It’s hard to remember when media wasn’t dominated by political correctness. Television has always been politically correct because its real impact on the public didn’t begin until the late-1950s, a time when the civil rights movement was becoming the focus of the nation’s attention. Political correctness was a by-product of the civil rights movement and it began to infect media. Now political correctness controls television programming which is unfortunate because television is the primary "history" source for most people.

It’s hard to remember when media wasn’t dominated by political correctness. Television has always been politically correct because its real impact on the public didn’t begin until the late-1950s, a time when the civil rights movement was becoming the focus of the nation’s attention. Political correctness was a by-product of the civil rights movement and it began to infect media. Now political correctness controls television programming which is unfortunate because television is the primary "history" source for most people.

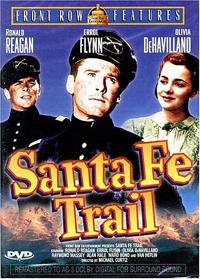

We have to go back prior to 1950 to find a real contrast to political correctness in media. Such a contrast can be found in some Hollywood films (the ones that haven’t been banned) because prior to political correctness the motion picture industry felt freer to present both sides of a story. One of the touchiest issues for the movies to deal with has always been slavery, but pre-1950 Hollywood films often attempted to present different perspectives on the subject, an illustration being Santa Fe Trail, a film originally released in 1940.

The title of this movie is misleading because it leads one to anticipate a typical Hollywood western adventure complete with cowboys, cattle rustlers and Indians. But Santa Fe Trail is not a "western" and the only reason I can think of for the title is that most of the action takes place around the Missouri/Kansas border where the Santa Fe Trail began its trek westward.

The film is set in the 1850s, and concerns the U.S. government’s attempts to capture the fanatical abolitionist John Brown, thereby putting an end to his violent attacks on unarmed citizens. And Santa Fe Trail is a fairly factual account the John Brown saga if you will allow some leeway for inconsequential "Hollywoodisms."

The story begins with the graduating class at West Point, primarily future generals, who, although friends as cadets, would later oppose each other in the War Between the States. The principal characters are J.E.B. Stuart (Errol Flynn), George Pickett, Philip Sheridan, John Bell Hood, George Custer (Ronald Reagan), James Longstreet, Robert Holiday (fictional) and Carl Rader (fictional.)

A little research will show that not all of these men attended West Point at the same time, but by placing them in the same class, screenwriters were able to develop the theme that the coming war, sparked by John Brown, would not only divide the nation but would also pit friend against friend and brother against brother.

The film begins with the West Point graduation ceremony for the cadets; the commencement speaker being Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War for President Franklin Pierce. (Erville Alderson, the actor who plays Davis bears a striking resemblance to the famous Confederate leader.) After graduation, Colonel Robert E. Lee, Superintendent of West Point, orders the new soldiers to the Kansas territory, to help keep the peace. Because the recent Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed territories to decide the slavery issue for themselves, pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in Kansas and Missouri were in constant conflict with each other. It was into this hostile environment that John Brown brought his followers.

John Brown (Raymond Massey) is an over-zealous abolitionist who professes to hear voices from God telling him that slavery must be ended immediately by whatever means, including bloodshed. Brown and his raiders wreak havoc on towns in pro-slavery areas, murdering those who, although they may not own slaves, support the right of others to do so. One of Brown’s sons, after being captured, confesses that he can no longer condone his father’s killings of others who do not share his fanatical views. He describes an event wherein his father slaughtered pro-slavery men with a sword while they were on their knees begging for mercy. (Actually Brown hacked the men to death with a machete as their horrified wives and children looked on.)

This film raises one of the crucial sociopolitical questions of the 1850s. The question is not whether slavery should end but how best to end it. As the film was made prior to political correctness, Hollywood was able to present the actual opinions that existed in the 1850s. Speaking for the South, J.E.B. Stuart argues that the region should be allowed to end slavery in its own way and in its own time. This was also the view held by President Franklin Pierce (1853—1857) and his successor, President James Buchanan (1857—1861).

On the other hand, John Brown and his abolitionist followers demand that slavery be ended immediately even if violence and bloodshed are required. Brown is furious at the President and Congress for not agreeing with him. In a confrontation with Stuart, whom he has captured, Brown presses his views on immediate emancipation. Stuart points out that Virginia is considering a resolution to outlaw slavery and that other southern states will follow Virginia’s example. All they ask is time. At this Brown explodes. "Time! I’ve been waiting 30 years for the South to cleanse its soul of its crimes!" Now, he claims, both sides must be brought into armed conflict and blood must be shed to end slavery.

This argument is first raised early in the film while the cadets are still at West Point. Cadet Rader, a follower of John Brown, distributes and reads aloud from inflammatory pamphlets written by Brown. Angered by what he considers an insult to the South, Stuart informs Rader that the South understands the problem better than John Brown does and it will settle it in its own way. The argument becomes heated and Rader reveals an intense contempt for Southern aristocracy which he refers to as "southern snobs" and "Mason-Dixon plutocrats" who amassed fortunes from slave labor. (He doesn’t mention the fortunes amassed by New England slave traders.) He then states: "The time is coming when the rest of us are going to wipe you and your kind off of the face of the earth."

A very telling scene occurs when Brown announces to a group of escaped slaves in his keeping that he is leaving them to continue his work elsewhere. He tells the slaves that they are now free. But the slaves are skeptical and one asks Brown: "Does just saying so make us free? How are we going to live? Get food and shelter?" This is one of the practical considerations that ivory tower abolitionists failed to address. In typical abolitionist fashion, Brown tells the slaves to find other people to help them and dismisses their concern with: "From now on you must fend for yourselves as other free men do."

Brown is finally captured by troops under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee at Harper’s Ferry Virginia. The film ends with the West Pointers and others witnessing the hanging of John Brown. They are grim-faced as if they realize that the small fires set by Brown might soon become an out of control conflagration. Brown was hanged in December 1859 and less than a year later Abraham Lincoln was elected President. Lincoln rejected the compromises with the South pursued by his predecessors, Pierce and Buchanan, making a War Between the States inevitable.

Santa Fe Trail avoids taking sides regarding the best way to end slavery. It simply presents the arguments as they were in the 1850s. John Brown is portrayed as part madman and part martyr. J.E.B. Stuart, Jeff Davis and Robert E. Lee are portrayed in a favorable light. Today however, 65 years after the film’s release, media has effectively converted John Brown into a hero and Lee and Davis into villains.

The film’s refusal to place the sins of slavery solely on the South is infuriating to some of today’s politically correct types such as Walter Fields, a columnist for "The Black Commentator." Fields writes that Santa Fe Trail "is a masterful piece of propaganda that sets out to make Brown a madman reining havoc on innocent whites; a misguided militant whose defiance on the slavery question threatened to upset the accepted social order of Dixie."

Of one scene Fields states: "In one of the most racist scenes depicting the aftermath of Brown’s attack on a settlement in the Delaware Crossing in revenge for an attack upon his son, a tearful young white girl walks out of the charred ruins of her home clutching a white doll. No doubt, the injury to a symbol of whiteness would compel the men in the settlement to declare their intention to bring Brown to justice." To claim that the film’s depiction of a young white girl in the 1850s, clutching a white doll is racist is a little bizarre and an indication of how far political correctness has gone.

When you mull over the arguments regarding how to end slavery presented in Santa Fe Trail, you are left with the disturbing realization that the War Between the States should have been avoided. Throughout the South there was a growing awareness that the institution of slavery could not be sustained much longer. Emancipation could have been accomplished peacefully as it was where it existed everywhere else in the west.

But major cultural and economic changes are not made peacefully without compromises.

President Lincoln’s refusal to compromise, refusing to even recognize the Confederacy or meet with its representatives, turned out to be a political miscalculation with tragic consequences. During the war, 620,000 soldiers were killed in combat. But this statistic tells only part of the story. Accidents, sickness, executions, outright murder and even suicide, boosts the number of the dead to between 1,000,000 and 1,500,000. Tens of thousands were severely wounded and disabled for the rest of their lives. Large sections of the country, especially in the South, were physically devastated. An official estimate of the cost of the war is $ 6,190,000,000. And all this could have been avoided.

Santa Fe Trail was directed by one of Hollywood’s finest directors, the late Michael Curtiz. This autocratic Hungarian ruled with an iron hand and has numerous great films to his credit including Mildred Pierce, White Christmas, Yankee Doodle Dandy and Casablanca. Santa Fe Trail was the third film where he matched Errol Flynn with Olivia de Havilland. He first cast the two in the 1935 film of Rafael Sabatini’s excellent swashbuckling sea story, Captain Blood and next in the classic The Adventures of Robin Hood.

In Santa Fe Trail, Flynn (Stuart) and Reagan (Custer) vie for the attentions of de Havilland, who plays the sister of Robert Holiday, one of the cadets. She is given the improbable name of Kit Carson Holiday. Of course, we know that Flynn (Stuart) will get the girl but, in order to have a happy ending, Kit Carson Holiday arranges a match between Custer and the daughter of Jefferson Davis. (Only a Hollywood screenwriter could dream up a match between Union General Custer and Jeff Davis’ daughter.) Playing the fictional Charlotte Davis is a perky blonde named Susan Peters, who was later paralyzed in an accident and died tragically at age 31.