The response to President Bush's latest budget proposal showed how the system works in Washington. The welfare state not only collects and redistributes hundreds of billions of dollars, but is rigged to set off alarm bells the minute anyone proposes to reduce the dollars redistributed. Even if the amounts are increased by less than the inflation rate that is considered to be a cruel and heartless thing. Sirens and bells will start their clamor. Agencies threatened with any kind of a cut command the prompt attention and sympathy of the same editors and headline writers who had previously been complaining about budget deficits.

The response to President Bush's latest budget proposal showed how the system works in Washington. The welfare state not only collects and redistributes hundreds of billions of dollars, but is rigged to set off alarm bells the minute anyone proposes to reduce the dollars redistributed. Even if the amounts are increased by less than the inflation rate that is considered to be a cruel and heartless thing. Sirens and bells will start their clamor. Agencies threatened with any kind of a cut command the prompt attention and sympathy of the same editors and headline writers who had previously been complaining about budget deficits.

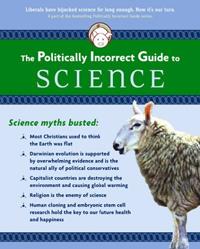

Consider the science field, which I have been following since writing The Politically Incorrect Guide to Science [Regnery, 2005]. In some instances, the Administration proposes to increase spending by less than inflation. That is called a cut. The overall budget of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Md., was actually doubled by Congress over a five-year period ending in 2003. Today, that budget stands at $28,600,000,000. Under the new budget that huge number will remain unchanged. And the budget of the National Science Foundation, which funds the research of mathematicians, physicists, chemists, biologists and computer scientists galore at many universities, will be raised to $6 billion. That is an increase of 7.8 percent over the previous year.

Here is how Science magazine headlined its story on these developments: "NIH Shrinks, NSF Crawls as Congress Finishes Spending Bills." A chart accompanying the article showed the dramatic dollar increases that the NIH has enjoyed in recent years. Its overall budget was only about $6 billion as recently as 1986. But the scientists who live so comfortably at the taxpayers' expense have grown accustomed to their luxuries and perquisites. Annual budget increases have for years exceeded eight percent on average.

So the latest failure to increase the overall total was construed as a cut and a slap in the face. Referring to the "gloomy 2006 budget news," Science lamented that the agency "is falling behind inflation." For the editors of that magazine, week after week, the protection of scientists' ready access to taxpayers' money is the dominant concern.

Consider the National Cancer Institute, one of the 19 institutes that comprise the NIH. The New York Times reported that “Mr. Bush is seeking $4.75 billion for the National Cancer Institute, which is $40 million less than its current budget.” So the NCI budget (perhaps) will go from $4,790,000,000 to $4,750,000,000. The next day, the Washington Post ran on its op-ed page a piece headlined "Cancer Research in Danger." It was written by officials of the Johns Hopkins University cancer center that receives funds directly from the National Cancer Institute. A piece of undiluted propaganda, it praised the NIH as a "formidable economic engine that powers the country's scientific advances." Furthermore, it "hands out grants to more than 212,000 investigators at more than 2,800 universities, medical schools and other research institutions." The article lavished praise on specific grant recipients at John Hopkins's cancer center, including one who is said to be the "world's most cited researcher over a 20-year span."

If we discount the improvement in cancer mortality due to the reduction in smoking, there is little evidence that the research undertaken at vast expense to the taxpayers since President Nixon's War on Cancer has done any good. A strong statistical association between smoking and lung cancer was established about 40 years ago by British researchers. The U.S. War on Cancer began in 1971 and was supposed to have been won by 1976. About 557,000 Americans died of cancer in 2003, a decrease of 369 from the year before, attributable to a continued decline in smoking. In 1971, 330,000 Americans died of cancer.

Incidentally, only one of the 19 NIH institutes received a budget increase, and that was the National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This is the agency that "is leading research on bird flu and biological terrorism," as the Times pointed out. Ah, the budgetary implications of public-health scares. The institute is headed by Anthony Fauci, who has headed up NIAID for decades and was a key player in convincing the nation that AIDS is a disease that puts us "all at risk," thereby paving the way for massive funding increases to combat that much hyped threat.

When it comes to government budgeting, hardly anyone dares to challenge the equation: “More money ensures more progress toward achieving the stated goal of the agency.” The efficacy of budget increases is an unquestioned article of faith in Washington. The one area where some murmured doubts have been heard is the field of public education. Testing can give rise to scores and therefore quantification. SAT scores have shown a strong inverse correlation with funding, and this alone is sufficient to tell us why the teachers unions who profit from government funding dislike testing.

Perhaps, today, some enterprising researcher would care to quantify the changes in the nation's health since the NIH enjoyed its enormous budgetary increases. But I doubt that any such proposal would be funded by the government.

February 11, 2006