Ever wonder how that delicious, golden green elixir that adds so much flavour to your food got to your table? Olives have been cultivated in Greece for millennia and my family continues that tradition. My father comes from the south-eastern Peloponnese region of Greece known as Laconia prefecture. The capital is the legendary Sparta. Far from being the great military power it once was, today Sparta is mostly an agricultural center. Fortunately, instead of ferocious warriors, some of the best table olives and olive oil now come from there.

I just recently started an olive oil business and that requires my visiting Greece to check up on everything. Yes, it's a terrible burden (wink, wink). The olive-picking season begins in November (table olives, like the renowned, succulent Kalamata type) and continues until February for the oil olives; no they are not the same. My visit was in January. In Montreal, January is cold, cold, cold and while Greek winters are warmer, there's a bone chilling humidity even if the temperatures hover in the single digits (Celsius.) The days come with a mixed course: gray skies, rain, the sun teasingly peeking through and don't be surprised to see the occasional sprinkling of snow. In other words, if you don't like the weather, wait a few minutes and it'll change.

My arrival in the village started with food, a wonderful dinner of rooster, roasted in the fireplace. Themistocles, my cousin with whom I share the first name, mentioned that the next day we'd be off to pick olives. What he was really saying was that I was to be included in the crew. What? I came here to observe not to work. Besides, my soft, moisturized city-boy hands aren't up to this type of toil.

My arrival in the village started with food, a wonderful dinner of rooster, roasted in the fireplace. Themistocles, my cousin with whom I share the first name, mentioned that the next day we'd be off to pick olives. What he was really saying was that I was to be included in the crew. What? I came here to observe not to work. Besides, my soft, moisturized city-boy hands aren't up to this type of toil.

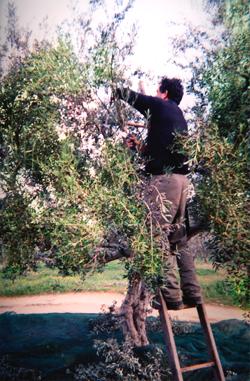

Olive picking is hard, labour intensive work, but the process is simple and not much changed from the ancients. We start by laying down tarps under a cluster of trees. Themistocles climbs up on a ladder and manually saws off selected branches, what he is really doing is pruning the tree and that requires a certain expertise to ensure the health of the tree and future production. Today, many are using electric saws, but hospital emergency rooms are full of bleeding farmers, so Themistocles sticks with the older, slower shoulder-aching method. I pick up the branches teaming with bunches of green and burgundy little olives, no bigger than a fingernail and pile them beside Magda, his wife. She is working at a machine with spinning rollers. The rollers have plastic fingers about 10 cm long and the spinning motion thrashes the branches causing the olives to fall below into a plate then into a woven sack. I don't know how she does it because it's requires a lot of strength and stamina, but she keeps going and going like the Energizer bunny. Meanwhile, Themistocles starts the next tree.

Of course, you can't cut off all the tree's limbs, some olives simply have to be picked. That's where Themistocles' son Spiro, comes in. He uses a special tool that looks like a broomstick with some bristles sticking out the sides at one end. The bristles are made of semi-hard plastic and an electric motor powers a back and forth motion that agitates the branches causing the olives to fall. This also requires a certain amount of skill so as not to damage the precious tree.

Once the tree has been completely pruned and picked and Magda has passed all the branches through the thrashing machine, we have to round up all the olives from the tarp. This is a simple enough task, but the tarp is also full of small branches and leaves. We lift up the edges of the tarp and accumulate the whole collection in one spot. With a rake we separate as many olives as possible, put the rest in a little pile which is spanked with a rubber hose to loosen any remaining fruit.

Once the tree has been completely pruned and picked and Magda has passed all the branches through the thrashing machine, we have to round up all the olives from the tarp. This is a simple enough task, but the tarp is also full of small branches and leaves. We lift up the edges of the tarp and accumulate the whole collection in one spot. With a rake we separate as many olives as possible, put the rest in a little pile which is spanked with a rubber hose to loosen any remaining fruit.

The heavy sacks filled with olives are fastened together with wire, put into the cart and we move on to the next collection of trees as the process continues. With three people on the job, on a good day, you can hope to do 10 trees. This goes on every day except Sunday. Never, never on a Sunday.

I was lucky because on my day the weather was good. It did rain, but just a little. You can expect rain and that raises the miserable factor to the task not to mention risking the tractor sinking into the wet soil. My father's generation would really work for their olive harvest. They would prune the trees and pick the olives by hand, no thrashing machinery, electric picking tool or tractor, just hands and donkeys. They were lucky if they could do more than two trees a day meaning most of their harvest was mostly for their own consumption with little left over to sell for money.

We sat down for a quick lunch and was I famished. Our country repast consisted of olives (surprised?), bread and for protein an omelet made with last night's leftover fried potatoes (surprisingly good) and some cheese. Dessert was as many delicious and juicy oranges as our hearts desired since they're in season. Then it was back to work.

The fields are full with frantic farmers hurriedly harvesting their livelihood and this also is a key reason why Greek olive oil is of a consistently high quality. There are many small family plots tended by the owners, therefore there's a little more tender loving care in the work; should you damage a tree, next year's yield may suffer. You want to be careful where you step, lest you crush the precious fruit. Greece is naturally blessed for growing superb olives: lots of warm sun, not too much rain and good soil. However, an olive starts to degrade quickly once picked and if it is not pressed soon, the benefits nature has supplied are wasted. There is also an economic incentive; if the olive oil produced is of middling quality, the farmer will earn less. Which brings us to the second part of olive oil production: extracting the oil.

Just like there are many small producers, there are many olive oil presses, known as lidrivio. Pretty much every village in the olive producing regions of Greece have at least one (often more than that) lidrivio. My father's village, Finiki (pop. 2500) has three. My cousin simply picks his olives and within 24 hours drives up with his tractor loaded with sacks of olives to have them pressed. Then he returns to the fields to continue the hard work. The process of extracting oil from the olive is relatively simple and even though this is the village, the technology is quite up to date.

The olives are placed in a pit where they pass through a blower that removes any remaining leaves and twigs. Then they are washed. They continue on to a "mulcher" with blades similar to those of a snowblower. The result is a tapenade that goes into a centrifuge. This spins at 3500rpm and removes the heavier bits: the pits and skin. Finally, the remainder passes through a second centrifuge which separates the oil from the juice. What's left is an unfiltered olive oil that is poured into barrels which are weighed. As you can see, there is no pressing involved anymore. Samples are taken to measure the acidity content and grade the quality. These will determine the amount paid to the producer. This olive oil is wholesaled to buyers from many other nations. The buyers take the unfiltered olive oil to their bottling plant where it is filtered, bottled, labeled and packed and shipped all over the world to be enjoyed as it has been for thousands of years.

The olives are placed in a pit where they pass through a blower that removes any remaining leaves and twigs. Then they are washed. They continue on to a "mulcher" with blades similar to those of a snowblower. The result is a tapenade that goes into a centrifuge. This spins at 3500rpm and removes the heavier bits: the pits and skin. Finally, the remainder passes through a second centrifuge which separates the oil from the juice. What's left is an unfiltered olive oil that is poured into barrels which are weighed. As you can see, there is no pressing involved anymore. Samples are taken to measure the acidity content and grade the quality. These will determine the amount paid to the producer. This olive oil is wholesaled to buyers from many other nations. The buyers take the unfiltered olive oil to their bottling plant where it is filtered, bottled, labeled and packed and shipped all over the world to be enjoyed as it has been for thousands of years.

There you have it. Don't be afraid to pour that delicious oil on all your food, it's not just for salads. I don't recommend drizzling it on ice cream, although I read somewhere that the Japanese make all kinds of original ice creams; maybe if I called…

December 29, 2005