This review originally appeared in the Libertarian Forum, July-August 1984.

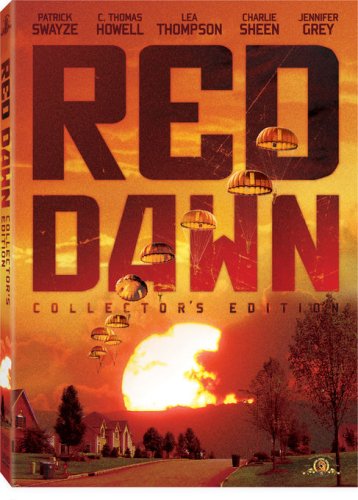

Red Dawn, directed by John Milius.

It’s not only the Supreme Court that follows the election returns. Hollywood, too, does its bit, and movie theatres have been increasingly filled with right-wingy patriotism, like the rest of the media this endless summer. I went to see Red Dawn expecting a bout of anti-Soviet warmongering, but instead was pleasantly surprised. This is hardly a great picture, and is indeed flawed. But Red Dawn is an enjoyable teen-age saga, and, apart from right-wingy pro-NATO credits at the beginning of the film, it is not so much pro-war as it is anti-State. The warfare it celebrates is not interstate strife, but guerrilla conflict that the great radical libertarian military analyst, General Charles Lee, labeled “people’s war” two centuries before Mao and Che.

The beginning of the picture is exciting, if idiotic. Cuban, Nicaraguan, Mexican and other Commie Hispanic troops, headed by Soviet advisors, parachute into and successfully conquer the entire prairie Mid West, from the Rockies to the Mississippi. In the opening sequence, the Red paratroops swiftly invade and, for some reason, annihilate a high school in the mythical town of “Culver City,” Colorado, presumably somewhere in the East Slope foothills of the Rockies. In a neat touch, gun control has made it easy for the Commie occupiers to round up all the registered guns in the area. But a half-dozen high school kids escape and set up a guerrilla camp in the Rockies. Jed, the older leader and a former school quarterback, whips the other reluctant lads into shape, and soon the tiny guerrilla band, using light arms, mobile tactics, and superior knowledge of the terrain, strike terror into the Red occupying forces while brandishing the rallying name of “Wolverines.” There are some revoltingly macho touches at the beginning, especially when one of the young lads receives his mystical baptism into the guerrilla rites by drinking the blood of his first kill – fortunately a deer rather than a Commie. These touches subside after a while, although they are hardly softened by the appearance of two young lady guerrillas who are fierce and androgynous enough to pose for a Viet Cong or Algerian guerrilla poster.

Red Dawn (Collector&rs...

Best Price: $1.52

Buy New $8.15

(as of 11:36 UTC - Details)

Red Dawn (Collector&rs...

Best Price: $1.52

Buy New $8.15

(as of 11:36 UTC - Details)

One of the best parts of the picture is the graphic portrayal of how the Red response to the Wolverines runs the gamut of the U. S. counter-revolutionary responses to the Vietnamese. That is, at first the Russian commander decides to hole up in the cities and military bases, into the “safe zones,” whereupon the Wolverines boldly demonstrate that in guerrilla war there are no safe zones, and that the “front is everywhere.” At that point, another crackerjack Russian commander takes over, and replicates the “search and destroy” counter-guerrilla response of the Green Berets. This is more punishing, but still does not succeed.

One big problem with the picture is that there is no sense that successful guerrilla war feeds on itself; in real life the ranks of the guerrillas would start to swell, and this would defeat the search-and-destroy concept. In Red Dawn, on the other hand, there are only the same half-dozen teenagers, and the inevitable attrition makes the struggle seem hopeless when it need not be.

Another problem is that there is no character development through action, so that, except for the leader, all the high school kids seem indistinguishable. As a result, there is no impulse to mourn as each one falls by the wayside.

But whatever flaws the movie has are redeemed by one glorious – and profoundly libertarian – moment. The Nicaraguan-Cuban insurgent leader is increasingly unhappy acting as a State occupying force. He tells the implacable Russian commander: “Once I was an insurgent. Now I’m a policeman” – the last word spoken with profound contempt. He writes his wife: “What am I doing in this cold and lonely spot, so far away from home?” So that, in the climax of the film, as one people’s war guerrilla to another, he saves the hero, Jed, and allows him to slip out of the Russian net. Ideology, left and right, gets swallowed up in hands-across-the-sea of people’s guerrillas against their respective States.

But whatever flaws the movie has are redeemed by one glorious – and profoundly libertarian – moment. The Nicaraguan-Cuban insurgent leader is increasingly unhappy acting as a State occupying force. He tells the implacable Russian commander: “Once I was an insurgent. Now I’m a policeman” – the last word spoken with profound contempt. He writes his wife: “What am I doing in this cold and lonely spot, so far away from home?” So that, in the climax of the film, as one people’s war guerrilla to another, he saves the hero, Jed, and allows him to slip out of the Russian net. Ideology, left and right, gets swallowed up in hands-across-the-sea of people’s guerrillas against their respective States.

In all war pictures there is the annoying pacifist nudge, griping about “how do we differ from them,” since both are shooting and killing. (The LeFevre-Smith motif.) Jed’s answer is satisfactory enough, even though lacking profound argumentation: “Because we live here!”

Another fine touch is that the evil informer who almost does the Wolverines in is, naturally, the son of the town Mayor, who is identified by friend and foe alike as “the politician.” The Mayor, who directs the betrayal, cringes fawningly if despairingly in carrying out the orders of the occupation force.

All in all worth seeing – exciting as well as libertarian.

Reprinted from Mises.org.