Bread is one of the main sources of food in Germany, as it is in most other cultures. I always look forward to going home and eating our bread. It’s crunchy and solid, and has a texture that’s hearty.

Bread is one of the main sources of food in Germany, as it is in most other cultures. I always look forward to going home and eating our bread. It’s crunchy and solid, and has a texture that’s hearty.

The basic bread has a sourdough taste, with a touch of caraway. At times the caraway seeds are sprinkled on top of the loaf. Bread can have the form of a loaf or is round. The type of bread baked depends on the region of the country and can have a variety of flavors. Either way, taking a bite into a slice of fresh bread with real butter is hauntingly delicious leaving behind a satisfying feeling in my stomach and a fulfillment in my soul. Ask any German living in a foreign country, and they will tell you the same thing about our bread. They understand the craving for real bread!

I know all about making bread, since my grandfather was a baker in our small village in Franconia. I was literarily born into it the first year of my life, and at the age of six my family lived with my grandparents for two years on their farm as well. I also spent many summer months there during my school vacations.

I know all about making bread, since my grandfather was a baker in our small village in Franconia. I was literarily born into it the first year of my life, and at the age of six my family lived with my grandparents for two years on their farm as well. I also spent many summer months there during my school vacations.

Since the day I was born the bakery was a central part of my growing-up years. I played between sacks of flours, wooden bread pans, and baskets or watched my grandfather make the dough in a machine. He wore a white apron and white hat, and rolled the dough into shapes on a big hallow, wooden table that contained the flour. The best part was watching my grandfather shove the bread into the oven on big, long wooden u2018paddles.’ He’d sprinkle water on top of the bread and place it back into the oven. The smell of fresh bread still captures that part of my memory.

Since my grandfather was a master baker, he also had several fellows over the years that would help him out. Both of my uncles became bakers but did their apprenticeship in other bakeries. They no longer practice this profession, but still can bake some great bread and cakes.

Since my grandfather was a master baker, he also had several fellows over the years that would help him out. Both of my uncles became bakers but did their apprenticeship in other bakeries. They no longer practice this profession, but still can bake some great bread and cakes.

My grandfather sold his goods in a tiny shop at the front of the house. It had a small counter over which he sold the bread. Behind it were wooden shelves on both sides for the bread and a display with several glass bowls containing candy which he sold in brown triangle bags. I sometimes played back there and pretended to be a shop owner. When I was a teenager and spent my vacations there, I’d decorate the shelves with doilies and flowers. I even used to decorate the window and my grandfather just rolled his eyes, and walked off scratching his head in disbelief at what I did to his humble shop. I knew he wasn’t mad, because he always smiled when he saw the seriousness with which I went about my business.

When a customer entered the little shop the door rang a little bell. As a little girl I loved running out into the shop to see who it was. I knew everybody and liked to visit with the people that came in for their bread. Of course the flour dust all over my face and clothes gave some people a few laughs and they commented about my bakery look.

There was an older girl across the street from us whose family owned the only grocery store in town. She gave me the nickname of "Little Crumb" because I was the offshoot from a baker. Every time when one of the rolls she bought from my grandfather had an air pocket, she teasingly said that’s where I spent the night. Yes, I dreamed my nights away inside a bread roll. Still, the name stuck and to this day she calls me "Little Crumb."

The fashion of getting bread on the table was a natural cycle of continued events that involved the entire community of our little village and starts in the fall.

All the farmers went out into the field to plough the soil. Some still used horses and oxen. My grandfather had a small tractor. I always wondered how hard it must have been to plough without a tractor. It can take an entire day for a small plot of land.

All the farmers went out into the field to plough the soil. Some still used horses and oxen. My grandfather had a small tractor. I always wondered how hard it must have been to plough without a tractor. It can take an entire day for a small plot of land.

After the different grains and rye seeds were planted in rows it was left alone during the winter months. We always were glad for the snow, since the cover of the snow protected the sod from the cold. I heard the farmers talk amongst each other many times, and the main concern was always the planting, the weather, the harvest and where to get wood for the winter.

In the early spring, I could see the first sprouts coming through the ground. Most of the women were out in the fields with their colorful aprons and scarves, hoeing the ground of their potato and sugar beet fields. As a teenager I had to go out into the vineyard with the entire family and hoe.

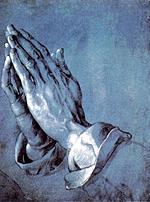

I know the blistering truth about hoeing. Wear gloves! One bends over constantly with a hoe in hand cracking the soil and pulling weeds. I’ve seen the hands of the older women; and I have the deepest respect for their hands. Albrecht Duerer’s famous praying hands are a tribute to these men and women that labor with their hands. He made these hands in honor of his brother who worked hard, so Albrecht Duerer could go to school and study his craft. No lotion in the world could remove the marks of their labor.

I know the blistering truth about hoeing. Wear gloves! One bends over constantly with a hoe in hand cracking the soil and pulling weeds. I’ve seen the hands of the older women; and I have the deepest respect for their hands. Albrecht Duerer’s famous praying hands are a tribute to these men and women that labor with their hands. He made these hands in honor of his brother who worked hard, so Albrecht Duerer could go to school and study his craft. No lotion in the world could remove the marks of their labor.

During the spring and early summer months the grain was green and growing strong. When the wind blew through the fields, the stems were dancing to the motion of the wind and I got saddened when a storm blew in and flattened some of the crops. Yes, life for a farmer was always under the mercy of nature herself. Their livelihood depended on it.

And then the harvest season started in late August. It was such a busy time of the year, because the time had to be used wisely. My grandfather also planted potatoes, sugar beets, and sunflowers. The crop had to be brought home and stored or taken off to be sold. We also needed hay for the cows, and several meadows had to be mowed, the grass turned over to be dried, and after another few days brought home.

And then the harvest season started in late August. It was such a busy time of the year, because the time had to be used wisely. My grandfather also planted potatoes, sugar beets, and sunflowers. The crop had to be brought home and stored or taken off to be sold. We also needed hay for the cows, and several meadows had to be mowed, the grass turned over to be dried, and after another few days brought home.

When we were children, this was a great time. The smell of fresh hay is better than the most expensive perfume. It smells sweet and, when you think about it, contains all the fragrant flowers that grow during the summer.

Trying to load it up on a wagon when we were kids was a trial in itself. It kept falling back down and all over us. Finally my parents and grandparents had a load filled and we were riding home on top of the hay wagon. This experience was the closest I’ve gotten to an amusement park ride. The only difference was that we came off the ride with grass and hay all over ourselves and smelling like it, too.

The most challenging job was the grain crop. Not everyone had a threshing machine, and the farmers that did sold their services to the others. Sometimes farmers from other villages would come in, too, to help out for a price. The plan how to handle the timing of it was most likely hatched out during Frhschoppen at the local tavern after Sunday church.

I used to go out with my grandparents for the grain crop. I watched the machine cut the stems that have turned golden by now, separating the grain from the stem and spitting out the remaining straw in a compact package at the rear. In the olden days it was a lot harder. My mother said they used steam engines and the straw had to be tied together by hand. Walking through the stubs left in the ground was very painful to the ankles. All of the children and adults had the marks of these stubbles with bloody scratches on our legs.

I used to go out with my grandparents for the grain crop. I watched the machine cut the stems that have turned golden by now, separating the grain from the stem and spitting out the remaining straw in a compact package at the rear. In the olden days it was a lot harder. My mother said they used steam engines and the straw had to be tied together by hand. Walking through the stubs left in the ground was very painful to the ankles. All of the children and adults had the marks of these stubbles with bloody scratches on our legs.

The hard labor required food and drink, and we waited for the church bell in the village to strike the hour of noon. My grandmother would then find a shady tree and we all gathered around her like hungry cubs. She pulled her leather satchel out that she kept with her at all times, and we had rolls, bread and lemonade. It doesn’t sound like much, but it was delicious and tasted wonderful after being outside working and running around in the heat. The bread was chewy and satisfying and filled us up until we went home.

We never said much when we ate. We just sat there and listened to the birds, and the breeze blowing through the trees. There was always something to look at. Sometimes we saw a deer or a rabbit, or another farmer passed by. I lay there in the tall grass and if an apple tree was nearby, would grab a few for desert. Cherry trees were around, too, and I’ve climbed in them several times in secret to find a spot in a branch just to eat a few of them. The only rule was; don’t get caught, and if caught, run!

Once the grain is taken back in brown cloth sacks, it was laid out to dry for several weeks and then taken to the local miller about 2 km away from the village near a small creek that had a water wheel. The grain was ground by two big sandstones that were turned through the power of the water wheel.

My grandfather had a business arrangement with all local and bordering farmers that for each five pounds of flour, the farmers would get six pounds of bread with a 90-Pfennig baker-wage. He would honor the deal by handing out bread-coins to the farmers bringing him flour to bake the bread and rolls for the community. When people came to buy a six-pound loaf of bread, they used their bread coins and only paid the baker-wage.

It seemed to work well, and this system worked for my grandfather until he finally retired in the early 1970’s. A similar system was in place with his father, grandfather and great-grandfather. He is the only one that came up with the coin idea to simplify the system. In the past they had markings in books for each contributor of flour.

The bread my grandfather baked was again the source of life for the people of the village. It was served for breakfast, lunch and supper. It tastes excellent with homemade sausage, pickles and tomatoes, as well as butter and jam. It was in our school lunches and in everybody’s leather satchel out in the fields.

Before slicing the bread my grandmother would bless the bread by carving a cross on the back of it with a knife. And only then was it allowed to cut the bread. My mother does it to this day. Bread is sacred and was acknowledged as a blessing that came about through many sacrifices and hard labor.

Before slicing the bread my grandmother would bless the bread by carving a cross on the back of it with a knife. And only then was it allowed to cut the bread. My mother does it to this day. Bread is sacred and was acknowledged as a blessing that came about through many sacrifices and hard labor.

I would bless my bread, too, if it wasn’t in a plastic sack. However, I acknowledge its value as food through thankfulness each day during supper time with my kids.

About 30 years ago in a small village in Franconia there still was a different way of making bread and is now at the twilight of its existence. It involved everyone’s effort and work to reap the fruit of labor. Bread is a perishable but life-giving food. The process it took to get on the table became of value to everyone. A forgotten value today, because man has forgotten its wisdom.

"And give us our daily bread…" will always be a demand in our world. Learning how to share that value again will be our generation’s challenge.

"And give us our daily bread…" will always be a demand in our world. Learning how to share that value again will be our generation’s challenge.