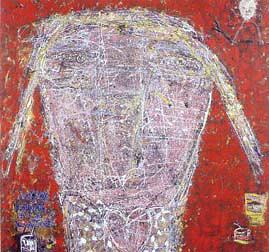

In the play ART, someone buys an abstract painting at an enormous price, while his friends ponder how they are going to tell him that it is inherently worthless. In the debate about abstraction and whether it was entirely some sort of hoax, the new traditionalists ridicule its "flatness" and its absence of narrative, while defenders of abstraction insist that representative art is a form of nostalgia that modernism sought to eliminate. The defenders are definitely losing ground, but one wonders why they were ever regarded as credible.

In the play ART, someone buys an abstract painting at an enormous price, while his friends ponder how they are going to tell him that it is inherently worthless. In the debate about abstraction and whether it was entirely some sort of hoax, the new traditionalists ridicule its "flatness" and its absence of narrative, while defenders of abstraction insist that representative art is a form of nostalgia that modernism sought to eliminate. The defenders are definitely losing ground, but one wonders why they were ever regarded as credible.

The point that most art critics miss is that art is also a form of commerce, and not antithetical to it. The god of art is the art market. And so one might ask, "How did a Jackson Pollock get to be worth so much money?" Part of it had to do with the Cold War, which not only bloated the military budget, but distorted the art market as well.

Faux genius and con man Clement Greenberg was at the center of the scam. A former itinerant necktie salesman, Greenberg teamed up with struggling abstract artist and mountebank, Barnett Newman, to promote a vision of art that conveniently coincided with the objectives of the US Cold War Establishment. Indeed, Greenberg argued that the avant-garde required the support of America's elite classes, a self-serving concept that would promote his personal interests as a collector.

As the competing ideologies of capitalism and communism clashed after the Second World War, the question of "What is art?" became a significant issue in the struggle for dominance. Was art a vehicle of state propaganda to glorify a proletarian revolution or depict an evil Hitler in his bunker at the end of the heroic struggle against fascism (never mind about the Hitler-Stalin pact), or was it the product of individual creativity unrestrained by governmental control and censorship?

But since America was then in the throes of one of its tedious puritanical backlashes, the sensuality of great Western art, as represented by say, Goya's "Naked Maja," was out of the question. Deriving their central thesis from Islamic art that representation of the sensual human form was interdicted by the sublime, the new Abstract Expressionists fit neatly into what the American intelligence community desperately needed to rebut Soviet representational propaganda; an art that was highly individualistic but which did not offend the sensibilities of conservative religion. A Baptist preacher or Bishop Sheen could laugh at a Pollock, but he could not condemn it as obscene. Yet because "modern art" was widely derided, it needed a boost from an invisible sponsor, which would turn out to be the CIA.

In this milieu Clement Greenberg came forth in support of the new art. Yes, the canvas was flat, and it should be covered flatly by paint in abstraction, so beauty would be destroyed in the name of the sublime. And Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) director Richard Barr heralded this view when he quoted Greenberg's co-conspirator, Newman, who infamously proclaimed, "The impulse of modern art was to destroy beauty." Barr went even further – God was dead and had been replaced by Abstract Expressionism.

The more Greenberg wrote in promotion of the Abstract Expressionists, and particularly Pollock's "action painting," which involved dripping paint on the canvas, the more he collected them at minimal prices before he had made them famous. And as he increased his own power and influence, the more people wanted to buy these paintings, which served Greenberg's real personal objective; to make himself rich.

Fortunately for him, like the military industrial complex, he had a helping hand in the federal government. As Frances Stoner Saunders explains in her brilliant book, Who Paid the Piper – The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, the CIA covertly supported the Abstract Expressionist movement by funding exhibits all over the world in promotion of the idea that the culture of freedom was superior to the culture of slavery, and by covertly promoting the purchasing of works by various private collections. Indeed, the CIA named its biggest front in Europe the Congress for Cultural Freedom. It worked. Soviet art became a laughing stock, and New York became the center of the art world, not Paris, where Picasso, a long-time member of the Communist party and winner of the Stalin Peace Prize (who can forget his doves of peace?), still reigned supreme.

The CIA had stolen the show from Picasso, taking art a step further into a near mystical expression of unfettered human liberty in the spirit of free enterprise. Nelson Rockefeller, whose family created the MoMA, actually referred to Abstract Expressionism as "free enterprise painting." But like so many Rockefeller ventures, it was state supported, so that his own collection of Abstract Expressionist works ended up being worth a considerable fortune.

But why, then, did it come to an end? The Cold War exploded into the Vietnam War and rebellion overtook the arts. The social revolution of the Sixties brought with it Pop Art, Op Art, and various forms of social protest art, forcing Abstract Expressionism to the sidelines, even if prices were still good. Confronted with James Rosenquist's "F-111," abstraction lost its force. Even more than this, the answer lies in a paraphrasing of a remark by comedian Mort Sahl about why the student movement ended. "The government withdrew its funding."

June 20, 2002

Richard Cummings [send him mail] has taught at the University of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the University of the West Indies, Barbados, and St. Catherine's College Cambridge. He holds the PhD in Social and Political Sciences from Cambridge University and “completed with distinction” the 21st Session at Cornell University, of The School of Criticism and Theory. He is the author of the comedy, “Soccer Moms From Hell” (recently produced in New York) and the forthcoming novel, The Immortalists.