Recently by Bill Bergman: Examining the Myth of Good Government and the Coming Fiscal Collapse

Some recent and not-so-recent news items help reinforce the arguments for broader audits of the Federal Reserve.

The Government Accountability Office recently issued two special audit reports relating to the Fed's activities leading up to and amidst the recent financial and economic crisis. The reports from those audits outlined the breathtaking scope of the Fed's bailout (u201Crescueu201D?), and also described some of the conflicts of interest arising within the Fed while pursuing those efforts. But these audits were constrained by the law that required them (Dodd-Frank).

A congressional effort remains underway to broaden the scope and deepen the authority of Congressional oversight of the Fed. This effort is resisted by defenders within and attached to the Fed, with some of their most important arguments rooted in concern that the Fed's operations should retain their u2018independence' from murky political forces.

Three interesting but little-discussed topics related to Fed independence matter for the effort to develop a more strenuous audit. They include a recent scolding of a large accounting firm, a curious Fed income statement line item, and some older information from visitor logs.

Peek-A-Boo!

When faced with demands for audits, the Fed and the public frequently have to deal with shrill but sometimes-uninformed complaints that u201Cthe Fed isn't audited.u201D The Federal Reserve Banks have internal auditors, and the Reserve Banks are also overseen by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, a government agency. The Federal Reserve Banks produce financial statements, and those financial statements are audited by independent accounting firms. And the Congress has directed the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to conduct special Fed audits in the past. The Fed frequently points to these facts in its defense.

But existing audit mechanisms could still be inadequate, particularly in light of special issues relating to the financial crisis, such as the prices paid for risky securities that the Fed has purchased in its open market operations in massive quantities recent years. The law currently puts monetary policy out-of-bounds for GAO audits, for example, and the GAO was so constrained in the most recent audit on this score as well.

And several weeks ago, a news item arose that undermined one of the defenses that the Fed uses to deflect demands for more forceful Congressional oversight and auditing.

The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (the PCAOB, sometimes referred to as PeekABoo) was created by law in 2002 in response to the Enron and related scandals. The PCAOB is directed to oversee the work of public accounting firms. The PCAOB issues standards, examines auditors, and pursues enforcement actions. In mid-October, the PCAOB released a previously-private portion of an inspection report of Deloitte Touche LLP, one of the largest accounting firms in the world – and the firm that audits the Federal Reserve Banks. The release of this previously-private portion of its inspection report indicated that the PCAOB found insufficient progress at Deloitte in addressing issues for which it was cited in previous years.

This development provides a reminder that u2018independent' audits may not always be so independent, and that one element of the control system over the Federal Reserve Banks might not have been all that it was advertised – during the worst financial and economic crisis since the Great Depression. The Deloitte citation supports the case for those calling for Congress to pass H.R. 459 and S. 202, the bills providing for broader audit authority.

One Item on the Fed's Financial Statements

The Washington D.C. economy has been in the news lately. It has proved remarkably resilient to the crisis that impacted the rest of the nation. The 12 Federal Reserve Banks may be Federal, although outside the Beltway. Their compensation and employment levels have also been very resilient to the recession. On the one hand, the Fed could argue that they have been doing a lot of hard work dealing with the financial mess, and this is a certainty. But there are some interesting arguments put forward, by Ed Kane and others, that we should reconsider compensation schemes and their incentives not only for u2018private' financial firms, but for financial regulators as well. Kane argues for better performance sensitivity in the compensation of regulators, including a downside if a crisis arises on their watch.

Putting the merits of that debate aside, a simple question arises. What has actually happened? How has the compensation of the Reserve Banks trended in recent years?

Well, based on the Fed's publicly reported (and u2018independently audited') statements, it isn't that easy to tell, at least on the surface.

The individual Reserve Banks all publish annual reports, including financial statements audited by the above-noted Deloitte and Touche LLP. Those statements are not prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), like public company statements, but by the Financial Accounting Manual developed by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. There are material differences between GAAP and these principles, including those for the valuations of securities on Reserve Bank balance sheets that raise questions relating to the demand for stronger audits of monetary policy operations.

But the u2018salaries and other benefits' line item on the Reserve Bank income statements poses some questions.

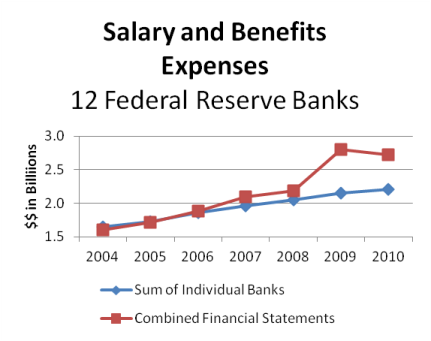

If you simply add up the totals for what the individual Reserve Banks report for their salaries and other benefits expense, you get a smooth, unbroken upward trend seen in the chart below. But if you use the salary and benefits expense line reported on the Combined Financial Statements for the Reserve Banks, you get another result – with much faster growth from 2008 to 2010, amidst the worst financial and economic crisis since the Great Depression.

There may be interesting and valid reasons why this discrepancy arises. One clue may lie in that these expenses are titled u201CSalaries and other benefitsu201D on the individual Reserve Bank statements, while they are called more simply u201CSalaries and benefitsu201D in the combined financial statements from the Board of Governors. But even if valid reasons for the discrepancy exist, other questions arise. The Federal Reserve banks individually report compensation results to their Boards of Directors, the Congress, and the public that appear significantly at odds with those the Board of Governors reports on the Combined Financial Statements. Compensation costs in the Reserve Banks have grown much more sharply under the aggregated measure. In fact, there are roughly $1 billion more compensation costs on the combined statement in 2009 and 2010. In either case, the Reserve Banks' compensation certainly didn't suffer like it did in much of America.

The Fed and its defenders regularly cite the need to keep monetary policy independent from politics as a bulwark from efforts in Congress and elsewhere for broader audit and oversight authority. But is the Fed itself really an apolitical creature? Special interest groups have a well-documented ability to u2018capture' regulatory agencies, and the Fed is certainly not immune to those political forces. But some questions about Fed independence might also arise in a more traditional, partisan context.

In 2004, the Washington Post published an article describing the work of Ken Thomas, then a lecturer at the Wharton School. Thomas sought and obtained records of visits to the White House by then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan. Thomas documented a sharp increase in the frequency of visits to the White House beginning in 2001 – the year of the new Republican Bush Administration. In a world with a nonpartisan, truly independent Fed, this is a curious if not compelling statistical discrepancy.

This mid-2004 article cited u2018at least' 17 meetings Greenspan had with Vice President Richard Cheney, 11 meetings with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, 12 meetings with National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice, six meetings with White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card, two meetings with Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, one meeting with Secretary of State Colin Powell, and one meeting with Cheney's chief of staff, Lewis u201CScooteru201D Libby. The article also noted that Greenspan met with George W. Bush once, but it wasn't with President Bush. It was about a month before he was inaugurated.

Was this in response to the events of September 11? The article also noted:

Greenspan had at least four official appointments with Cheney and one with Rumsfeld before the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, according to the Fed records.

Any future Fed audit could also include an audit of the sharp increase in currency shipments from Federal Reserve facilities, billions of dollars in $100 bills, in July and August of 2001 as well.

The recent release of two lengthy if constrained GAO Fed audit reports provided some grist for the mainstream news mill, and coupled with a steady drumbeat of other newsworthy financial events to take some of the air out of the balloon of the u201CAudit the Fedu201D movement. But the bills providing for wider audit authority have attracted a significant number of co-sponsors. In light of the worst economic and financial crisis since the Great Depression, the time still appears ripe for a thorough, honest review of the functioning of our central bank in recent years.

When the Fed and its defenders point to the possibility of Congress getting its grimy hands on what should be a nonpolitical process, they certainly find fertile soil among the millions of people fed up with our political representatives. But at the end of the day, the Fed is not only u2018nonpolitical,' it is a constitutional being, and a creature of our Congress. For all our cynicism, we would also note that we as citizens have done a poor job monitoring our risk exposure through the entities we have created. A thorough Fed audit from the Congress appears warranted.

Reprinted with permission from BoilingFrogsPost.com.

November 25, 2011

Bill Bergman [send him mail] is Senior Financial Analyst, “Follow the Money with Bergman” at Boiling Frogs Post. He has 10 years of experience as a stock market analyst sandwiched around 13 years as an economist and financial markets policy analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.