Having been recently appointed Anti-Money Laundering Officer at my investment firm, I now have the official, government-sanctioned power to scrutinize our clients’ account activity and report almost anything I deem “suspicious activity” to the federal government. Be worried, friends – be very worried – since every bank, every brokerage house, every financial institution in the U.S. is required by the Patriot Act to appoint an AML Officer, enact procedures to combat money-laundering, and file Suspicious Activity Reports on U.S. citizens. (You can view the 4-page SAR-SF form here.)

Having been recently appointed Anti-Money Laundering Officer at my investment firm, I now have the official, government-sanctioned power to scrutinize our clients’ account activity and report almost anything I deem “suspicious activity” to the federal government. Be worried, friends – be very worried – since every bank, every brokerage house, every financial institution in the U.S. is required by the Patriot Act to appoint an AML Officer, enact procedures to combat money-laundering, and file Suspicious Activity Reports on U.S. citizens. (You can view the 4-page SAR-SF form here.)

The Act’s definition of a financial institution is disturbingly broad. It includes dealers in precious metals, stones, or jewels; pawnbrokers; loan or finance companies; insurance companies; travel agencies; telegraph companies; sellers of vehicles, including automobiles, airplanes, and boats. Essentially, it means your financial transactions are subject to investigation if you purchase an engagement ring, insure your home, take a vacation or buy a car.

According to the statute, if I simply should have become aware of suspicious activity and fail to report it, I may have broken the law. So, if I have a head cold one day and miss a $5,000 wire transfer on a client’s brokerage statement – which is clearly suspicious activity since this client is a 90-year-old widow living on fixed-income investments, who has never made a wire transfer in ten years – I could be in trouble. (Don’t laugh – this applies not just to the AML Officer, but to every employee in a financial organization in a position to view client transactions. So, if you make an unusually large deposit at the bank one day, your teller must report this potential “suspicious activity” to higher ups or face possible sanctions.)

As AML Officer, I am required to report a client’s activity as suspicious if it merely fails to make business sense or appears to be without economic purpose. So, if a client transfers $10,000 into his investment account and breathlessly says “Buy gold stocks!” an hour after Alan Greenspan and Fox News proclaim “Scientists Prove All Gold on Earth is Iron Pyrite,” I have to turn him in.

If a client is a young school teacher and deposits, say, five $2,000 checks over a period of ten days, she must be questioned about it. Since this might be perfectly normal for a middle-aged, high-income surgeon, however, I wouldn’t have to question her at all – thus lower-income clients will necessarily suffer more intrusions into their privacy than those who earn more. By the way, as AML Officer I’m safe-harbored against violations of privacy laws I may be forced to commit while adhering to the regulations of the Patriot Act.

It gets worse. As I’ve noted, clients are to be questioned – and then reported to the feds on Form SAR-SF if I don’t like their answers – if their transactions indicate suspicious activity. But it does not end there – I’m also required to be on the lookout for potential tax evasion (as well as check fraud, embezzlement, theft, identity theft or mail fraud). So, if a client deposits $1,000 which he states he won by betting $1,000 on the Super Bowl, and wants to buy his daughter a Treasury bond with that money, I’m obligated by federal law to rat him out. Of course, all of this is just the tip of the Patriot Act iceberg; see, e.g., “Outside View: Patriot Act Problems.”

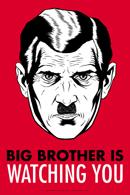

I find this situation repulsive in the extreme. It is Orwell’s 1984, slightly delayed. It will result in a paranoia explosion reminiscent of Nazi-era Germany. What if the Super Bowl bettor in the above example later hears from another person that I will probably file an SAR-SF about his $1,000 deposit? Will he then, out of fear, report it on his tax return – the government’s secondary desired end? Or will he just phone me and say he made “that betting thing” up? Then what do I do? Will he contact me and beg or threaten me to keep silent? Then what do I do? What if the bettor is my own father? Then what do I do!?

I find this situation repulsive in the extreme. It is Orwell’s 1984, slightly delayed. It will result in a paranoia explosion reminiscent of Nazi-era Germany. What if the Super Bowl bettor in the above example later hears from another person that I will probably file an SAR-SF about his $1,000 deposit? Will he then, out of fear, report it on his tax return – the government’s secondary desired end? Or will he just phone me and say he made “that betting thing” up? Then what do I do? Will he contact me and beg or threaten me to keep silent? Then what do I do? What if the bettor is my own father? Then what do I do!?

I’m already an unpaid tax collector for the federal government, since I prepare my firm’s payroll, and now, without my consent, I’m also its unpaid law enforcement agent and informant. I can only wonder, fearfully, what comes next.

August 6, 2005

Andrew S. Fischer has worked in various fields.