly, with approval. The attack began with a bombing campaign intended to drive out all but the adult male population; men ages fifteen to forty-five who attempted to flee Falluja were turned back. The plans resembled the preliminary stage of the Srebrenica massacre, though the Serb attackers trucked women and children out of the city instead of bombing them out. While the preliminary bombing was under way, Iraqi journalist Nermeen al-Mufti reported from “the city of minarets [which] once echoed the Euphrates in its beauty and calm [with its] plentiful water and lush greenery… a summer resort for Iraqis [where people went] for leisure, for a swim at the nearby Habbaniya lake, for a kebab meal.” She described the fate of victims of these bombing attacks in which sometimes whole families, including pregnant women and babies, unable to flee, along with many others, were killed because the attackers who ordered their flight had cordoned off the city, closing the exit roads.

Al-Mufti asked residents whether there were foreign fighters in Falluja. One man said that “he had heard that there were Arab fighters in the city, but he never saw any of them.” Then he heard that they had left. “Regardless of the motives of those fighters, they have provided a pretext for the city to be slaughtered,” he continued, and “it is our right to resist.” Another said that “some Arab brothers were among us, but when the shelling intensified, we asked them to leave and they did,” and then asked a question of his own: “Why has America given itself the right to call on UK and Australian and other armies for help and we don’t have the same right?”

It would be interesting to ask how often that question has been raised in Western commentary and reporting. Or how often the analogous question was raised in the Soviet press in the 1980s, about Afghanistan. How often was a term like “foreign fighters” used to refer to the invading armies? How often did reporting and commentary stray from the assumption that the only conceivable question is how well “our side” is doing, and what the prospects are for “our success”? It is hardly necessary to investigate. The assumptions are cast in iron. Even to entertain a question about them would be unthinkable, proof of “support for terror” or “blaming all the problems of the world on America/Russia,” or some other familiar refrain.

After several weeks of bombing, the United States began its ground attack in Falluja. It opened with the conquest of the Falluja General Hospital. The front-page story in the New York Times reported that “patients and hospital employees were rushed out of rooms by armed soldiers and ordered to sit or lie on the floor while troops tied their hands behind their backs.” An accompanying photograph depicted the scene. It was presented as a meritorious achievement. “The offensive also shut down what officers said was a propaganda weapon for the militants: Falluja General Hospital, with its stream of reports of civilian casualties.” Plainly such a propaganda weapon is a legitimate target, particularly when “inflated civilian casualty figures” — inflated because our leader so declared — had “inflamed opinion throughout the country, driving up the political costs of the conflict.” The word “conflict” is a common euphemism for U.S. aggression, as when we read on the same pages that “now, the Americans are rushing in engineers who will begin rebuilding what the conflict has just destroyed” — just “the conflict,” with no agent, like a hurricane.

Some relevant documents passed unmentioned, perhaps because they too are considered quaint and obsolete: for example, the provision of the Geneva Conventions stating that “fixed establishments and mobile medical units of the Medical Service may in no circumstances be attacked, but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict.” Thus the front page of the world’s leading newspaper was cheerfully depicting war crimes for which the political leadership could be sentenced to severe penalties under U.S. law, the death penalty if patients ripped from their beds and manacled on the floor happened to die as a result. The questions did not merit detectable inquiry or reflection. The same mainstream sources told us that the U.S. military “achieved nearly all their objectives well ahead of schedule,” as “much of the city lay in smoking ruins.” But it was not a complete success. There was little evidence of dead “packrats” in their “warrens” or on the streets, “an enduring mystery.” US forces did discover “the body of a woman on a street in Falluja, but it was unclear whether she was an Iraqi or a foreigner.” The crucial question, apparently.

Another front-page story quotes a senior Marine commander who says that the attack on Falluja “ought to go down in the history books.” Perhaps it should. If so, we know on just what page of history it will find its place. Perhaps Falluja will appear right alongside Grozny [the destroyed capital of Chechnya], a city of about the same size, with a picture of Bush and Putin gazing into each other’s souls. Those who praise or for that matter even tolerate all of this can select their own favorite pages of history.

A Burnt-Out Shell of a Country

The media accounts of the assault were not uniform. Qatar-based Al-Jazeera, the most important news channel in the Arab world, was harshly criticized by high U.S. officials for having “emphasized civilian casualties” during the destruction of Falluja. The problem of independent media was later resolved when the channel was kicked out of Iraq in preparation for free elections.

Turning beyond the U.S. mainstream, we discover also that “Dr. Sami al-Jumaili described how U.S. warplanes bombed the Central Health Centre in which he was working,” killing thirty-five patients and twenty-four staff. His report was confirmed by an Iraqi reporter for Reuters and the BBC, and by Dr. Eiman al-Ani of Falluja General Hospital, who said that the entire health center, which he reached shortly after the attack, had collapsed on the patients. The attacking forces said that the report was “unsubstantiated.” In another gross violation of international humanitarian law, even minimal decency, the U.S. military denied the Iraqi Red Crescent access to Falluja. Sir Nigel Young, the chief executive of the British Red Cross, condemned the action as “hugely significant.” It sets “a dangerous precedent,” he said: “The Red Crescent had a mandate to meet the needs of the local population facing a huge crisis.” Perhaps this additional crime was a reaction to a very unusual public statement by the International Committee of the Red Cross, condemning all sides in the war in Iraq for their “utter contempt for humanity.”

In what appears to be the first report of a visitor to Falluja after the operation was completed, Iraqi doctor Ali Fadhil said he found it “completely devastated.” The modern city now “looked like a city of ghosts.” Fadhil saw few dead bodies of Iraqi fighters in the streets; they had been ordered to abandon the city before the assault began. Doctors reported that the entire medical staff had been locked into the main hospital when the U.S. attack began, “tied up” under US orders: “Nobody could get to the hospital and people were bleeding to death in the city.” The attitudes of the invaders were summarized by a message written in lipstick on the mirror of a ruined home: “F__k Iraq and every Iraqi in it.” Some of the worst atrocities were committed by members of the Iraqi National Guard used by the invaders to search houses, mostly “poor Shias from the south… jobless and desperate,” probably “fan[ning] the seeds of a civil war.”

Embedded reporters arriving a few weeks later found some people “trickling back to Falluja,” where they “enter a desolate world of skeletal buildings, tank-blasted homes, weeping power lines and severed palm trees.” The ruined city of 250,000 was now “devoid of electricity, running water, schools or commerce,” under a strict curfew, and “conspicuously occupied” by the invaders who had just demolished it and the local forces they had assembled. The few refugees who dared to return under tight military surveillance found “lakes of sewage in the streets. The smell of corpses inside charred buildings. No water or electricity. Long waits and thorough searches by US troops at checkpoints. Warnings to watch out for land mines and booby traps. Occasional gunfire between troops and insurgents.”

Half a year later came perhaps the first visit by an international observer, Joe Carr of the Christian Peacemakers Team in Baghdad, whose previous experience had been in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories. Arriving on May 28, he found painful similarities: many hours of waiting at the few entry points, more for harassment than for security; regular destruction of produce in the devastated remains of the city where “food prices have dramatically increased because of the checkpoints”; blocking of ambulances transporting people for medical treatment; and other forms of random brutality familiar from the Israeli press. The ruins of Falluja, he wrote, are even worse than Rafah in the Gaza Strip, virtually destroyed by US-backed Israeli terror. The United States “has leveled entire neighborhoods, and about every third building is destroyed or damaged.” Only one hospital with in-patient care survived the attack, but access was impeded by the occupying army, leading to many deaths in Falluja and rural areas. Sometimes dozens of people were packed into a “burned out shell.” Only about a quarter of families whose homes were destroyed received some compensation, usually less than half of the cost for materials needed to rebuild them.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, accused US and British troops in Iraq of “breaching international law by depriving civilians of food and water in besieged cities as they try to flush out militants” in Falluja and other cities attacked in subsequent months. US-led forces “cut off or restricted food and water to encourage residents to flee before assaults,” he informed the international press, “using hunger and deprivation of water as a weapon of war against the civilian population, [in] flagrant violation” of the Geneva Conventions. The U.S. public was largely spared the news.

Even apart from such major war crimes as the assault on Falluja, there is more than enough evidence to support the conclusion of a professor of strategic studies at the Naval War College that the year 2004 “was a truly horrible and brutal one for hapless Iraq.” Hatred of the United States, he continued, is now rampant in a country subjected to years of sanctions that had already led to “the destruction of the Iraqi middle class, the collapse of the secular educational system, and the growth of illiteracy, despair, and anomie [that] promoted an Iraqi religious revival [among] large numbers of Iraqis seeking succor in religion.” Basic services deteriorated even more than they had under the sanctions. “Hospitals regularly run out of the most basic medicines… the facilities are in horrid shape, [and] scores of specialists and experienced physicians are leaving the country because they fear they are targets of violence or because they are fed up with the substandard working conditions.”

Meanwhile, “religion’s role in Iraqi political life has ratcheted steadily higher since US-led forces overthrew Mr. Hussein in 2003,” the Wall Street Journal reports. Since the invasion, “not a single political decision” has been made without Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s “tacit or explicit approval, say government officials,” while the “formerly little-known young rebel cleric” Muqtada al-Sadr has “fashioned a political and military movement that has drawn tens of thousands of followers in the south and in Baghdad’s poorest slums.”

Similar developments have taken place in Sunni areas. The vote on Iraq’s draft constitution in fall 2005 turned into “a battle of the mosques,” with voters largely following religious edicts. Few Iraqis had even seen the document because the government had scarcely distributed any copies. The new constitution, the Wall Street Journal notes, has “far deeper Islamic underpinnings than Iraq’s last one, a half century ago, which was based on [secular] French civil law,” and had granted women “nearly equal rights” with men. All of this has now been reversed under the U.S. occupation.

War Crimes and Casualty Counts

The consequences of years of Western violence and strangulation are endlessly frustrating to civilized intellectuals, who are amazed to discover that, in the words of Edward Luttwak, “the vast majority of Iraqis, assiduous mosque-goers and semi-literate at best,” are simply unable to “believe what for them is entirely incomprehensible: that foreigners have been unselfishly expending their own blood and treasure to help them.” By definition, no evidence necessary.

Commentators have lamented that the United States has changed “from a country that condemned torture and forbade its use to one that practices torture routinely.” The actual history is far less benign. But torture, however horrifying, scarcely weighs in the balance in comparison with the war crimes at Falluja and elsewhere in Iraq, or the general effects of the U.S. and UK invasion. One illustration, noted in passing and quickly dismissed in the United States, is the careful study by prominent U.S. and Iraqi specialists published in the world’s leading medical journal, the Lancet, in October 2004. The conclusions of the study, carried out on rather conservative assumptions, are that “the death toll associated with the invasion and occupation of Iraq is probably about 100,000 people, and may be much higher.” The figures include nearly 40,000 Iraqis killed as a direct result of combat or armed violence, according to a later Swiss review of the study’s data. A subsequent study by Iraq Body Count found 25,000 noncombatants reported killed in the first two years of the occupation — in Baghdad, one in 500 citizens; in Falluja, one in 136. U.S.-led forces killed 37%, criminals 36%, “anti-occupation forces” 9%. Killings doubled in the second year of the occupation. Most deaths were caused by explosive devices; two-thirds of these by air strikes. The estimates of Iraq Body Count are based on media reports, and are therefore surely well below the actual numbers, though shocking enough.

Reviewing these reports along with the UNDP “Iraq Living Conditions Survey” (April 2005), British analyst Milan Rai concludes that the results are largely consistent, the apparent variation in numbers resulting primarily from differences in the specific topics investigated and the time periods covered. These conclusions gain some support from a Pentagon study that estimated 26,000 Iraqi civilians and security forces killed and wounded by insurgents since January 2004. The New York Times report of the Pentagon study also mentions several others, but omits the most important one, in the Lancet. It notes in passing that “no figures were provided for the number of Iraqis killed by American-led forces.” The Times story appeared immediately after the day that had been set aside by international activists for commemoration of all Iraqi deaths, on the first anniversary of the release of the Lancet report.

The scale of the catastrophe in Iraq is so extreme that it can barely be reported. Journalists are largely confined to the heavily fortified Green Zone in Baghdad, or else travel under heavy guard. There have been a few regular exceptions in the mainstream press, such as Robert Fisk and Patrick Cockburn [of the British newspaper The Independent], who face extreme hazards, and there are occasional indications of Iraqi opinion. One was a report on a nostalgic gathering of educated westernized Baghdad elites, where discussion turned to the sacking of Baghdad by Hulagu Khan and his vicious atrocities. A philosophy professor commented that “Hulagu was humane compared with the Americans,” drawing some laughter, but “most of the guests seemed eager to avoid the subject of politics and violence, which dominate everyday life here.” Instead they turned to past efforts to create an Iraqi national culture that would overcome the old ethnic-religious divisions to which Iraq is now “regressing” under the occupation, and discussed the destruction of the treasures of Iraqi and world civilization, a tragedy not experienced since the Mongol invasions.

Additional effects of the invasion include the decline of the median income of Iraqis, from $255 in 2003 to about $144 in 2004, as well as “significant countrywide shortages of rice, sugar, milk, and infant formula,” according to the UN World Food Program, which had warned in advance of the invasion that it would not be able to duplicate the efficient rationing system that had been in place under Saddam Hussein. Iraqi newspapers report that new rations contain metal filings, one consequence of the vast corruption under the U.S.-UK occupation. Acute malnutrition doubled within sixteen months of the occupation of Iraq, to the level of Burundi, well above Haiti or Uganda, a figure that “translates to roughly 400,000 Iraqi children suffering from u2018wasting,’ a condition characterized by chronic diarrhea and dangerous deficiencies of protein.” This is a country in which hundreds of thousands of children had already died as a consequence of the U.S.- and UK-led sanctions. In May 2005, UN rapporteur Jean Ziegler released a report of the Norwegian Institute for Applied Social Science confirming these figures. The relatively high nutritional levels of Iraqis in the 1970s and 1980s, even through the war with Iran, began to decline severely during the decade of the sanctions, with a further disastrous decline after the 2003 invasion.

Meanwhile, violence against civilians extended beyond the occupiers and the insurgency. Washington Post reporters Anthony Shadid and Steve Fainaru reported that “Shiite and Kurdish militias, often operating as part of Iraqi government security forces, have carried out a wave of abductions, assassinations and other acts of intimidation, consolidating their control over territory across northern and southern Iraq and deepening the country’s divide along ethnic and sectarian lines.” One indicator of the scale of the catastrophe is the huge flood of refugees “fleeing violence and economic troubles,” a million to Syria and Jordan alone since the US invasion, most of them “professionals and secular moderates who could help with the practical task of getting the country to run well.”

The Lancet study estimating 100,000 probable deaths by October 2004 elicited enough comment in England that the government had to issue an embarrassing denial, but in the United States virtual silence prevailed. The occasional oblique reference usually describes it as the “controversial” report that “as many as 100,000” Iraqis died as a result of the invasion. The figure of 100,000 was the most probable estimate, on conservative assumptions; it would be at least as accurate to describe it as the report that “as few as 100,000” died. Though the report was released at the height of the U.S. presidential campaign, it appears that neither of the leading candidates was ever publicly questioned about it.

The Lancet study estimating 100,000 probable deaths by October 2004 elicited enough comment in England that the government had to issue an embarrassing denial, but in the United States virtual silence prevailed. The occasional oblique reference usually describes it as the “controversial” report that “as many as 100,000” Iraqis died as a result of the invasion. The figure of 100,000 was the most probable estimate, on conservative assumptions; it would be at least as accurate to describe it as the report that “as few as 100,000” died. Though the report was released at the height of the U.S. presidential campaign, it appears that neither of the leading candidates was ever publicly questioned about it.

The reaction follows the general pattern when massive atrocities are perpetrated by the wrong agent. A striking example is the Indochina wars. In the only poll (to my knowledge) in which people were asked to estimate the number of Vietnamese deaths, the mean estimate was 100,000, about 5% of the official figure; the actual toll is unknown, and of no more interest than the also unknown toll of casualties of U.S. chemical warfare. The authors of the study comment that it is as if college students in Germany estimated Holocaust deaths at 300,000, in which case we might conclude that there are some problems in Germany — and if Germany ruled the world, some rather more serious problems.

The reaction follows the general pattern when massive atrocities are perpetrated by the wrong agent. A striking example is the Indochina wars. In the only poll (to my knowledge) in which people were asked to estimate the number of Vietnamese deaths, the mean estimate was 100,000, about 5% of the official figure; the actual toll is unknown, and of no more interest than the also unknown toll of casualties of U.S. chemical warfare. The authors of the study comment that it is as if college students in Germany estimated Holocaust deaths at 300,000, in which case we might conclude that there are some problems in Germany — and if Germany ruled the world, some rather more serious problems.

Readers who wish to check the sources for information and quotes in this piece are directed to Noam Chomsky’s new book, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

Reprinted by permission of Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.