Have you ever noticed that some participants in America's greatest calamity, its War Between the States, are quite familiar to us? Meanwhile, many others of that eventful age are ignored or likely no longer even known by those academics who are the gatekeepers of our national memory. Among the forgotten are the American Indians of the Five "Civilized" Tribes – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole – most of whom fought for the Confederacy.

Few participants in that war exhibited greater courage, or suffered greater loss, than these long-forgotten patriots, whose blood kin included such distinguished personages as the great Sequoyah (George Gist), who committed the Cherokee language into an alphabet. Their lands and communities in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), growing and prosperous before the War of 1861–65, lay in rubble and ruin afterwards. These Indians, many of them slaveowners, fit none of the customary American history stereotypes. Throughout their lives, they adhered to many of the core values of America's Founding Fathers, including a devotion to the Christian faith; commitment to an excellent education distinguished by classical and scriptural distinctives; belief in self-reliant labors and the possession and cultivation of private property; support of the practices of limited government – especially on the national level – and separated powers; and the principles of free market economics, and the creativity and innovation incumbent in that.

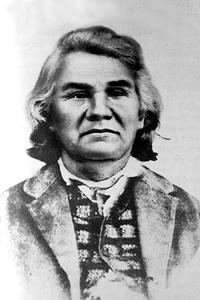

Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Such a man was three-quarter-Cherokee Stand Watie, the only Indian to attain the rank of general in either the Federal or Confederate armies. Born in 1806 near Rome, Georgia, and educated at a Christian church mission school in Tennessee, Watie proved himself a leader even as a young man. A frequent correspondent in the 1830s with President Andrew Jackson (not to be confused with Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson), he recognized that man's determination to proceed with the ethnic cleansing of the Cherokees from the southeastern United States. For instance, when uninvited white gold-seekers flooded Cherokee land in north Georgia in the early 1830s, the United States Supreme Court ordered the state to protect the mostly-Christian tribe and let them live in peace on their own land. President Jackson famously responded: "The Chief Justice [John Marshall] has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it."

So Stand Watie, divining the imminent slaughter of his people if they did not leave, and seeking to craft the best possible arrangement for them, helped negotiate the 1835 New Echota Treaty between the United States and the Cherokee Nation to which he belonged. He and a couple thousand other Cherokees left soon after for Indian Territory. The majority of Cherokees, however, led by Principal Chief (similar to a President) John Ross, who was 7/8 Scot and 1/8 Cherokee, opposed the New Echota Treaty and the relocation. They remained in their homeland until the U.S. army forcibly uprooted them a couple of years later. Broken promises by President Jackson and other Federal officials turned this phase of the Cherokees' westward relocation, in 1838-39, into the tragic Trail of Tears. The Cherokees called it, literally, "The Place Where We Cried." Thousands of them, mostly women and children, died in the vast open wilderness amidst a howling winter and sometimes brutal Federal soldiers, en route to their new homeland.

Once there, many of Ross's followers harbored bitter resentment against Watie and other leaders of what came to be known as the Treaty Party. Within six months of the larger Cherokee party arriving in Indian Territory, every Treaty Party leader except Watie was murdered. He escaped only by a comrade's warning, his own wits and courage, and the borrowed horse of white Presbyterian missionary friend Samuel Worcester. Years later, Watie and Ross and their two factions made peace, though their variant philosophies would flare again during the War Between the States.

GUERILLA AND GENERAL

A successful planter and journalist, Watie supported the Confederacy from its start. His influence helped lead the Cherokee nation into a formal alliance with the South. He and many fellow Cherokees, including William Penn Adair, John Drew, and Clem Rogers (father of famous American humorist and motion picture icon Will Rogers), as well as other Indians such as Seminole John Jumper and Creek G. W. Grayson, gained renown for their battle exploits – renown largely ignored in traditional American histories. The hard-riding Clem Rogers, for instance, was one of Watie's chief cavalry scouts.

Sarah Bell Watie

After fighting commenced in the (Indian) "Nations," Watie organized and commanded the Cherokee Mounted Rifles. These rough-hewn Oklahoma horse soldiers earned a fearsome reputation, far out of proportion to their numbers, for their accomplishments at such battles as Wilson's Creek in Missouri and Pea Ridge in Arkansas. At the latter, a subordinate recounted Watie's mounted Indian troopers, though outnumbered, charging into the face of blazing Federal cannon, capturing them, then turning them on their fleeing Federal enemy: "I don’t know how we did it but Watie gave the order, which he always led, and his men could follow him into the very jaws of death. The Indian Rebel Yell was given and we fought like tigers three to one. It must have been that mysterious power of Stand Watie that led us on to make the capture against such odds.”

Later, Watie's legend grew as a guerilla fighter while commanding Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Osage troops. One of his most famous exploits was the capture in a shootout on the Arkansas River of a Federal steamship and its $150,000 cargo. Another was his leading Confederate forces to victory in the Second Battle of Cabin Creek, in Indian Territory, where he captured an enormous Federal wagon train, the booty of which clothed his entire regiment and fed them and their civilian dependants for more than a month.

Tragically, the war forced Watie to fight not only Federal troops, who also included Indians, but some of his own people as well. The majority of the John Ross faction transferred their allegiance to the North when events turned against the Confederacy, and after Ross was captured by the Federals. Watie's own wife and children had to refugee from northeastern Oklahoma down the Texas Road into North Texas in the cold of winter and live out the war amongst the elements.

Year after year, Federal armies from all over the west hunted Watie. They never caught him. Brigadier General and Cherokee Chief Stand Watie fought to the bitter end. He was the last Confederate general to surrender, undaunted and unvanquished, on June 23, 1865, nearly three months after Appomattox.

SACRIFICE AND REMEMBRANCE

Watie returned to financial ruin and a home burned to the ground by Federals during the war. He spent his final years farming and trying to restore his once-beautiful Grand River bottomland, which was devastated by the war. Aging into his mid-sixties, Watie exhausted his war-punished body by committing every talent and meager resource remaining to him to the quality education of his children. Realizing this, one of his daughters, Watica, who had barely learned to read and write during a childhood savaged by the years of total war in the Indian Territory, wrote him from the private school to which he had managed to send her: "I feel proud to think that I have a papa that take the last dollars he has to send me chool."

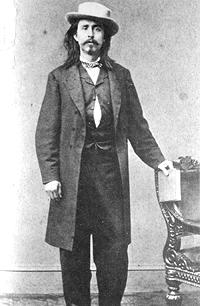

William Penn Adair (ancestor of modern-day Oklahoma House Speaker Larry Adair)

William Penn Adair (ancestor of modern-day Oklahoma House Speaker Larry Adair)

Tragedy continued to mark Watie's life as his beloved son Saladin – captain, decorated war hero, postwar Southern Cherokee delegate to Congress, and only twenty-one years of age – became the final of his three boys to precede him in death. He also watched as colossal tracts of land legally deeded to the Indians a generation before by the U.S. government, were taken from them as punishment for their support of the Confederacy and given to other tribes; as other vast tracts were confiscated from them and given to the mercantilist railroads racing westward; and as Congress began to levy taxes on Indian Territory business enterprises, while gradually eradicating the Nations' legally-sanctioned political independence. Tragedy has marked much of the American Indian's history since then as well, with one of their chief contemporary distinctions being that of helming the largest casino efforts in Oklahoma.

"You cant imagine how lonely I am up here at our old place without any of my dear children being with me," Watie wrote another daughter, Jacqueline, only weeks before his death in 1871. "I would be so happy to have you here, but you must go to school."

Like another fabled Confederate general, Robert E. Lee of Virginia, it was said that Chief Stand Watie died at least partly of a broken heart. Yet Mrs. A. K. Hardcastle wrote to Watie's widow, the lovely Sarah Bell of Tennessee: "I read with sadness of the death of your much esteemed husband. My tenderest sympathy is yours. I trust you have consolation from a Higher Power than earthly friends for the loss of one so dear to you. His labors on earth have not been in vain, he has done much lasting good for his country and country-men, that will never be forgotten but handed down to the future generations in the book of history for them to follow in his foot-steps and to aspire to leave their foot prints on the sands of time as well as he."

Indeed, he was not always forgotten. Edward Everett Dale, the great 20th-century University of Oklahoma historian, for whom that school's Dale Tower was named, remains long after his own passing, perhaps the dean of all Sooner State historians. Dale wrote many memorable books, among them Cherokee Cavaliers, which chronicled forty years of 19th-century Cherokee history, including the Trail of Tears, and which remains in print nearly seventy years after its writing. He filled the grand work with over 200 letters written by Cherokee men and women of the time, great and small alike. But he wrote his inscription to one: "To the memory of General Stand Watie – Patriot, Soldier, and Statesman – this volume is reverently dedicated."

Indeed, he was not always forgotten. Edward Everett Dale, the great 20th-century University of Oklahoma historian, for whom that school's Dale Tower was named, remains long after his own passing, perhaps the dean of all Sooner State historians. Dale wrote many memorable books, among them Cherokee Cavaliers, which chronicled forty years of 19th-century Cherokee history, including the Trail of Tears, and which remains in print nearly seventy years after its writing. He filled the grand work with over 200 letters written by Cherokee men and women of the time, great and small alike. But he wrote his inscription to one: "To the memory of General Stand Watie – Patriot, Soldier, and Statesman – this volume is reverently dedicated."

And this modest article.

February 23, 2006

John J. Dwyer (send him mail) is chairman of history at Coram Deo Academy near Dallas, Texas. He is author of the new historical narrative The War Between the States: America's Uncivil War. His website includes a five-minute preview video about the book. He is also the author of the historical novels Stonewall and Robert E. Lee, and the former editor and publisher of The Dallas/Fort Worth Heritage newspaper.